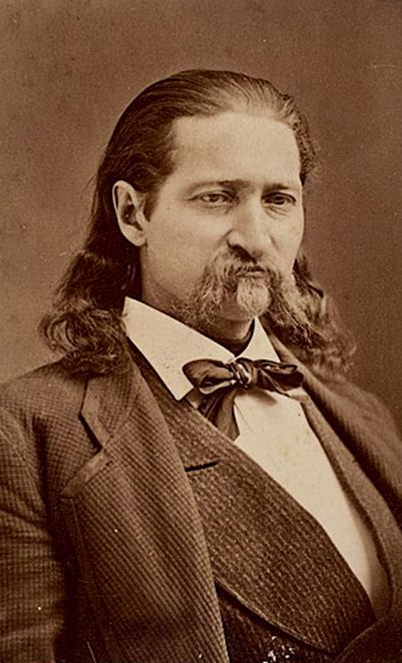

Wild Bill Hickok was an early victim of identity theft, and, like many such victims, it was partly his fault. He didn’t give his social security number and bank account information to a Nigerian promising riches, but he did give an interview to a magazine correspondent promising fame. We wonder if Hickok ever pondered the compensations of celebrity balanced against the costs of becoming a media creation, like patent medicine or bottled sarsaparilla, except in his case, purportedly armed and supposedly dangerous. The result was a mixed blessing from the start. After a time it became a curse.

