When troop movements were in progress, especially when battles were joined, Abraham Lincoln almost lived at the War Department’s telegraph desk. His peaceful demeanor masked his churning worry and calmed the boys hunched over clattering keys. One day, the sounds of nearby hammering and sawing piqued his curiosity. He discovered two carpenters installing a privy in a nearby closet and afterward kept track of the project because creative manual labor fascinated him. He soon noticed a prolonged silence and found the carpenters unsure if they were to make their project a one-holer or a two-holer. Lincoln briefly glanced at the plans until he shook his head and offered some advice. “Fellers,” he twanged, “make it a one-holer. If George McClellan has a choice, he’ll puzzle over it until it’s too late.”

Perhaps the story is true, but even if it’s not, it sounds like Lincoln, whose earthy humor could range from scatological to ribald. Still, his little stories almost always aimed to state common sense or obliquely express anger. McClellan himself once sniffed that Lincoln’s “stories were seldom refined, but were always to the point,” and he would have known better than most. When it came to his general-in-chief, Lincoln wasn’t cracking wise that day with those carpenters. He was ruefully expressing a growing frustration with the young man who, just months earlier, had promised to win the war and save the Union.

Not that Lincoln was ungrateful for what McClellan had done during the nation’s darkest hour. Everyone was in despair when the thirty-five-year-old Boy Wonder came to the capital in July 1861. The nation’s principal army was shattered by its first big battle, which ended in disaster. Routed and bedraggled Union soldiers streamed back into Washington from northern Virginia to sleep in alleys and beg for food. The lucky ones camped in the Capitol’s rotunda, a grim metaphor for a government reeling under the likelihood of permanent disunion. Perhaps it had all been true, many thought; maybe the raw-boned hick somehow elected president was nothing more than a storytelling buffoon without the polish or poise of a county clerk. Some in Congress whispered as much while Lincoln’s cabinet alternated between glum silence and raucous alarm. With everything falling apart, he cloaked churning worry with a calm demeanor, but he barely concealed his desperation when he sent for George Brinton McClellan. During that awful, dismal summer, McClellan had become a bright beacon by achieving something remarkably unique for a Union general. In the mountains of western Virginia, he had won three impressive victories over Confederate forces. Such success saw McClellan bringing something even better than his sterling expertise in the military arts to Washington. George McClellan brought hope.

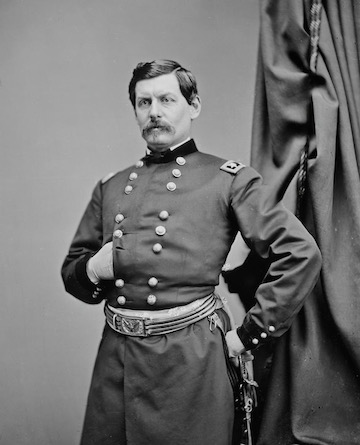

Lincoln was impressed by him from the start. Everyone was, and none more than George McClellan himself. “Who would have thought when we were married,” he wrote to his adoring wife, “that I would be so soon called to save my country?” Newspapers called him “the Young Napoleon,” and he reveled in the comparison, even posing for a photograph with his hand tucked, ala Bonaparte, in his tunic. His organizational skills and meticulous attention to detail were matched by a seemingly inexhaustible energy that even typhoid fever could blunt for only a few days. He was everywhere inspecting everything as long as there was sunlight and at his desk pouring over paperwork into the wee hours of the night. Finally aware of the breadth of the war, Lincoln unified the task of winning it by expanding McClellan’s authority to levels not seen since the days of George Washington. Lincoln almost apologized for the awful burden, but the Young Napoleon was undaunted. “I can do it all,” he said.

And in only a few weeks, he created the army to prove it. The newly formed force, dubbed the Army of the Potomac, swelled to a quarter million men. McClellan saw they were clothed comfortably, armed superbly, fed routinely, and drilled incessantly. The men developed purpose, thrived under firm but sensible discipline, and treated appreciative citizens to impressive reviews where precision, lively tunes, and pounding drums quickened pulses and swelled pride, including Abraham Lincoln’s. And yet, the president also had a slight twinge of worry, which grew larger as shadows lengthened and leaves fell from the trees and the calendar. He finally asked the Young Napoleon when he planned to win the war.

They had known each other before the war when Lincoln was a railroad lawyer. McClellan had become a railroad vice-president after resigning his commission in the US Army, a decision born of McClellan’s boredom in the peacetime army. He had seamlessly returned to civilian life because things always came easy for George McClellan. He was a child prodigy when educated in elite private schools and by demanding tutors. He was fluent in French before he was old enough for a first kiss and attended the University of Pennsylvania at the ripe old age of thirteen. His father, a renowned eye surgeon, recommended a career in law, but George gravitated to a martial calling to do great things. He was a member of the US Military Academy class commissioned in 1846, a remarkable roster of young men who would fight together in Mexico and then become celebrities, often as enemies, in the titanic war for the Union. McClellan breezed through West Point while less educated and relatively ill-prepared classmates like Tom Jackson struggled to avoid getting chucked out for academic deficiency. Both graduated, of course, with McClellan fated to become the Young Napoleon. Jackson got tagged “Stonewall.”

