The errand was solemn, and everyone was silent as the boat glided across the Charles River. They landed and began making their way through the ruins and the barren field pocked with graves. The long British occupation had left a vandal’s legacy, houses stripped of elegant wainscoting for fuel and churches destroyed for sport. They had burned a good deal of Charlestown on the day of the battle and had seen little reason to rebuild a rebel’s lair. The jutting ruins formed a stark backdrop to the men’s search.

Their conversation was terse. It didn’t take long to find the object of their mission, for at least one of them suspected its whereabouts. Their shovels scooped away the earth. Less than three feet down they found a corpse. It had been thrown in with others and was “much corrupted.”

Few markers as to its identity remained. Shreds of a farmer’s frock around the skeletal torso seemed to corroborate stories about how his fine clothes had been stripped off his corpse and replaced with coarse homespun. The silk-fringed garment he had worn into battle had been sold on a Boston street corner by a British soldier. The skull was another clue. Shattered and detached, it had been tossed into the common grave near his remains. Perhaps it was evidence of the sketchy details about a musket ball blowing his head apart, but it could all have been mere coincidence, which meant it was hardly conclusive proof of identity, given the decay.

They all paused and stared. Finally, a stocky, muscular member of the party knelt and gingerly picked up the skull. He turned it in his hand and brought it close to his eyes. He gently put it down. Paul Revere stood up and quietly said, “This is our friend.”

Their friend was Joseph Warren. The name means nothing to most Americans now, which is a sad lapse of historical memory that has become too common in a place whose citizens take their liberty for granted while forgetting the sacrifices that won it. In that shallow grave near the heights outside of Boston lay a fallen hero whose death had shaken Massachusetts to its core. And as the news spread, it had caused men and women throughout all the rebellious colonies to pause, first to weigh the cost of what they were doing, and then to steel themselves to making sure that young Warren’s death would, in the end, help to purchase something decent, noble, and lasting. For Joseph Warren had done more than die for his country. He had died for an idea.