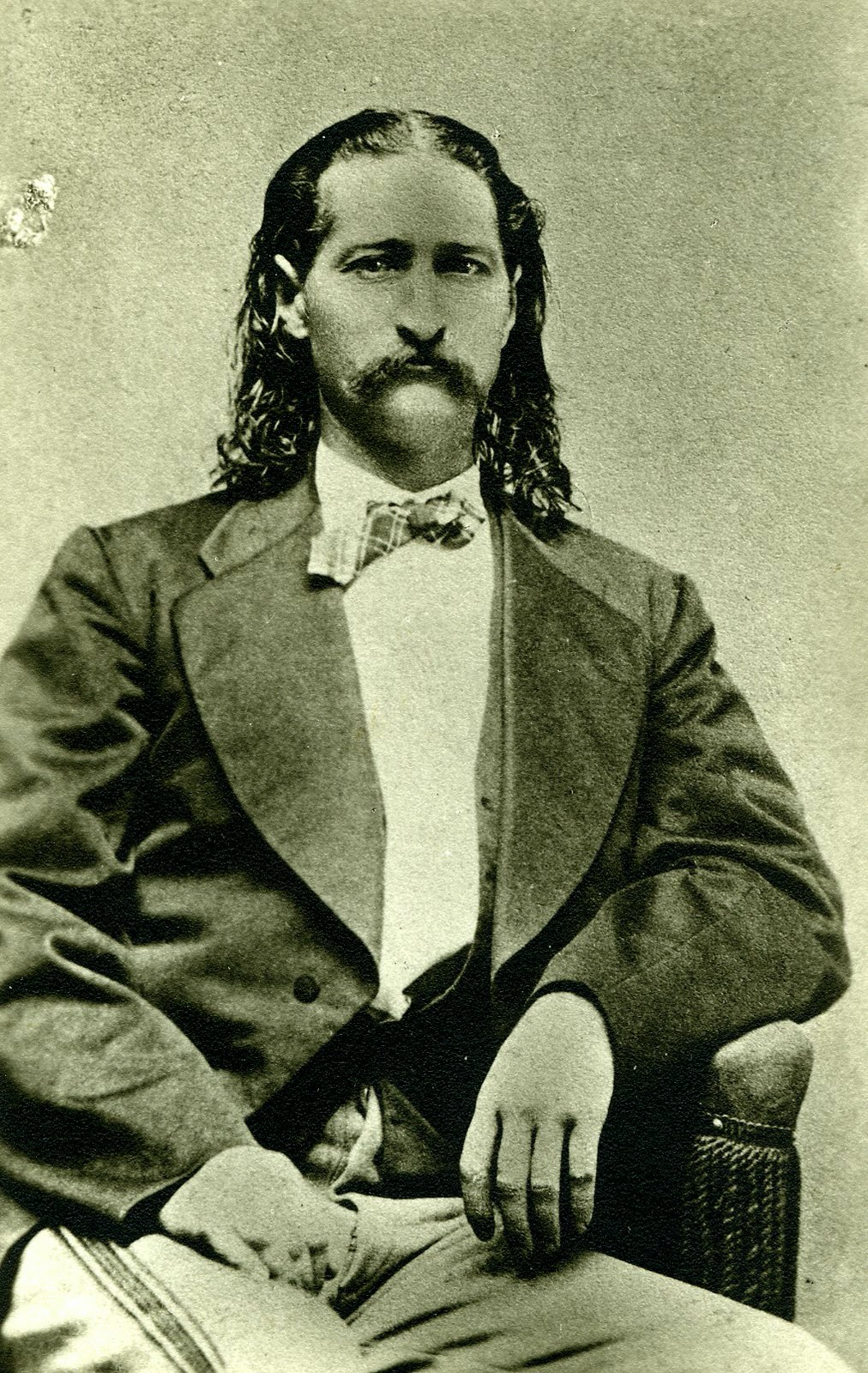

The curse caused him to lose himself. Everybody else lost him too. Every event involving this man has “various versions,” and winnowing inaccuracies to find the truth is a discouraging project. James Butler Hickok and “Wild Bill” Hickok were the same man in person, but they are not the same person in memory.

Some people swore that “Wild Bill” Hickok was a square-jawed hero of the Old West, reserved in speech, clear-eyed in manner, calm by habit, steady in mood, honest at heart. He was slow to anger but resolute when riled.

Others claimed with equal fervor that James Butler Hickok was a saddle bum who loafed at poker tables and consorted with prostitutes in seedy saloons. He was ignorant, seldom wholly sober, and had a narrow view of life that focused on practical things, such as not getting killed or drawing to an inside straight.

Likewise, Hickok’s fame as a defender of civilization in the lawless West is either aglow or gloomy.

The romantic rendition of Dime Novels and Hollywood westerns tells of beleaguered city fathers in rowdy cowtowns like Hays City and Abilene beseeching a reluctant Hickok for help. They were sick of blatant lawbreaking and swaggering punks with their pistols holstered low on thighs lounging on benches, looking for trouble, and ginning it up when none came available. Law-abiding folk were afraid of gangs that terrorized womenfolk and extorted protection money from meek merchants.

It was such places that hired “Wild Bill” as a town tamer, said the story. With a tin star nobody else dared to wear, he walked the streets unsmiling. If challenged, he was swift, unforgiving, and even lethal, but only when necessary. After killing a man who had crossed him, Hickok would pay for his funeral, a chivalric touch. In his presence, men behaved themselves, women found it hard to, and law-abiding folk rued the day he deemed his work done and left town, always heading toward the setting sun.

Others claim, however, that Hickok’s work in law enforcement was sleazy and opportunistic. City fathers soon regretted employing him after discovering “Wild Bill” was not a town tamer but a lazy louche. He ordered his deputies to patrol the streets while he idled in saloons to gamble and guzzle whiskey on the house. He sometimes colluded with the criminals he was supposed to arrest, but mostly he played at petty larceny, leveling bogus charges to shake down traveling salesmen and groggy cowboys. He could be trigger-happy and ruthless on bad days, using his office to settle scores and finish private fights. Towns who hired him eventually fired him and were never sorry to see him leave.

Confronting such contradictions has caused many to shrug off both sides with the recommendation to “take your pick” — Hickok as conquering hero or craven coward, six of one, and all that. But adopting that attitude does more than offend a pedant. It does the man, his family, his friends, his acquaintances, even his enemies, and the past they all inhabited a significant injustice.

