Just when George Washington thought things could get no worse, a crisp October day opened with an unexpected visitor to his headquarters. She was a woman of middle-age, an aristocrat by appearance and manner but with a somber nature, possibly because of her errand, perhaps because of something else. She carried a sealed packet of papers, which she explained was a letter meant for the commander-in-chief. Her name — Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson — as well as her demeanor alerted everyone that she was from the highest rung of Philadelphia society, and she was admitted to see the general immediately.

George Washington did not know her, but he certainly knew about her. Dr. Thomas Graeme, Philadelphia’s Port Physician for many years before his death in 1772, had been her father, and the family home at Graeme Park was admired for both architectural splendor and understated elegance. Washington could not have been but curious about her errand and the letter she carried. She revealed its author when handing it to him as the Reverend Jacob Duché, a man whom Washington and many other American patriots greatly admired. And yet, only moments after Washington broke the seal on the packet and began reading Duché’s words, he deeply regretted ever laying eyes on Mrs. Fergusson and opening the letter she had given him.

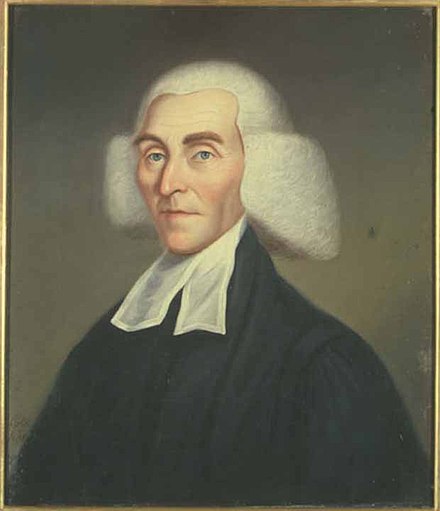

The three principals in this strange story were singularly unhappy people at this pivotal moment. Mrs. Fergusson, the letter bearer, was “Betsy” to friends and family, but the diminutive disguised a serious nature made melancholy by a failing marriage. The Rev. Duché, the letter writer, was the rector of Philadelphia’s Christ Church, but he was also a pathetic hypochondriac easily swayed by acclaim and given to bouts of crippling self-doubt. He had been swept along by revolutionary fervor in 1774 and was celebrated for his eloquent prayers invoking God in the American cause and exhorting soldiers to fight for American liberty. Yet, Duché’s growing doubts about American independence and his revulsion over bloodshed to achieve it eventually made him pause over the entire project. In early October 1777, he ceased pausing and acted to write an incredible message to George Washington, laying bare his soul and urging the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army to take extraordinary action.

For George Washington, it had been an awful year capped by a dreadful autumn. He had concluded 1776 with a stirring victory at Trenton, New Jersey, on Christmas Day. But that achievement, later memorialized in the famous painting of him resolutely crossing the Delaware River, had only briefly silenced critics convinced of his sketchy martial competence. Their carping resumed in 1777 as spring and summer passed with no victories, and then September brought a stunning defeat. General William Howe pushed aside the Continental Army to take the putative American capital of Philadelphia. The British occupation sent Congress scurrying across the Susquehanna River, where it huddled like a gaggle of hapless refugees in York. More than a few in Congress no longer hid their contempt for George Washington and his ineffectual army, and another defeat on October 4 at Germantown persuaded many that it was time to remove him from command. A few delegates already had a replacement in mind.

It was during those dark hours that Jacob Duché on October 8 drafted a long letter of fourteen pages and entrusted it to Betsy Fergusson’s Loyalist husband, who urged her to take it to Washington a week later. The cordial pleasantries she exchanged with the general, however, gave way to an ominous silence as his jaw tightened and his brow knitted while he read the letter. He finally raised his eyes and leveled an icy gaze on his visitor before saying in calm but clipped tones that he was sorely disappointed in her for undertaking this foolish and unseemly errand. Had he known what was in the letter, he said, he never would have accepted it, let alone opened it. Much to his everlasting regret, it could not now be unread, but he made clear that he expected her never to engage in such a disgraceful gesture again. Mrs. Fergusson, who counted the acclaimed novelist Laurence Sterne a friend and once casually conversed with King George III, had never been flustered in her life, but the stare from Washington’s cold blue eyes unnerved her. She hurried away from headquarters.

