Forty years after the American Revolution, one of its most beloved heroes arrived in the United States for his fourth and final visit. It was partly a triumphal tour and partly a sentimental journey, but most of all, the Marquis de Lafayette’s travels through every state of the Union (there were twenty-four at the time) reunited him with a dwindling cadre of old friends. Like him, they had grown old and frail, but Lafayette was a game traveler, and he soldiered through an itinerary that spanned more than a year and covered ground a young man would have found daunting. By that spring almost two centuries ago, he was well along on his trip. He had visited Thomas Jefferson at Monticello, had been fêted at the University of Virginia, and was extravagantly welcomed by Congress and President James Monroe in the nation’s capital. Everywhere enormous crowds turned out to cheer.

Why all the fuss over an old French guy whose service to his hosts had been nearly a half-century earlier? The answer is in recalling the lad not yet twenty who showed up when America was fighting for its life and asked for nothing more than a chance to help.

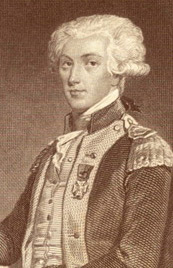

When George Washington first met the Marquis de Lafayette in August 1777 at a dinner party, he was mildly dismayed to be introduced to a mere child with a preposterous rank. Slim and self-conscious, Lafayette stood very erect and soldierly, possibly to augment his height (about 5’9”) while in the company of the towering Washington. Lafayette had reddish sandy hair, blue eyes, and a prominent slope to his forehead that gave the impression even at nineteen of a receding hairline.

Nothing could allay the impression that he was very young. Despite Lafayette’s youth, Congress had cited his “zeal, illustrious family and connexions” to make him a major-general. Washington could see only a major headache, another instance of politicians placating foreigners rather than sending him competent officers. He could only imagine the reaction of his staff, not to mention the line officers such as Nathanael Greene, who had started the war as a lowly private in a Rhode Island militia company.

Yet before the evening was done, Washington was confused. Lafayette had a charming modesty, a sort of clumsy eagerness, and a disarming desire to learn rather than lecture. As George Washington gradually came to know the boy born into noble rank and high privilege, someone from a world alien to everything the Virginia farmer had ever known, something extraordinary happened. If Lafayette as a toddler had padded along the halls of Mount Vernon, or had come bolting out of one of its stables spurring a young colt, or had pondered great questions while gazing across the Potomac from the mansion’s piazza, George Washington could not have known him better than he did by the end of that evening. Sparkling enthusiasm enlivened the kid, and the sincere admiration he openly displayed for everyone he met endeared him to them immediately. He made clear that he believed everybody in the impossible American project was a genuine hero, and for them, Lafayette ceased to be a foreigner; his world was not alien, his horrible English was not strange.

Washington invited him to visit headquarters the next day. He planned to introduce Lafayette around and take him on an inspection tour of Philadelphia’s batteries. The young man arrived early as if he’d been unable to sleep in his eagerness for the appointment. He was wearing a uniform he had purchased, a resplendent and colorful collation of braid and shiny buttons, which was a high contrast to the shabby ordinariness of Washington’s aides and the tattered condition of the army’s officers. As they gazed at the Continental Army’s rank and file in dirty linen hunting shirts, Washington mentioned that they must seem comical to someone familiar with the pomp and precision of European militaries. Lafayette was surprised. In broken and heavily accented English, he replied simply, “I’ve not come to teach but to learn.” Washington smiled.

His name was Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de Lafayette. The only son of a soldier descended from a long line of soldiers, Lafayette was only two-years-old when his father was killed in the Battle of Minden in 1759. His mother died after a brief illness eleven years later. The boy was wealthy, the inheritor of not just a title but of considerable estates and capital that gave him an annual income of 120,000 livres (about $2 million in today’s money) without his ever touching the principle. Other than money, nothing about him was particularly remarkable. He attended a military academy and received the education typical for martial nobility in France, which is to say, not very much in quality or quantity. Though still a child, he was shoved into an arranged marriage with a pleasant girl, also a child, so it is understandable that his home life was more cordial than passionate.

