The locomotive chuffed into Tuscumbia, Alabama. On the depot platform, the anxious family waited. A little girl appeared at the door of the coach. She wore a trim dress, and her hair was in soft curls. Just behind her stood a self-assured young woman, a confident tilt to her head and her hand on the girl’s shoulder. As the two descended to the platform, the family did not speak, but the mother moved briskly to hug the little girl. Feeling her mother’s hand, the child said, “Mama,” and it was then that Mama burst into tears. She folded her daughter into her arms.

The young woman hung back, not so confident as she seemed after all. She watched the father and was disappointed to see him turn away. Then she saw him pull a handkerchief from his coat and hold it to his face, a gesture he tried to hide. The young woman understood. Mildred, the little girl’s little sister, broke into a jubilant dance. The mother was hugging the little girl so tightly she muffled what had become a torrent of rapid words and gushing phrases.

To her family, it was beyond belief that Helen was talking. Annie Sullivan smiled over something that was completely and without qualification Good. It made both teacher and pupil think of Isaiah.

The scene on the platform took place at a point beyond the dramatic climax of a famous Broadway play and the movie based on it. Playwright William Gibson told the true story of Annie Sullivan and Helen Keller in The Miracle Worker, an apt title for the story of how a dedicated teacher with the patience of Job changed the life of a blind and deaf child.

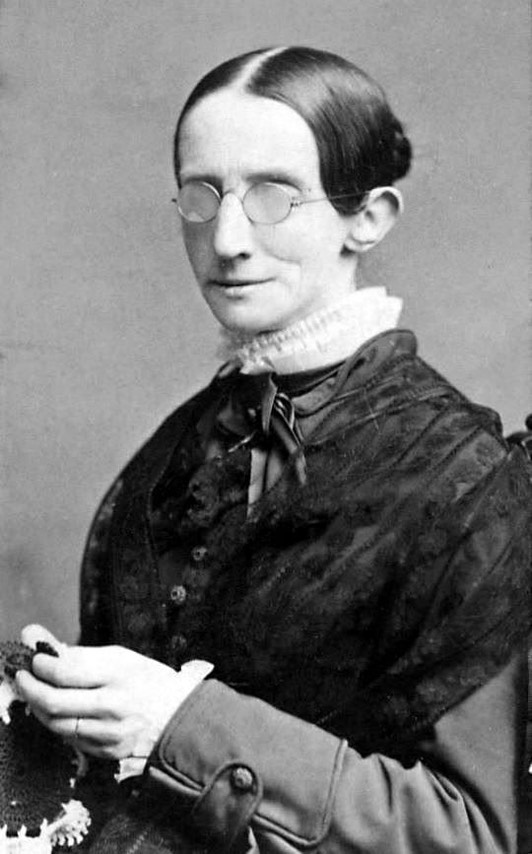

The teacher was born Johanna Mansfield Sullivan on April 14, 1866. Called “Annie” from the time she was a toddler, the playful diminutive gives the impression of a lighthearted optimist, like the other Annie on Broadway, the one who handled a hard-knock life with precocious quips and sassy buoyancy and stopped the show by belting out “Tomorrow.” Annie Sullivan was also an orphan who most definitely lived a hard-knock life, but the similarity ends right there. Annie Sullivan wasn’t lighthearted in the least. Her childhood held no hope for a tomorrow with the promise of sun, even if she had possessed a bottom dollar to bet. Annie Sullivan grew up broke. Annie Sullivan grew up blind.

The poverty resulted from her dirt-poor parents, immigrants from Ireland who came to New England in 1860 to escape famine and settled in Massachusetts where Annie’s dad couldn’t make ends meet, and her mother had Annie and her younger brother. Each pregnancy wilted Alice Sullivan a bit more. Annie’s blindness was likely her parents’ fault too. When she was five or six, Annie came down with trachoma, a vicious infection that resembles conjunctivitis and is caused by sketchy hygiene. Trachoma coarsens the inner eyelid and turns lashes inward. Calling the pain excruciating doesn’t do it justice, and as the cornea scars, the light goes out. Every day brought Annie Sullivan only crippling agony suffered in endless darkness. There was no schooling, so she remained illiterate and unmannered. Her mum died when Annie was eight, and her dad skipped out shortly afterward. She and her brother wound up in a poorhouse where he promptly died. Quite understandably Annie of the truly and unrelenting hard-knock life wasn’t sassy but sullen. The sun wasn’t going to come out for her on any day, ever.