The Dime Novel was a pack of lies, and Hollywood westerns are often fanciful frauds. But urbane critics sniffing over laudatory treatments are no better. When they set out to expose storybook illusions about the past, they can inflict equal injury with seemingly plausible but flimsy claims. Gary Cooper’s Hickok in The Plainsman is too good to be true, but Keith Carradine’s Wild Bill in Deadwood is too real to be discounted. Both, however, are fictional creations using the actual name of a real man as an alias. In real life, that’s called identity theft, which, as they used to say in movie theaters, is where we came in.

So far, then, the only sure thing about Hickok’s story is that he lived. That slender thread of truth, though, presents us with more than a fact. It imposes an obligation to avoid unfair slander and withhold underserved applause with equal caution. The careful student of the past is prudent about naming saints and sinners because names are possessions, and their owners have a claim to them by way of headstones if nothing else. Disclaiming “any resemblance to persons living or dead” on the flyleaf of a novel or in the closing credits of a movie is vice’s tribute to virtue. But the claim, even if tacit, of “based on a true story” requires us to leave our firearms of partisanship, political agendas, and special pleading with the bartender. Only then are we allowed to fill glasses and swap lies.

Here is what we know.

In 1856, a tall, skinny eighteen-year-old kid with blue eyes and a humble manner left his family in Illinois and headed for the Kansas frontier. His name was James Butler Hickok, “Jim” to family and friends. Twenty years later, on August 2 in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, a feckless prospector named Jack McCall shot Hickok, by then known as “Wild Bill,” in the back of the head killing him instantly. Between those two events occurred a series of purported adventures that in print and on film have captivated generations of Americans. Most of them either never happened or happened in ways significantly different than portrayed.

In 1856, Jim planned to claim a homestead and start a farm, but he didn’t like the work. In short, Hickok, as either boy or man, didn’t like work, period. Employed by a stagecoach and freight line, he became a hostler at a station in Rock Creek, Nebraska, where, on July 12, 1861, he shot David McCanles dead with a rifle.

To his credit, this first killing shamed young Hickok, for it was an ugly deed with an obscure motive. McCanles was unarmed, and Jim shot him while hiding behind a curtain. A jury ruled it self-defense, which often happened in raw places during those rough times. The place, the times, and the advent of the Civil War in the West seem to have rubbed down the jagged edges of the lad’s recollection of killing Dave McCanles.

Exposed to terrible violence and incredible risks during the war, Hickok proved himself courageous and resourceful — a fact confirmed by the army occasionally employing him as a scout during Indian campaigns — but the war changed him. Life was cheaper, his included, and he blithely risked it in the gunfight with Davis Tutt over a gold Waltham timepiece. Just days later, he bragged about killing Tutt and, incredibly, invented a fantastic tale about killing Dave McCanles at Rock Creek four years earlier. His listener was George Ward Nichols, a writer for Harper’s Monthly Magazine.

Why Hickok lied to Nichols is a mystery. He might have thought it a ripping good prank to pull on a scribbler, but he was, in reality, doing more than forfeiting his identity. He was selling his soul, and on the cheap at that.

