The USS Guerriere seemed to be in big trouble. She had put out from Cartagena alone, the other ships of her squadron having already scattered with plans to rendezvous and return to the United States. The weather was fine, but a mild westerly wind was requiring the Guerriere to beat down the Mediterranean on zig-zagging tacks. It was then that her lookout saw the sails of seven warships on the southern horizon. They were coming on hard with all speed to cut into the Guerriere’s course. In what seemed only minutes the ships were identifiable as four frigates and three sloops. Another brief span of time brought them close enough to reveal them as Algerian.

It was curious. As part of a formidable squadron months earlier, the Guerriere had been looking for these ships with the aim of capturing or destroying them, but they had managed to run for Malta; now that the Guerriere was all alone, these ships had come out to find her. The question was, why?

Their approach was menacing, but there was the problem of a new treaty between the Dey of Algiers and the United States, an agreement only weeks old. Any preemptive action by the Guerriere would place blame for breaking the peace on the Americans. Nevertheless, as the Algerian ships formed into what for all the world looked like a line of battle, the Guerriere beat to general quarters, opened her gun ports, and ran out her loaded and primed 24- and 42-pounders. It was then her commander, a commodore, assembled his gunnery crew on the quarterdeck.

“My lads,” he called out, “those fellows are approaching us in a menacing manner.” The crew gazed uneasily at the full sails of the Algerians as they prepared to run past the Guerriere. “We have whipped them into a treaty,” he said, which many may have now regarded as an unfortunate achievement, but the commodore continued. “And if that treaty is to be broken, let them break it.” The crew stirred, itching to get below to the gun decks. The seconds seemed like hours. The first ship in the Algerian line with its guns showing was beginning to draw near the Guerriere. The commodore’s voice became stern: “Be careful of yourselves! Let any man fire without orders at the peril of his life. But let them fire first, if they will.” He then smiled and said, “And we will take the whole of them.”

Well, they thought, that was more like it, more like him, and they returned to their stations reassured but with the precaution of standing back and away from their guns because he had told them to. They would do anything he told them to, even if it meant taking the first punch in what was sure to be a losing fight. But then again, he had said “We will take the whole of them,” and they had reason from experience to believe he could do just that, if the cannons began to bark.

That was because he was Stephen Decatur of the United States Navy. His service to his country was already legendary. And just weeks before this developing incident on the Mediterranean, he had accomplished what the rest of the world had long thought impossible. Stephen Decatur had managed to pacify the Mediterranean Sea.

Decatur came from seafaring people who were commanding ships from French quarterdecks a century before the Decatur clan migrated to the New World. By the time of the American Revolution, the Decaturs were settled in Philadelphia with the patriarch an experienced merchant captain who was soon tapped to command United States fighting ships. While his father was fighting the British, Stephen was born on January 5, 1779, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland because the British occupation of Philadelphia had run his mother out of their home. He was only a few months old before the family returned to Philadelphia. Tradition has it that Stephen at 7 years of age came down with whooping cough, and his father successfully cured it by taking him along on a merchant voyage. More than a cure, the trip sealed the boy’s fascination with the sea. His mother wanted Stephen to become a clergyman, but he would eventually have his way and join the navy. With only the slightest help from his father’s connections, Stephen Decatur became a midshipman aboard the USS United States in 1798. At 19, he was an old midshipman among a cadre whose members could be as young as 12.

Yet, he was a jolly companion and a game compatriot whose advanced age among the boys of his rank never prompted him to arrogance toward them or embarrassment over being in their company. He was quick-witted and applied himself to learning navigation and nautical lore with such diligence that in only months he could sight a sextant, plot a position, and name every function of every hemp line in the confusing tangle of canvas and rope that propelled a sailing man-of-war. “I was struck,” said one captain, “with the peculiarity of Decatur’s manner and appearance, calculated to rivet the eye and engross the attention.” The navy would learn that it didn’t matter whether men were half his age or twice it, whether they were accustomed to tea at Beacon Hill or fisticuffs on the Baltimore waterfront. All would cheerfully follow Stephen Decatur into the most improbable and dangerous situations with a mixture of awe and affection.

Armed with that sort of talent and charisma, Decatur was promoted to lieutenant in only a year and began collecting adventures worthy of Horatio Hornblower and Jack Aubrey combined, with a dash of James Bond thrown in for variety. When he dueled a swaggering chief mate of a merchant ship, dead-eye Decatur aimed only to wound his less skilled opponent. When a boy-midshipman went overboard in a rough sea and others were struggling to lower a rescue boat, Decatur vaulted gracefully over the hammock rail and pulled the choking boy up to cradle him until the boat arrived. When the USS Philadelphia was captured by Barbary Pirates in 1803 and in their hands was an embarrassing symbol of an American mistake as well as serious threat to the United States Navy, Decatur disguised a smaller vessel as a merchant ship and took a tiny but willing crew into heavily defended Tripoli harbor to destroy the Philadelphia at anchor. British admiral Horatio Nelson, the greatest sailor of his time, described the feat as “the most bold and daring act of the Age.” Not bad for a lad of 24.

And to be sure, all of this, including some remarkable exploits during the War of 1812, earned a reputation to be reckoned with. But on top of everything else, in June 1815 Stephen Decatur brought peace to the Mediterranean Sea without paying a penny. It was the first time in centuries that had been the case, and had Nelson been alive, it would have been interesting to hear his judgment of that achievement.