The people running the Tewksbury Almshouse didn’t know what to do with Annie Sullivan, and their puzzlement was all the more touching because of their compassion. They arranged for a couple of operations on her eyes and were crestfallen when Annie remained blind. They taught Annie some basic housekeeping skills in the hope that she could become a scullery maid, but she remained hopeless and withdrawn. Presumably, it could have gone on like that until Annie, like her brother, had just winked out. But an almshouse inspector appeared as if he had stepped out of a Charles Dickens novel. Franklin B. Sanborn paused over Annie Sullivan one day and set into motion the kind of events that move a Dickens plot along. In Annie’s case, Sanborn saw something beyond a sullen little blind girl, all of 14 with sightless eyes shooting daggers. The encounter at Tewksbury was the first piece of the puzzle that would lead to the miracle in Tuscumbia.

Sanborn and others arranged for Annie Sullivan’s admission to the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston. It was October 1880, and at Perkins, the second piece of the puzzle was waiting, even if it took its sweet time to reveal itself. For the time being, though, the Perkins School was miracle enough. It had been founded a half century earlier by Samuel Gridley Howe who revolutionized techniques for teaching the blind. The school took its name from Thomas H. Perkins, a wealthy merchant who lost his sight and donated his home to the charitable cause. The dwelling served as the school’s first property before it moved to more accommodating quarters in south Boston. That was the school’s location when Annie Sullivan came to it, and its pupils by then had become the cosseted children of wealthy parents. Such children were perfectly at home in the comfortable cottages that served as the school’s dormitories. Annie, on the other hand, was overwhelmed by the opulence.

In addition to being overwhelmed, she didn’t fit in with her fellow blind pupils. They snubbed her for her common manners and impenetrable ignorance. Just as bad, some of her teachers were condescending and callous, making her first two years a span of tearful nights and lonely days. Only gradually did sympathetic members of the staff, kind as well as capable people, pet the anger out of Annie. As they softened her rough edges, they put her through rote memory drills, and she slowly picked up the skills that make a blind person’s hand a light on the world.

In fact, after she got over herself, Annie proved a quick pupil, and after she had sloughed off suspicion and distrust, she began to smile in addition to learn. She showed so much progress that the school arranged for two operations that went far in restoring her sight. For Annie Sullivan, it was a gift beyond measure, but as extraordinary as the ability to see was for her, it wasn’t the next piece of the puzzle in the miracle for Helen Keller. That came from an unexpected quarter, and oddly it didn’t just mimic a Dickens plot but indirectly involved Charles Dickens himself, despite his having been dead ten years by the time Annie Sullivan began attending the Perkins School.

At the close of Annie’s time at the school she lived in a cottage with Laura Bridgman. The name means nothing to most people now, and by the time Annie met her, Laura was already a former celebrity who was mostly forgotten. Many years earlier, Charles Dickens had made Laura famous after meeting her during his 1842 travels in the United States. Her ordeal was just the sort of story he specialized in.

Laura had been a sickly infant, but when she was two, scarlet fever made her blind and deaf. She would be that way for the rest of her life. Worse, spending her formative years sightless and speechless resulted in awful physical isolation that scarred her heart and soul the way scarlet fever had ruined her eyes and ears. When she came to the Perkins School in 1837 just weeks before her eighth birthday, she presented an impossible educational challenge bundled into a psychological mess. Dr. Howe’s persistence and innovations broke through seemingly impenetrable barriers by teaching her words from a “manual alphabet” tapped on her palm. Howe taught her language while the kind attentions of other teachers showed Laura love, and by the time Dickens met her, she seemed confident and poised. The author was quite impressed, and he featured Laura Bridgman in a section of his popular book Notes on America that made her America’s sweetheart and sealed the reputation of the Perkins School as the preeminent pioneer in educating the deaf as well as the blind.