The nicknames revealed the two men’s different personalities with uncanny accuracy. One indicated flash and flair, while the other marked determination and will. Like everyone else, Lincoln was initially impressed by McClellan’s flash and flair, but gradually, he wanted to see some determination and will. When he got neither, he politely asked McClellan to do something with his polished-up army and then forcefully demanded it. In response, McClellan became petulant and even impertinent, speaking of Lincoln as “an odd bird” and all but rolling his eyes when the president made a point with one of his earthy stories. Lincoln wasn’t blind to this, but he was willing to ignore it if McClellan would fight the Confederacy. Perhaps before anyone else, Lincoln began to suspect he was the one dealing with the odd bird.

For it was true that the Young Napoleon was a bundle of contradictions that combined simmering insecurity with abrasive conceit. His initial victories in western Virginia revealed a fundamental emptiness in this man. He had carefully used the telegraph to publicize his exploits but had never been physically present at the fights that won him his laurels. Decisive subordinates had directed those victorious battles, but McClellan’s sense of superiority was impervious to experience, let alone evidence. However, he overthought almost everything other than his quirks and thus became prone to delusions and paranoia. He believed rebel armies vastly outnumbered him, an incredible conclusion even rank amateurs knew to be false. Meanwhile, he suspected that conspirators in the federal government were plotting his downfall.

These flaws paralyzed him, blunting his determination and shrinking his will. He contrived overly complicated campaigns to defeat enemies of supposedly boundless numbers. To thwart conspirators at his back, he consorted with political opponents of the Republican Party and, worse, sniping critics of the Lincoln administration. McClellan was never disloyal to his country, but he barely veiled his contempt for his civilian superiors, a troubling attitude for a man with 250,000 devoted soldiers. Moreover, his connection to prominent Democrats — the government’s “loyal opposition” — came naturally to McClellan, already a Democrat. Still, it was also because he agreed with them that the war should restore the Union but not end slavery. McClellan’s September 1862 “victory” at Antietam was the costliest day of the war, mainly because he mismanaged the battle, but it also allowed Lincoln to announce his emancipation policy, an idea McClellan adamantly opposed. He thought emancipation made reconciliation with the South impossible, but he also caviled at the idea of the Civil War becoming a social revolution.

Despite all this, Lincoln did not fire George McClellan in November 1862 because of his political associations or opposition to administration policy. He removed McClellan from command because he had what Lincoln called “the slows” and consequently botched the best chance anyone ever had to crush Robert E. Lee and end the rebellion. As a heroic nickname, Young Napoleon took on yet another meaning when McClellan was exiled from command the way Emperor Napoleon had been exiled to Elba.

The American Bonaparte continued to mirror the story of the Corsican, though, for just as Napoleon’s exile on Elba was relatively brief, so was McClellan’s after being relieved of command. He kept his rank, but the War Department tried to remove him from the public eye by assigning him to Trenton, New Jersey. He almost immediately moved to New York City, though, which suggested he was up to something, and Lincoln spent more time than he cared to admit worrying about it. As McClellan became the darling of newspapers and the idol of cheering crowds, whispers about a political future grew louder as the 1864 presidential election loomed.

The prospect of facing George McClellan as the Democrat nominee alarmed Abraham Lincoln, mainly because the military situation in 1864 was depressingly similar to that of previous years. New leaders with successful records seemed to make no difference. Robert E. Lee inflicted such staggering losses on the Army of the Potomac in the spring and early summer that after weeks of fighting, Ulysses S. Grant was no closer to Richmond than McClellan had been two years earlier. At the same time, William T. Sherman was stretching supply lines beyond their limits as his 100,000 men stumbled through the mountains of southeastern Tennessee into northern Georgia, fending off harassing attacks and coping with terrible terrain. A sense of general malaise colored everything, and efforts by disgruntled Republicans to replace Lincoln on the November ticket gained traction. Political conferences at the White House became gloomy rituals with long-faced counselors shaking their heads and wringing their hands. By late August, Lincoln also concluded that George McClellan would beat him.

On August 29, 1864, the Democrats held their convention in Chicago, exhilarated by the prospect of a sure victory in November. They had not, however, factored in George McClellan’s habit of putting off until tomorrow what very much needed doing within the day. At the start of the convention, McClellan was so sure of his nomination that he made no effort to control deliberations, and the forceful minority comprising the party’s “peace wing” ran wild. It drafted a platform that seriously damaged McClellan’s candidacy, some feared decisively. The platform’s most obnoxious sentiment was its most prominent feature, a pledge to negotiate peace with the Confederacy without conditions or restrictions. This declaration that the war was lost and had to be ended as soon as possible put delegates in a daze as they went through the motions of nominating George McClellan on August 31. Of course, he should have declined in protest over the platform, but that would have been a decisive move. Instead, he wrote a letter.

True enough, his letter disavowed the platform and declared that when elected, he would militarily force the Confederacy to restore the Union. However, it was hard to erase the impression that something was awry when a political party called for peace at any price while its candidate insisted on victory at all costs. Worse, McClellan and a gaggle of advisors put his letter through no less than six drafts, an editorial process that resembled one of his military campaigns as it consumed time and, finally, was overtaken by events.

McClellan did not make his letter public until September 8, seemingly oblivious to the seismic effect a telegram five days earlier had had on the country, the President, the war, and the election. “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won,” it had tersely announced to the War Department. Its author was the terse William Sherman, whose breakthrough in northern Georgia made talk of a lost war seem premature at best, perhaps even treacherous.

As he settled into bed that night, Abraham Lincoln may have remembered telling the carpenters his little story.