The disturbers of the Mediterranean peace after all had been bedeviling the Royal Navy for decades. In fact, down through the ages pirates ranging out from the North African coast had bedeviled all Europeans, who called the region the Barbary states because of their predominantly Berber populations. Barbary overlords were the provincial governors of the ancient Islamic caliphate that had been inherited by the Ottoman Empire, and by the 1700s their operations had evolved into an extensive and far-ranging enterprise of seizing merchant vessels on the Mediterranean and raiding villages on the Spanish, French, and Italian coasts. Captured merchant crews were imprisoned in Tunis or Tripoli or Algiers, sometimes rotting in cells for years while waiting to be ransomed by their native countries. Everyone was wary about paying ransoms that would surely encourage the taking of more hostages, and Europeans in the main concluded that it was both easier and cheaper to pay “tribute” to the Barbary states than mount expensive expeditions to clean them out. The attitude turned the affair into a shabby protection racket in which the Dey of Algiers or the Bashaw of Tripoli could blithely say, “Nice little merchant fleet you have there. Be a shame if something happened to it.”

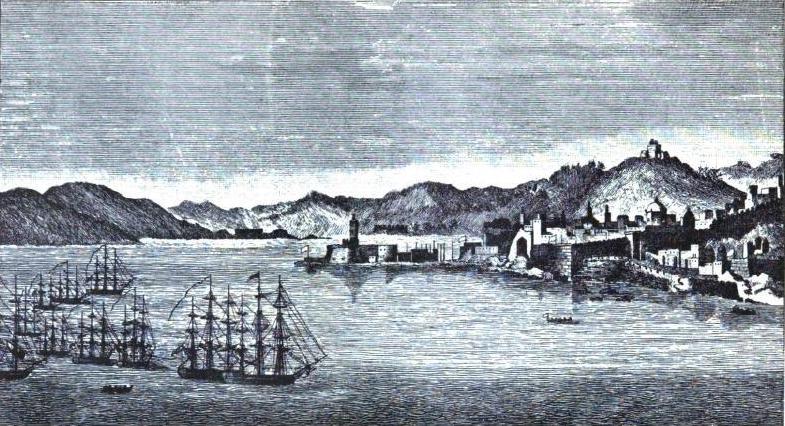

The newly independent United States had grudgingly gone along with the wisdom of paying off the protection racket. Treaties required remittances to the Barbary states, and galling as these agreements were, they worked until the War of 1812. The Dey of Algiers then concluded that the Royal Navy had so humbled and damaged the American navy that it was safe to declare war on the United States and extort a better deal. Instead of buckling, however, President James Madison dispatched a naval squadron to the Mediterranean commanded by William Bainbridge. The squadron included Stephen Decatur, now himself a commodore and commanding USS Guerriere, a fast frigate only a year out from launch. Decatur took his ship and a handful of others through Gibraltar to fight a couple of sharp actions with stragglers from the Algerian fleet. He captured an important frigate and scared the others into Malta. He then sailed to Algiers. He carried a document styled a treaty. But it was really a demand to end the war, stop the piracy, and terminate every penny of “tribute.” Decatur also intended to secure the return of all Christian captives held in Algerian jails.

The Dey’s representative came aboard mildly amused as he imperiously stated terms for negotiations. Decatur said there would be no negotiations. The Dey’s representative insisted that negotiations occur ashore. Decatur repeated that there would be no negotiations and said that any transactions would occur aboard his ship. Startled to see a prisoner from the imposing Algerian frigate Decatur had captured, the Dey’s representative then suggested that an armistice be in force while negotiations were underway. Decatur said there would no armistice because there would be no negotiations. He flatly declared he would sink every Algerian vessel he could find until he had a signed treaty on the terms he had presented. To prove it, he weighed anchor and gave chase to one such Algerian ship that appeared outside the harbor. The Dey’s representative soon reappeared riding a fast skiff to flag down Commodore Decatur and present him with a signed treaty, just as he had dictated. It was June 30, 1815. Decatur was soon greeting freed prisoners They were gaunt, hollow-eyed men who had been wasting away in the prisons of Algiers, some for decades.

From Algiers, he sailed for Tripoli and Tunis with the same purpose and the same results. Hearing who had entered his harbor, the Bashaw of Tripoli recalled the burning of the Philadelphia years earlier and muttered with a hint of alarm, “I know of this man.” By the end of summer, “this man” had forced them all to sign treaties that not only ended the Second Barbary War for the United States but also convinced the British to extract their own set of concessions the following year. The reign of pirates was done, courtesy of Stephen Decatur, USN.

And yet in that fall of 1815 as he was heading for home, his diplomatic and naval triumphs were in the balance before a line of Algerian ships apparently spoiling for a fight. They began passing the Guerriere, pounding through the waves with their gun ports conspicuously open, but they did not open fire. Finally, the flagship bringing up the rear of the line was abreast of the Guerriere and hailed her. “Dove andate?” was the terse query, rendered in Italian, the common linguistic coin of ships on the Mediterranean since Roman times. By its manner, the hail was a belligerent gesture, lacking the customary civility of identifying its ship. It did not frame the question to gather information but sounded like a prelude to withholding permission. The Algerian flagship was demanding to know, “Where are you bound?”

The Guerriere’s sailor with the hailing trumpet glanced nervously at Decatur and thought he saw the hint of a smile. The commodore took the hailing trumpet and lifted it to his mouth. “Dove! Mi! Piaci!” he shouted. The Guerriere’s crew braced. Decatur had responded to the question “Where are you bound?” with an unadorned declaration every bit as crisp: “WHERE! I! LIKE!”

The Algerians pulled in their guns. They, like the Bashaw, “knew of this man,” this Decatur, and they veered off to sail away. That day it was the better part of wisdom to leave this man, his ship, and his country alone.