By the summer of 1794, disagreements over America’s domestic and foreign policy had seen organized dissent in the form of Democratic Societies increasing throughout the nation. Alexander Hamilton and many Federalists judged the development as subversive, even perhaps an emulation of the French Revolution to overthrow the government. The societies saw themselves as keepers of America’s revolutionary flame, lights of liberty that embraced simple republican principles in the spirit of 1776.

The base of the dispute was that Federalists didn’t embrace citizen participation in politics beyond casting votes in legitimate elections. Republicans believed that Americans should keep their elected representatives aware of their views, especially if they thought government policies were disagreeable. Federalists had come to regard even mildly boisterous dissent as seditious. The Democratic Societies said things at their meetings, in the press, and even in letters addressed to President George Washington that Federalists judged rude and impertinent. Washington was inclined to agree. It was not a new attitude but one old and venerable, a tradition of colonial politics in Virginia grounded in deference to propertied planters whose legislative seats were virtually hereditary and whose decisions were beyond question. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton believed this because of his temperament rather than his experience. He regarded the people as a great beast that had to be kept passive lest it became violent.

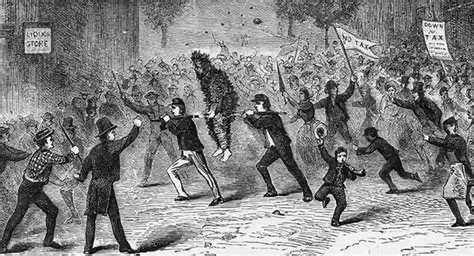

This attitude was the governing party’s frame of mind when it received reports about a large group of armed protestors in western Pennsylvania burning down the house of a tax collector. The attack was only the most recent in violent outbreaks over a federal whiskey tax. Disturbances related to Alexander Hamilton’s excise had periodically occurred in the western parts of many states, but they were usually written off as instances of frontier exuberance, the way pioneer folk expressed themselves when ornery. Some of these incidents were serious, though, as in 1792 when they turned mean and rough in western Pennsylvania.

At the time, Hamilton had urged using force, but Washington preferred words. He issued a proclamation in the hope that the protestors would settle down, and they had. They almost always did. But the discontent did not go away, and expressions of it in 1794 featured more than tar, feathers, and a few potshots at some “revenuers.” Federalists saw this behavior as the inevitable result of Republican efforts to undermine the government. Arson by a mob targeting a government agent caused Washington’s entire cabinet to agree that a military response at least should be readied.

The administration thus began putting its constabulary ducks in a row. Alexander Hamilton insisted that if the rebels continued to defy the law with impunity, the survival of the national government was at risk and that only force would hammer some deference into the great beast. Yet Attorney-General Edmund Randolph observed that only the people’s affection could make the government secure. He made a persuasive argument for sending a peace commission to meet with the rebels. Washington listened to Randolph and decided to appoint three Pennsylvanians to open talks. The state’s Attorney General William Bradford, Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Jasper Yeates, and Federalist Senator James Ross could not be seen as meddlesome outsiders. Ross even lived in western Pennsylvania, which made him a neighbor, so to speak, and already on site because Congress was not in session. Washington gave the commissioners the power to grant amnesty and waive back taxes.

It was difficult by that time to judge how bad the situation in western Pennsylvania had become. A meeting of several thousand insurgents near Pittsburgh suggested widespread discontent and a troubling level of organization. Yeates and Bradford left to join Ross in the rebellious counties, and Washington issued another proclamation telling the insurgents to disperse and go home. He warned them he would call up neighboring state militias to stop the unrest if it continued.

The commissioners were soon discouraged by their visit. Bradford and Yeates met the burned-out tax collector as they traveled and found him understandably bitter about losing his house to a mob. He doubted the rebels would lay down their weapons, and when James Ross joined them, he was also gloomy. He knew that cooler heads were ready to accept terms, including swearing an oath at their local polling places, but hardliners were threatening those who wanted to back down. Bradford wrote to Washington that he believed the rebels were stalling, hoping that winter weather would prevent a military expedition that year.