Lafayette was a bundle of passions, however, for philosophies that lauded liberty. It gave an already awkward youth a strangely serious side. He was so stilted at formal balls that Marie Antoinette and her ladies-in-waiting made him a figure of fun. He was bashful and often at a loss for words until an idea seized him, causing him to erupt into torrents of exclamations and flowery phrases. He was the sort of fellow who knocks over everyone’s wineglass when gesticulating during a story.

Lafayette had no military experience and owed his position as a garrison captain to his wife’s influential family, so by the time this kid arrived in Philadelphia, the flood of foreigners who’s boasts exceeded their talents had already poisoned the well, exhausting the patience of George Washington and much of Congress. Accordingly, the congressional committee in charge of recommending commissions treated Lafayette dismissively — his interview was conducted at the curbside outside Independence Hall — but he persisted, and along the way, something the nineteen-year-old said struck a chord. Lafayette had finally made clear that he was asking for only two things: he wanted to serve in the American army, and he did not want a penny for doing so. A stunned Congress made him a major-general. The tongue-tied kid often at a loss for words had found just the right ones. It was because he meant them. Lafayette never lied.

The commission he received was merely honorary, and Congress took him at his word about compensation. In only three months, however, Lafayette’s earnestness and sincerity earned Washington’s affection. A meaningful command soon followed. As the British moved on Philadelphia, Lafayette was helping rally stragglers at the Battle of Brandywine when a bullet tore into his leg. Washington told the surgeons to take care of the young man as if he were his son.

He never traded on Washington’s affection, and thus was Lafayette able to rise above the jealousies and suspicions that older officers trained on one another. Everyone liked him, and the discerning came to value his good opinion of them. In turn, he had a way of admiring people without fawning over them, displaying an innocent sincerity in everything. He adopted American customs, such as using his knife as a spoon and taking his turn to drink from a goblet as it was passed around.

Among Americans who fought for independence, Benedict Arnold profited the most, and that was by trying to sell it out. Lafayette, the ultimate contrast in purpose and person to Benedict Arnold, had the best estimate of the man. When the British put Arnold on general staff commanding a brigade, Lafayette casually observed, “There is no accounting for taste.” But the flippancy masked a profound quality in this young man.

Lafayette was more than the antithesis of Benedict Arnold. He was civic virtue personified, the kind of man who expected success, suppressed pessimism, and embraced glad tidings as the natural order of things. He had resolved to fight tyranny wherever he found it, first, last, always, forever, and he became a mirror for American soldiers who also had little or no experience as they leveled guns and stood their ground. All of them believed they had something better in the purity of good motives and the unyielding courage that comes with them. Armed with that, American victory was a triumph of will and virtue, a miracle against all odds, a gift from the hand of Providence to a deserving people. Lafayette believed this in the darkest days of the fight, and because he never lied, men around him believed it too.

The war won, Lafayette went home, but in 1784, he visited George Washington at Mount Vernon, and for several glorious days they basked as father and son, home together again from long and separate journeys. The visit was bittersweet because Washington gauged it would be the last. His advancing years and the broad ocean made another unlikely. When they bade each other farewell, then, Washington said as much. “No, my dear general,” Lafayette wrote from the ship before it left to take him back to France. “Our late parting was by no means a last interview.” He knew that Washington would never come to France, but he promised “to you I shall return.”

For the first time, the young man had not quite told the truth. While George Washington lived, Lafayette would never again stroll Mount Vernon’s piazza. His visit in the mid-1820s gave him the chance to fulfill an overdue pledge. Away from the cheering throngs and apart even from his small entourage, he walked haltingly down the path from the mansion at Mount Vernon to the small crypt above the Potomac River. He stood alone for rather a long time. This, he knew, would be their last visit.

He dabbed his eyes and finally turned from the grave of the finest man he had ever known. The quiet above the river, for which he yearned, was serene, but the cheers in the distance beckoned. He would pretend the acclaim mattered, a measure of insincerity for the sake of politeness, but it was a fading echo. Jubilant crowds did not notice. Forty years could not dull their affection for the kid who had cared when it had counted the most. They too knew it would be their last visit.