Up to a point, Laura’s story was eerily similar to Helen Keller’s. The significant difference in their experiences was to be Annie Sullivan. Annie was to be the author of the real miracle worked in Alabama, but not quite in the way the movie portrays and audiences come away thinking. Here’s a hint: while living with Laura Bridgman, who by then was in her 50s, Annie sensed something troubling. Others before Annie had seen it and were troubled by it too, but Annie recognized it more acutely. In that awareness was the unforeseen key to an exultant ending.

In a story already curious, it became curiouser when Charles Dickens proved instrumental in bringing Annie and Helen together. Kate Keller read about Laura Bridgman in Charles Dickens’s book and persuaded her husband to contact the Perkins School in the hope that a similar “miracle” could be worked for their daughter. By then, Annie was the valedictorian of her graduating class. She stood before the formerly rude children who were now young ladies humbled by someone they had thought common but now knew to be extraordinary. Even as Annie’s address reminded her classmates of the nobility in service to others, Mr. Keller’s letter asking for an incredible service was in the hands of the school’s directors. They put her on a southbound train. She was armed with a thorough knowledge of the manual alphabet and how to teach it, and she carried a doll as a gift. Annie Sullivan was twenty years old.

When she arrived at the Keller home in March 1887, Annie found a wild and uncontrollable child locked in a dark, miserable world. The child’s life was a southern mirror of Laura Bridgman’s, separated by a thousand miles and a half century, but marked by the same affliction of scarlet fever at about the same age that left only darkness and silence in its wake. It was easy to see why nobody had loved Laura when one saw Helen Keller. Grunts and whines passed for communication, and tantrums were frequent. Her reactions were as elemental as those of an amoeba recoiling from pain or clawing frantically to satisfy gross appetites grossly. Helen Keller defied the most persistent attempts at hygiene and was often filthy. She knew nothing resembling hope. She did not love anyone or anything. She was spiteful and selfish, destructive and petulant, and those were her good days. She was terrifying on bad ones, and her family coped with her rather than loved her. Helen Keller was eight years old.

The play and movie get right most of what followed in breaking through into Helen’s world, though the dramatizations don’t adequately show both teacher and pupil as very, very young. Annie eventually insisted that she be given space and leeway to turn a wild animal into a functioning human while teaching her the manual alphabet. She abandoned the strict regimentation of the Perkins method, and most accounts conclude that she did this because of a pragmatic approach to instruction. In that interpretation, it was more important to keep Helen’s attention than to complete lessons. But Annie was working toward something other than focusing Helen on her studies. She was working toward something larger.

For weeks it didn’t seem to matter what she was working toward. Nothing made any difference. Helen remained distant, uncaring, selfish, and unresponsive. At first, she was mildly curious about the stranger tapping on her palm, but Helen soon began snatching her hand away to pout, scream, stomp, and smash. One morning in a fit of rage over the tap-tap-tapping, she broke the little doll the stranger had brought from Boston and giggled in triumph as she felt the stranger calmly sweeping up the pieces around her feet. Helen’s mood brightened when she felt the stranger pushing a bonnet on her head. That always meant going someplace (out of doors) where something warm (sunshine) would bathe her face.

But that morning the stranger would not let her linger. She pulled Helen along a path to a small structure and began the maddening tapping again. Helen was about to jerk her hand away when she felt something cold and wet running over it. The tapping started again. The cold-wet came again. The process was repeated. Helen paused, sensing for the first time a system in the tapping. She cocked her head and squinted her opaque eyes as the cold-wet splashed across her hand. Then the stranger began again. Taps (W) – Taps (A) – Taps (T) – Taps (E) – Taps (R).