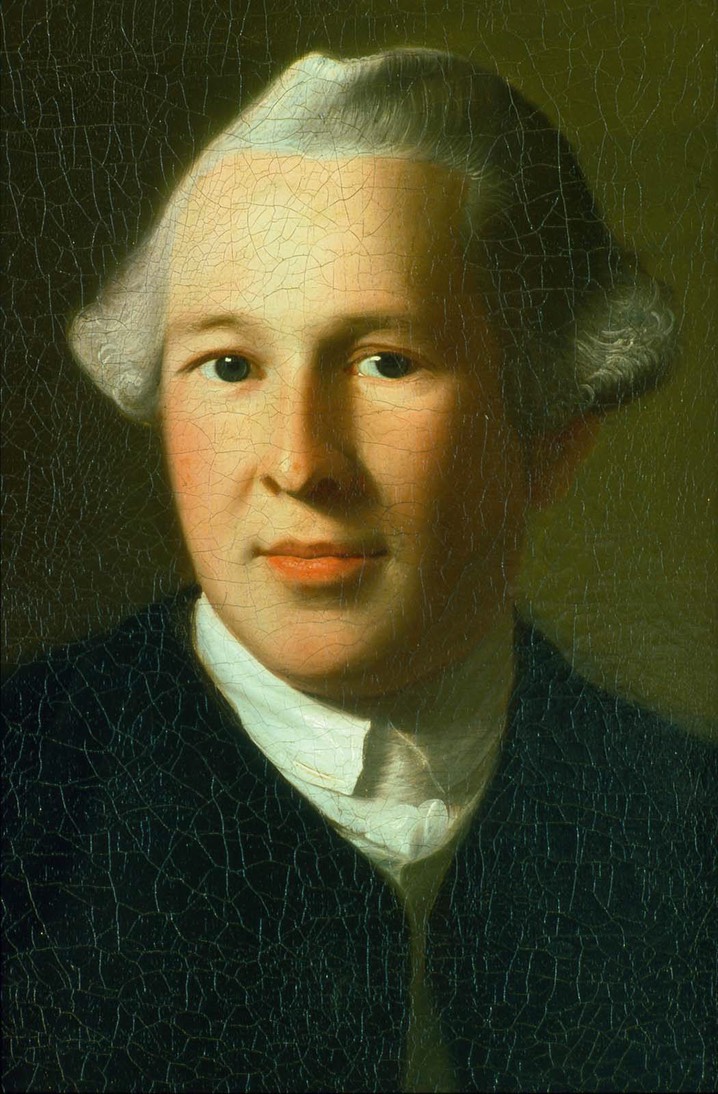

He believed in both the country and the idea with enthusiasm and courage. Warren’s resolve impressed his friends, and his pluck inspired casual companions. Both qualities were evident from his earliest youth. He was a country boy, his father a flinty New England farmer who exhibited the sort of American ingenuity that made places and people better than when found. The elder Warren served his community in municipal offices, supported his church with tithes, and broke stony ground to bring forth food. He experimented with apple hybrids that so improved the succulence of the fruit that his Warren Russet became famous throughout the region. One afternoon, Joseph’s younger brother John was going out to meet their father on his way home from the orchards and instead met his body being carried by friends in a hammock sling. He was dead, his neck broken by a fall from a tall ladder while he was gathering fruit. Young Joseph was fourteen.

His father’s death was proof that life was short and perilous, and Joseph resolved to make something of himself in a hurry. In that, the Warren family exampled a distinctive American type, people who were determined to improve themselves and change the world, even if the “world” was defined as a household or a neighborhood, and bettering it was making a fine apple or in Joseph’s case, making himself a good man his father would be proud of. By the time Joseph graduated from Harvard at age 20, his professors thought him brilliant, and his friends had found him dashing. Having forgotten his key to his dormitory room, he climbed to the roof and scaled down a gutter downspout to enter its open window just as the spout came loose and plummeted several stories to the ground. Dismayed friends knew how his father had died. Warren leaned over the sill to see the fallen spout and chuckled.

To become a physician, Warren sought the most demanding doctor in Boston and spent his apprenticeship “mixing medicines, holding horses, helping ‘make an anatomy,’ tying up slight wounds, or reading Latin books of ‘art medico.’” Barely in his twenties, he opened a practice that thrived because his patients did. His habitual cleanliness struck fellow doctors as eccentric, even obsessive. In addition to a daily bath, Warren washed his hands between seeing patients.

He did not always cure the sick, but he made them no sicker, and he cast his net widely with little regard for a man’s prominence, a woman’s family, or a child’s residence. He set young John Quincy Adams’s broken finger not because his father was a celebrated lawyer. Likewise, he went to Boston’s North End, the place of mechanics and tradesmen because people were just as sick there as they were on Beacon Hill. The house of goldsmith Paul Revere was afflicted with smallpox and under a quarantine flag. Warren came into Revere’s home with the same relaxed poise as when vaulting into the locked dorm room at Harvard. The sight of the young doctor with the light blue eyes and blond hair was good medicine in itself, but his lively disposition and ready wit could make children calm and their mothers joyful. Joseph Warren knew that acting unafraid made others courageous.

Dr. Joseph Warren married a pretty young woman of good family and started a family that would number two sons and two daughters, for everything about the good doctor was balanced and orderly from the routine of washing his hands to the precisely balanced sexes of his children. It would seem to make him an unlikely revolutionary, but all of them were unlikely revolutionaries. British authorities never understood anything about any of them. They could not fathom how Warren could be friends with contemplative James Otis but regard fiery Sam Adams as a political mentor, how he could move effortlessly in the social circle of John Hancock but choose to consort with a common and ill-educated tradesman like Paul Revere.

Warren and Revere were friends, and though he was six years Revere’s junior, Warren was always the dominant figure in their relationship. They were in the same Masonic lodge, and as time went by, they found themselves in accord politically. Warren and Revere bridged the divide of class and status in part because they were good men who saw good in each other. But they also chafed at British snobbery that insulted American colonials while picking their pockets with onerous taxes. Warren used the pseudonym “True Patriot” to protest British policy in the pages of the Boston Gazette, but the British knew he was the author, and his name was on a short list of troublemakers to watch and, if necessary, arrest. “It is certain,” Warren wrote in one of his “True Patriot” pieces, “that men totally abandoned to wickedness can never merit our regard, be their stations ever so high.”