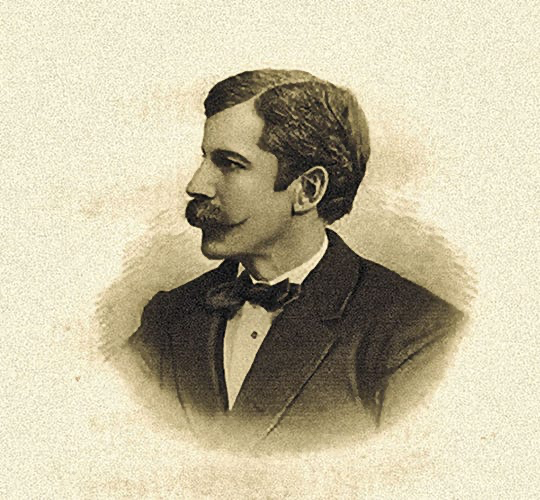

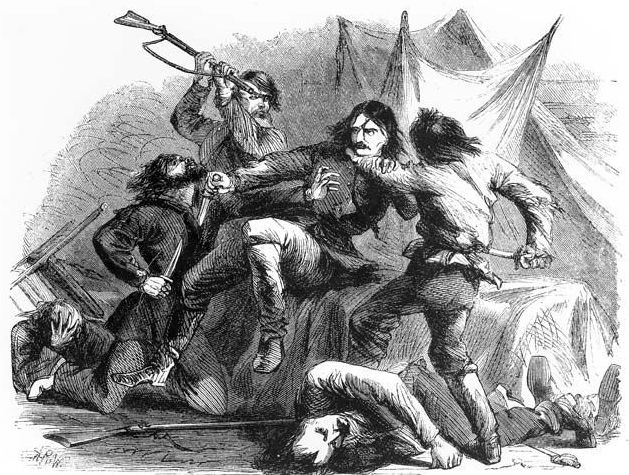

Harper’s Monthly had almost a quarter-million readers, and its lead article in February 1867 told them the story of “Wild Bill,” peerless Union army scout, and supernaturally gifted marksman. With eye-catching illustrations in twelve long pages, everything about J. B. Hickok was either grossly distorted or wholly untrue. The article’s centerpiece was the killing at Rock Creek in which “Wild Bill” fought a bloodthirsty gang of pro-Confederate ruffians, ten in number, dispatching them all with his pistol, his knife, and his bare hands.

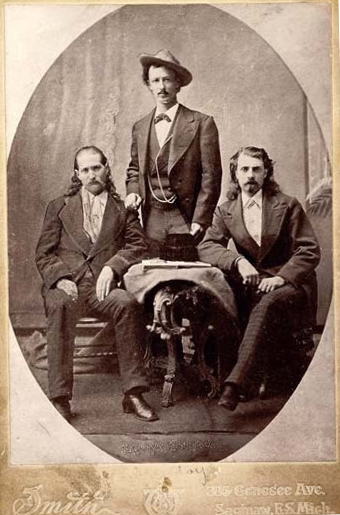

Harper’s made him instantly famous and widely admired as the gunmen who challenged badmen with moral integrity and a Navy Colt revolver. The new image seemed like a golden gift. It transformed a vagabond who had killed one man from concealment and another over a watch into a hero. Aided by Nichols’ imaginative writing, Hickok even enlarged on the tale by claiming to another correspondent that he had “killed considerable over a hundred” men. Colorful copy about him became stock column fillers for newspapers from Savannah, Georgia, to Sacramento, California. For the next few years, being famous paid many rewards. Women were among them, nervous respect from otherwise ornery men was another, and there was even a stint in show business when “Buffalo Bill” Cody tapped Hickok to play-act western dramas in his Wild West show.

All of these became wormwood on the drifter’s tongue. The women were always whores; the ornery men gradually made him paranoid about doors and chairs that didn’t back to a wall. Buffalo Bill’s gig was repetitive, grinding work that tired him out while boring him to tears.

In fact, the adventurous life of Wild Bill Hickok was a tedious series of sameness infrequently interrupted by sharp, brief instances of danger. Rather than “hundreds,” Hickok killed a total of eight men in his entire life. After Dave McCanles in 1861, his dispatch of Davis Tutt, in 1867, was the only showdown in a public street. All the others happened in the next four years and, except for one, resulted from Hickok’s service in law enforcement.