By August 23, Washington had decided that force was necessary, especially when new rumors told of insurgents planning to break the western Pennsylvania counties away from the state (and consequently the United States) to seek a union with Great Britain. The summoning of 12,000 militia troops from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia was a sobering development. Perhaps this dire step had to be taken, but it was unfortunate that it was taken the way it was. Because Secretary of War Henry Knox was away on personal business, Alexander Hamilton stepped in as the acting Secretary of War. His involvement made the affair look like a political effort to stifle dissent rather than a reasonable plan to restore order.

The call for troops was unprecedented, and Washington worried that the militia might refuse to show up. He and acting Secretary Hamilton traveled to a militia rendezvous near Carlisle and were heartened to see growing numbers mustering. Governor Henry Lee of Virginia also arrived, and Washington was relieved that he could have his friend “Light-Horse Harry” conduct the campaign while he returned to Philadelphia. In any case, Washington should have planned to take Hamilton with him, for Hamilton’s plan to tag along with the militia march compounded the political blunder of his role so far. It raised suspicions that he had inflated the crisis to make odious military force appear necessary.

Before Washington left Carlisle, David Reddick and Pennsylvania Congressmen William Findley brought a message from the “Whiskey Boys” that, given time, they would meet the government’s demands. Washington was initially encouraged enough to meet with Reddick and Findley several times, but he could never get them to prove that the rebellion was over. The season was growing late, and Washington recalled the warnings from his commissioners that stalling was a rebel strategy. He decided to allow the large militia force to proceed westward and canceled plans to leave it. Instead, he too moved forward to the endmost rendezvous point at Fort Cumberland and then to Bedford for a final review of the troops. By this time, they were an impressive force of some 13,000.

Findley and Reddick begged Washington to lead the expedition, having sensed that Alexander Hamilton, tricked out in a tailored army uniform, was enjoying himself too much. But Washington insisted on returning to Philadelphia while Harry Lee, with Hamilton at his side, led the troops toward the scenes of rebellion. They encountered no disorder, let alone violent unrest. As soldiers approached, insurgents scattered. The Whiskey Rebellion was over. It is usually interpreted as a potentially dangerous time whose happy conclusion established the federal government’s ability to enforce laws without relying on the states.

However, the impression at the time was not nearly so salutary among growing swaths of the American public. It had been a small affair — fewer than five Whiskey Boys were killed — but its very smallness meant that the repercussions over the manner of suppressing it were significant. The federal government’s authority to enforce the law was one thing, but swatting a fly with a bludgeon was quite another. More than a few Americans wondered why it had been done.

Thoughtful men frowned over the extraordinary display of force and Hamilton’s eagerness to use it. Equally troubling was the behavior of authorities after the “insurrection.” Militia commanders had names and knew the houses they belonged to. All dressed up but with no one to shoot, troops began dragging people out of those houses and subjecting them to menacing interrogations. These were conducted by Alexander Hamilton, who was enjoying himself very much indeed. He had about twenty men arrested and paraded back to Philadelphia. Some were forced to wear hand-lettered signs labeling them as “traitors.”

George Washington had assured everyone that this sort of thing would not happen. Yet, Alexander Hamilton’s interrogations were appalling. The crude branding of prisoners as “traitors” without trial was shocking. And when two detainees were eventually convicted and sentenced to death, the nature of the proceedings and the unduly harsh judgments courted the creation of martyrs.

President Washington still seethed over the Democratic Societies, and moods on both sides of the question remained somber and suspicious. The Revolutionary War — the grueling fight to secure the country’s independence and ensure its liberty — had been won only a little more than ten years earlier, and the country now had government agents knocking down doors and arresting “ringleaders.” The eerie resemblance to the events at Lexington and Concord came to mind for some. The pandemonium recently promoted by militants in the streets of Paris occurred to others.

Suspicions thus persisted about excesses of government power and limits on citizen dissent. Questions plagued the polity. When did government enforcement become government tyranny? When did liberty become license? Definitive answers to those questions eluded those Americans, but one certainty in the mind of the nation’s premier Founder was clear and unwavering. Nobody would find the answers in jail cells or on gallows. President George Washington immediately pardoned and set free the two men who had been sentenced to death. Everyone, everyone, would have time to think.