And with Helen’s hand gripped by the stranger’s who alternately tapped Helen’s palm and tilted the bucket at the well, it finally happened. Helen Keller “saw” cold-wet and understood that it was water. She realized in a flash that it and everything else, including her, had a name. Later back in her room she ran her hands across the floor in a frantic search for the doll she had broken. The stranger placed Helen’s hands on the pieces, and the little girl, mere minutes after her triumphant breakthrough at the well, began sobbing.

That Helen finally understood the manual alphabet pleased Annie Sullivan, but it was Helen’s tears that made her heart sing. The tears, not the skill, were the miracle. Any competent instructor conversant in the Perkins method and the manual alphabet could with enough patience have taught this little girl the relationship between taps on the palm and the things they represented. Samuel Gridley Howe had done as much for Laura Bridgman fifty years earlier, and the achievement at the time had been hailed a miracle. But Annie Sullivan knew better — or at least, she knew something more.

She knew that despite Laura Bridgman’s ability to communicate, she had remained at the Perkins School as its ward all those years after her “miracle” and in fact would die there. Annie knew from living with her that Laura Bridgman was strangely selfish and unlikable, sour by habit and a puppet of her temper. Laura was never able to function outside the protective cocoon of her benefactors. The people who had freed her had ironically become her jailers because they had concluded that Laura’s flawed personality was the inevitable result of her afflictions. Annie Sullivan wasn’t so sure about that. The little Irish girl who overcame poverty, blindness, and ignorance while enduring the bad manners of her “betters” wasn’t so sure about that at all.

Annie and Helen knew what had happened at the well was important, but they both knew even more certainly that what had happened with the doll was profound. There was still a mountain of work awaiting them that included words to learn and grammar to master, but Helen proved eager and quick, and her skeptical father and protective mother consented to let her go with Annie to Boston to achieve another great cognitive leap, the art of speaking. She came home able to do that. And there, as movie patrons say, is where we came in.

But just a few words more, and they’ll be mainly from the little feral girl who that morning at the well started to become the wondrous creature of poetry, song, wisdom, and knowledge that the world would know as Helen Keller. She would never be a self-imposed captive in a cottage in Boston or a shut-in at Tuscumbia. She would stretch herself to touch with her hands and see with her mind the whole wide world. That was because of the stranger who that fateful morning became “my teacher,” as Helen Keller habitually referred to her closest and most constant friend, Annie Sullivan. It was the way she described Annie for the rest of their lives together. “All the best of me belongs to her,” Helen explained. “There is not a talent, or an aspiration, or a joy in me that has not been awakened by her loving touch.”

On the night of the breakthrough at the well and the miracle of the doll, Helen went to bed a bundle of conflicting emotions. Always before, her bed had been a place only different in degree from other places, a place to rest fitfully until appetites and dreads summoned wakefulness. Wakefulness had always meant a day like yesterday, a day that was always like tomorrow. But that night, Helen lay awake thinking about things with names. Most of all she thought about the stranger who had never done anything but embrace her, even when Helen had broken the little gift proffered at their first meeting. Thinking about the doll made Helen weep again. Later she would understand why.

It was because that night, for the first time in her life, Helen Keller thought about something other than herself. She felt regret for what she had done and sad for someone she had wounded. For the first time in her life, she found herself looking forward to the coming day, in part because she would learn new things, but also because she could begin to make amends for the things she had done.

Annie Sullivan knew from the days of her own darkness and the hours of her own hopelessness what had been the missing key to Laura Bridgman’s prison. It was the path to gladness. For Helen, Annie Sullivan was “my teacher,” giver of light, of love, of language, patient beyond understanding, and the way to “outer things” like Boston and saying “Mama” on a train platform. But Helen also knew that Annie Sullivan was even more. She was the guide to gladness, the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy:

The mountains and hills shall break forth before you into singing

And all the trees of the field shall clap their hands.

Helen put it simply to a friend: “Every day I find out something, which makes me glad.”

The glad, emerging from the tears, was Annie Sullivan’s gift to Helen Keller. The glad made every day a miracle.