In Hays City, he killed a drunken Bill Mulvey to stop him from shooting up the place. He shot dead Sam Strawhum for snidely challenging his authority. He was drinking in a Hays City saloon when a couple of army troopers from the Seventh Cavalry tried to murder him (reason unknown) before he maimed one and mortally wounded the other, John Kyle. During his eight months as Abilene’s marshal in 1871, he killed only two men, Phil Coe, a saloon owner who discharged a firearm in the city limits and refused to surrender it. When he foolishly pointed it at Hickok, Wild Bill killed him.

Then, as Hickok shot Coe, he glimpsed a man running around a street corner toward them. Wild Bill reflexively shot him dead too but immediately realized the victim was Mike Williams, his deputy, who had been rushing to his defense. The mistake seems to have shattered Wild Bill. No documentary evidence or anecdotal account describes him even pointing his gun at another person during his remaining five years.

Abilene’s citizens and council liked him but didn’t renew his contract, apparently because he was expensive and they didn’t need a “town tamer” any longer. He never again put on a tin badge. Instead, he gambled and drifted, sometimes flush from winnings, increasingly verging on vagrancy, and always watching his back. According to some, he noticed a frightening development that possibly contributed to his killing of Mike Williams. His eyes were giving him trouble. In early 1876, a Kansas City doctor told him that he was going blind. At least, that’s one version of the story.

And perhaps it’s true, because in 1876, he finally married. His bride was at least ten years his senior, a widow named Agnes Lake, and their union was likely a business arrangement. Agnes owned a prosperous circus, and Hickok’s name still had a bit of luster, so both were looking to the future. Even so, after they said their vows on March 5, Hickok left Agnes in Cincinnati and tagged along with a wagon train that arrived in July 1876 in Deadwood. The place was a newly minted town full of gold dust and bored prospectors willing to risk it at cards. Another drifter tagging along with the wagon train was a hard-bitten gal named Martha Jane Cannary, who was introduced to Wild Bill as Calamity Jane. Despite the tales of romance and the claims of their intimacy by a “descendant,” they hardly knew each other. There are, yes, various versions.

Wild Bill Hickok was playing poker in Deadwood on August 2, 1876 when he drew a relatively good hand of two pair, the Ace of clubs and spades, and eights of the same suits, and he was assessing these cards when Jack McCall shot him in the back of his head. For the first time anyone could remember, Hickok was sitting with his back to the room. Possibly it was for the better light, but McCall, bitter over losing a considerable sum to Hickok the day before, saw his opportunity. The bullet exited Hickok’s cheek and lodged in the wrist of another player. McCall’s lie that he was avenging a brother killed by Hickok won him an acquittal from an irregular proceeding in Deadwood, but his later boasting about the lie got McCall a new trial, a guilty verdict, and a noose.

Within hours of Wild Bill’s murder, all of Deadwood had turned out to bury him in a plain pine box. Summer heat dictated haste, so there was some surprise three years later when plans to move the cemetery required exhuming its dead, and everyone expected Wild Bill to be a box of skeletal remains. Sure enough, Hickok’s coffin had considerably deteriorated in the damp soil, but struggling workmen found it monstrously heavy. When they opened it, they discovered that a mixture of moisture and minerals had been petrifying Hickok’s remains. Roughly half of him had become stone.

Over the years, Deadwood cashed in on the new site of Hickok’s grave as a tourist attraction with gimmicks such as burying Calamity Jane nearby and erecting a series of headstone statues that souvenir hunters regularly whittled away with chisels. Eventually, a barrier around the grave discouraged pilgrim vandals, but it also played a sad joke on the drifter below. Someone had finally fenced him in.

Hickok likely doesn’t care. He seems to have gotten accustomed to something he wasn’t getting mixed up with someone he was. Now, below the earth, two men lie in one casket as a whole made into halves. One half is petrified Wild Bill, the unreal stone monument of Dime Novels and western films. The other half is the real person, the one who virtually vanished during life, but in death, went to dust as he was supposed to. Before the killing started, he was just Jim. After the dying, it was Jim who headed home.

Excellent read! Couldn’t wait for this post to read the rest of the story.