And he who sat on it

had the name Death

In our time, there is some comfort in that science can identify the cause of illness and seek effective treatments while alleviating distress. Our forebears did not have even that small comfort and thus not only struggled with deadly afflictions but stumbled through the darkness of uncertainty while doing so. In 1793, the new constitutional government of the United States had not yet existed for five years, but its capital city suffered a catastrophe that still beggars the imagination. Our story begins, as you’ll see, with a young woman living in the residence of the President of the United States. Her maiden name was Mary Long, but to friends, she was always “Polly,” and her closest friend was her childhood sweetheart and husband, who happened to be George Washington’s private secretary.

When the rampaging pestilence abated in 1793, survivors gave thanks to God. They then rolled up their sleeves. The time will come when we will do the same with the Wuhan Virus. We join everyone in praying that the time is soon.

That summer, Polly Lear became seriously ill and rapidly declined. In only days, Tobias Lear’s young wife and mother of his child died on Sunday afternoon, July 28. The heat compelled them to bury her in haste, so the next day her funeral was held that afternoon with Supreme Court Associate Justices Wilson, Peters, and Iredell walking solemnly with Cabinet members Alexander Hamilton, Henry Knox, and Thomas Jefferson as Polly’s pallbearers. President George Washington stood with Lear during the ceremony.

Polly’s death nearly killed Toby and cast a pall over the Washington household. He had loved her “from infancy” and now was alone with a two-year-old son. The family had been excited about embarking on a new life with Lear setting up a business and settling them in a place of their own. Then the illness came, and she was suddenly gone, blasting a hole in his life and bewildering the little boy. George and Martha knew loss, but Polly’s death seemed remarkably tragic. Vibrant and kind, the young woman had been Martha’s companion and kin, but for the bloodline.

Polly’s death was more than a tragedy, however. It was an omen of horrible things coming to Philadelphia. Modern students know what killed Polly Lear, but at the time, physicians were at first baffled. They, too, would soon know what killed her, but they never would know what caused it. She was one of the earliest victims of the yellow fever outbreak that terrorized Philadelphia, beginning in the summer of 1793 and lasting more than three months. Relatively few deaths marked the weeks of its early appearance, and doctors were slow to realize what they faced. By the first week of September, they knew all too well what they faced.