His uncharacteristically stern reaction aside, General Washington had been quite candid with his visitor. He would have given anything never to have read Jacob Duché’s strange letter. It opened with a bizarre concoction of apologies and explanations, the one for disloyalty to the King, the other for his deceit toward Americans. Duché then got down to cases. He condemned Congress as a collection of pettifoggers and assessed the Continental Army as fickle and faithless. Neither was capable of defeating the invincible British, said Duché, so it was urgent for Washington to persuade Congress to repeal the Declaration of Independence and open negotiations to stop the war and bring about a reconciliation with Crown and Parliament. If Congress resisted these recommendations, Duché insisted that Washington should engage in private talks with the British. The implication was that he should use his military authority to bypass elected representatives and make policy as he saw fit.

A wave of conflicting emotions washed over George Washington as he pondered the meaning of Jacob Duché’s letter and what he knew he must do about it. He was both horrified and puzzled. The minister had remained in Philadelphia when the British marched in and had been briefly jailed for his earlier support of the Patriot cause. Had he purchased his release by betraying that cause, or was he being truthful that he now spoke his conscience without the slightest coercion? Either way, Washington had to wonder how many men like this wandered the American landscape, talking loudly of liberty and loyalty before lurking in shadows to whisper treason. The prospect unnerved as well as dispirited him, which was why he had dropped all but the iciest courtesy toward Mrs. Fergusson. That woman carrying that man’s awful letter, bringing it through the encampment of gaunt men dressed in tatters and bleeding through the soles of shoeless feet, infuriated him.

Washington knew that if he pretended that this had never happened, it would be worse in the end, for the incident would be discovered sooner or later, and possibly at the worst time. Keeping the matter secret would make it appear that he had contemplated joining a conspiracy against the people he was sworn to serve. Even more, the letter assailed Washington’s fundamental and unshakeable belief that civilian control of the military was crucial in times of both war and peace. Roman history was a long chronicle of popular generals using their armies to become dictators, with Julius Caesar only the most famous to rearrange government and don the frock of tyranny. The British experience was also a cautionary tale of how things can go horribly wrong when generals forget their place and act from political motives. Oliver Cromwell was an example of the trap in dissolving legislatures and imposing order with force. George Washington might not have been able to win a battle to silence his critics, but he was not going to silence critics by turning their army on them. He was not going to kill American liberty in its cradle.

General Washington promptly sent the letter to Congress. His cover note remarked on its substance in muted terms that framed it as more curious than perilous. But he made plain with the gesture that he was reporting as a subordinate to civilian superiors about a matter involving everyone’s relationship to one another. He was somewhat dismayed — though likely not surprised — that someone in Congress made Duché’s letter public, with the result that the minister was transformed overnight from a hero to a figure so reviled that he feared for his safety. And Washington likely looked down with a tightened jaw when much of Congress overlooked his subordination of self and station to its institutional supremacy. Congress did not appreciate what they had in this man.

The gaunt men in tatters recognized the worth of this man, though. When George Washington looked down with welling eyes at bloodstained footprints in the snow, he never doubted what he and these men were doing. There would come a time when some of them would forget this and ask him to do essentially what Duché had suggested, to take matters into his own hands because he knew better than the politicians.

But when that time came, George Washington would again say no. He would never forget his place and his duty within it. The frock of tyranny, no matter how stylish at the moment, ill-fitted him. Mrs. Fergusson, remembering his expression and tone of voice, could have told everyone a great deal about that.