British authorities comforted themselves in the belief that Revere was an oaf and that Warren didn’t have the guts to do anything but mislead his inferiors while writing provocative but empty essays. Nonetheless, Joseph Warren and his friends were engaged in a hazardous business. They risked more than arrest. They faced the prospect of “transportation,” meaning their forcible return to England for trials as traitors before menacing tribunals and hostile juries. One afternoon Warren was walking near the site where public executions of high felons took place: “Go ahead, Warren,” shouted a British soldier in a group with his fellows, “you’ll soon come to the gallows.” Warren wheeled and walked briskly toward them. “Which one of you said that?” he growled. The soldiers flinched and ambled away. “These fellows say we won’t fight,” Warren later told his friends. “By heavens, I hope I shall die up to my knees in blood.”

The chances of that grew greater when British soldiers were transformed from a constabulary to keep the peace into an occupying army to enforce the king’s will and whimsy. Warren sent his friend Paul Revere into the interior on the night of April 18, 1775, on the famous ride to warn John Hancock and Sam Adams that a British force was coming to arrest them. When that force traded gunfire with American militia in Lexington and then Concord, it started the Revolutionary War.

In the weeks that followed, the British made plain their plans to reestablish by force of arms the king’s government in Massachusetts Bay Colony, starting in the environs of Boston. They did not believe that any of the posturing Americans would have the stomach for a droplet of blood, let alone a river around their knees. They were wrong.

Thus, the first full battle of the conflict came to pass on the hills near Charlestown, a fight that would be recalled as Bunker Hill, even though the raw militia and its inexperienced leaders planted their fortifications on another promontory, one subsequently known as Breed’s Hill. On the morning of June 17, 1775, as the British landed in force to march on what they regarded as American rabble, Warren was intent on joining this fight. His resolve alarmed his friends. Elbridge Gerry implored him to stay away from the militia fortifications. Warren quietly quoted the Roman poet Horace: “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.”

For almost an hour and a half, the British army assaulting Breed’s Hill could neither impose its will on the Massachusetts militiamen manning a shaky rail fence nor flank their principal redoubt. In fact, the British were stunned, staggered, and forced to fall back twice. Their third attempt found the militia running out of ammunition, and “a forest of bayonets” stormed the redoubt.

Joseph Warren had placed himself there and was in the hand-to-hand struggle that ensued. He was among the last to quit the place. After a retreat of some sixty yards, he raised his sword to rally the militia when a British officer recognized him, snatched a musket from a soldier, and took aim. The bullet struck Warren in the back of his head. He dropped his sword and reflexively reached for the wound as he fell dead.

Later, the British recognized the corpse and stripped it of Warren’s fine clothes for a farmer’s cloak. They threw Warren into a mass grave, at least until a demented impulse caused them to exhume him to show as a curiosity. Bored with that amusement, they buried him for a final time, and there his remains would rest and decay for nine months. Not until the British occupation ended in March 1776 did Revere, Warren’s brothers, and a few of his friends find him on April 4. They would see to it that Boston gave him a hero’s welcome, a patriot’s proper grave, for all believed that “when he fell, liberty wept.”

Revere had identified his friend by examining his teeth, for among Paul Revere’s many talents was amateur dentistry. When Warren had lost two molars, Revere carved two pieces of ivory and wired them into his friend’s jaw with a delicate silver thread. That April morning, Paul Revere recognized his work and sadly recognized his friend, just as Elbridge Gerry had sadly recognized the provenance as well as the meaning of the sentiment Warren had spoken to him on the morning of June 17, 1775: “It is sweet and becoming to die for one’s country.”

They were not empty words, not for the man who uttered them, the man who heard them, or the people who heard about them as they counted the cost and steeled themselves to paying the price, as Joseph Warren had, and so many have since, for an idea as well as a place. “America must and will be free,” Warren had insisted. “The contest may be severe, the end will be glorious.” He had been twenty-six when he said that, and when he died on Breed’s Hill, he was only thirty-four, an unlikely revolutionary, as they all were. They are worth remembering: Dulce et decorum.