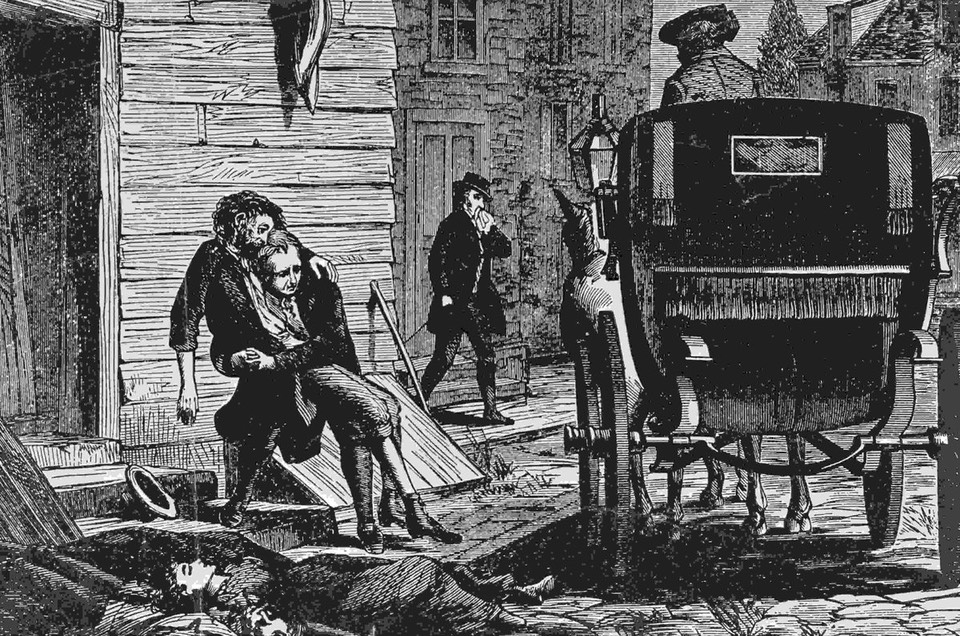

City leaders did their best to organize medical care and efficient burials, the one dreadfully ineffective and the other worse than somber as the numbers of dead multiplied. Many fled though with few options for destinations as other cities barred people coming from Philadelphia because of fears over contagion. Yet no one knew what caused yellow fever. In Philadelphia, experts blamed lousy air coming from the harbor’s fetid water as much as contagion. Mosquitos seemed unusually thick during the late summer of 1793, but no one made the connection. No one would make the connection for more than a century.

Even the most sheltered citizens were soon well aware, however, that yellow fever was a horrifying malady that tortured victims before killing them. A low fever, listlessness, and aches signaled its onset. A rising temperature soon came on, sometimes to break briefly and kindle hopes of recovery. After a short time, though, the fever returned, raging. A jaundiced complexion gave the disease its name, liver failure being an early development with internal bleeding, vomiting, and diarrhea. The last stage of the illness turned bedridden victims into invalids. Those who lived alone or were abandoned by frightened relatives died in their own filth.

By mid-September, Philadelphia resembled a ghost town. Stores closed, newspapers stopped printing, and government work ceased. Some of Washington’s official family were among the refugees, but Alexander Hamilton and his wife Betsy began showing signs of the disease. By September 8, they were confirmed cases.

Hamilton was treated by Dr. Edward Stevens, who hailed from St. Croix and had been a boyhood friend in the West Indies. Stevens was a product of the University of Edinburgh and subscribed to treating yellow fever with cold baths, a therapy that came to be known as the West Indies treatment. The Edwards method was in direct contradiction to the famed physician Benjamin Rush’s advocacy of bleeding and blistering, the depletion treatment. Bleeding and blistering were Rush’s preferred treatments for everything, and they could often kill instead of cure. Hamilton’s recovery did much to boost the popularity of the West Indies treatment, and he recommended Stevens and his methods to the college of physicians. But yellow fever, like everything else, showed the preoccupation of the times. The rival West Indies and depletion methods became embroiled in politics with Stevens’s ideas cited as the Federalist cure and Rush’s as the Republican one.

Hamilton and Besty’s recovery did not end their troubles. When Hamilton finally took his family out of town to what he hoped would be the safety of her father’s New York home, the journey and destination became complicated. People along the way feared the Hamiltons were bringing the fever with them, possibly through something on their clothes or themselves or their servants. Albany’s city government passed resolutions quarantining them and barring Philip Schuyler from town. Hamilton reared up. The clothes were clean, he insisted, servants could be left behind, and he and Eliza were not contagious. Albany’s mayor remained unmoved. All he needed to know was that Hamilton had recently come from Philadelphia, something that required the city to guard its citizens against the disease. Politics colored everything. Albany’s authorities were Antifederalists.

Jefferson left Philadelphia with his younger daughter, Maria, who had been living with her father for about a year. He had planned the trip to Monticello for the fall, but his concerns for the child caused him to start early. Knox and Attorney General Edmund Randolph left as well, though Randolph only went as far as Germantown where the disease had not reached. That town was nearly bursting at the seams with refugees. People everywhere urged Washington to leave Philadelphia for his “own sake & that of mankind,” but he recoiled from the potential charge that, like a cowardly captain, he had jumped a sinking ship. It was Martha’s refusal to leave without him that caused him to move up his fall journey home.

The Washingtons invited their friends Samuel and Eliza Powel to come with them, but former Philadelphia mayor Samuel refused to leave, and Eliza would not go without him. They were one of those seemingly mismatched couples that nobody can understand. She was all sparkles. He was quiet and bookish. True enough, Samuel Powel was wealthy, but that had meant little to Elizabeth Willing, whose family ranked with the Powels and Binghams as among Philadelphia’s wealthiest clans. No, there had been something perfectly complementary about Samuel Powel and Eliza Willing that they had quickly realized if nobody else could. She could have married anyone in Philadelphia, but she chose him, and he her. If she would not cast him aside as a suitor because some ninnies thought him too plain and her too pretty, she was not going to leave because of a silly epidemic. George and Martha Washington left Philadelphia while the Powels remained.

As the scope of the diseased worsened, Powel persuaded Eliza at least to go to her brother’s home in the country. In due course, he also retreated to his country house. The need for “a humane visit” to look after a servant brought him back into Philadelphia, however, which his friends knew was just the kind of thing he would do. Samuel contracted yellow fever. Dr. Rush bled him until he died. Years earlier, young Eliza Powel had born the indescribable grief of losing two small children, but losing Samuel was different. She would never again laugh as heartily, never again wish to preside over a sparkling party without the gentle soul who had courted the improbable girl and lived the exquisitely caring life. Eliza survived the great yellow fever epidemic of 1793. Her heart would have begged to differ.

Amid wrenching personal loss, official life went on. As soon as Washington arrived at Mount Vernon, he began worrying about the upcoming meeting of Congress. He asked how to arrange for Congress to meet someplace other than Philadelphia. The crucial part of Washington’s question, however, concerned who had the authority to designate an alternative site. Jefferson visited Mount Vernon on his way home and told Washington that the President did not have the power to select another location. Attorney General Randolph agreed.

The specter of Congress missing its scheduled opening unnerved Washington because he thought it would set an exceedingly bad precedent. He yearned to have someone credible tell him that he could name a place other than the plague-ridden capital where Congress could temporarily conduct business. Washington even asked Madison’s opinion but was disappointed by him as well. Madison, like Randolph and Jefferson, said that only Congress could change its meeting place.

Washington planned to return to Pennsylvania, if not Philadelphia, in the third week in October. He told Randolph to find him a house in Germantown and summoned others in the cabinet to meet him there. An urgent sense drove him to conclude he had to get at least his part of the government in operation. Jefferson met Washington early along the way and made most of the journey with the President. In Germantown, Jefferson was surprised by the mass of people. He managed to rent a bed in the public room of an inn, and though he had to share the space with snoring sleepers, Jefferson was grateful to have it.

The fever was abating but still lingered in Philadelphia, lethal but waning. About four to five thousand people had died, which was a devastating shock to the city’s population, amounting to a mortality rate of about 17%. (A comparable figure for today’s population would be about 275,000 deaths.)

Still, many recent cases seemed to be less severe, and as the city took stock, it counted scores of people who had performed heroic acts of kindness and courage. Wealthy philanthropist Stephen Girard had established a hospital at Bush Hill, the mansion formerly occupied by Vice President Adams. Mayor Matthew Clarkson became an indispensable coordinator of ad hoc but effective tactics to ease suffering and provide essential services. Physicians refused to bleed patients to death, and not because those doctors were Federalists but from their commonsense preference for gentler treatments. Two black ministers named Absalom Jones and Richard Allen selflessly nursed as well as comforted Philadelphia’s poorest citizens.

Into November, Washington met with his cabinet in Germantown, but he continued nervously counting the hours until Congress was supposed to convene in December. After hearing that no new cases of the fever had occurred for several days, Washington slipped away alone to visit Philadelphia on horseback. When he returned, everyone was shocked by his recklessness, but what he had seen convinced Washington the fever was gone. He calmly told them it was past time to get back to work.

Hard frosts had ended the nightmare. No one knew why. Over the next few days, congressmen, senators, and other government officials began trickling back into town. Much unfinished business remained from the terrifying summer. The President’s advice took hold of the government. It was time to get back to work.