It is a testament to the ingratitude of republics that John Hancock was to lie in an almost unmarked grave for a century after his death. Worse, he fared little better during his life when enemies condemned him for a strutting popinjay whose shallow vanity and vaulting ambition were signs of a weak mind and an irresolute character. They judged his value to the patriot cause as resting solely in his vast and inherited wealth. He was painted as an indifferent revolutionary whose disagreements with British authorities were always over money rather than the ideals of self-government and personal liberty.

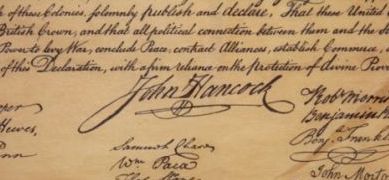

Hancock’s personal habits and behavior were deemed odious. He dressed like a fop, acted liked a peacock, and had a head as empty as his purse was full. He was jealous of George Washington for having become commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, a post Hancock thought should have been his. His signal act of scrawling his over-large and flamboyant signature on the Declaration of Independence was not courageous, said detractors, but a sign of frivolous narcissism.

During the Revolutionary War, they muttered, he deserted his post as president of the Continental Congress to go home to Massachusetts and ply his wealth into popularity. He demagogued himself into a sort of perpetual governorship of the Bay State that was devoid of meaning, except for pandering to the people, and accomplished nothing other than his aggrandizement. It was good, everyone thought, that near the end of his career, Hancock was brought to heel by George Washington, by then the president, and Hancock’s superior in everything, including achievements, office, esteem, and character.

It is quite an indictment. And that is the reason to remember that most of it is not true, and the rest is distorted and misrepresented. Hancock had always been handsome, and he always had money for the finest clothes, the grandest carriages, and the most opulent homes. But the fact that his wealth and his looks were inherited was not his fault. Hancock was neither overly pleasant nor overtly aloof. Though his education never cultivated a great intellect, both were adequate, and though his business acumen was no match for his ancestors, he was a careful steward of the financial empire he inherited, never squandering it, but growing it gradually to about five million pounds sterling (roughly eleven million dollars in today’s money). His foes groundlessly accused him of dishonest dealings to achieve this.

No profound philosophies flowed from Hancock’s pen, and no professional transactions yielded stunning triumphs. He was commonplace in everything but his dashing appearance and gaudy wealth, and his enemies, some of them former friends, some political allies, made him pay for it in ways neither he nor history could have imagined. The patriot John Hancock was to be remembered as merely a disembodied name, the synonym for a signature, or someone somehow connected to a massive insurance-investment corporation that, in fact, he had nothing to do with except for its using his name when founded almost seventy years after his death.

John Hancock regarded George Washington as his friend. When Washington was appointed to head the Continental Army, Hancock as president of the Continental Congress was not jealous but supported the move and the man. Virginian Benjamin Harrison, a friend of Washington’s, described Hancock as “generous” and “noble,” and Hancock told his fellow New Englanders that George Washington was “a fine man.” When Hancock’s only son was born on May 21, 1778, he named him John George Washington Hancock, a boy George Washington never got to meet because Johnny was killed in an ice-skating accident at age eight. The loss devastated Hancock and his wife, who after it remained childless.

Along the way, Hancock’s life in Massachusetts was marked by diligent service selflessly rendered. He led the Massachusetts state constitutional convention in 1780 and became that year the state’s first governor under the document, holding the office almost without interruption until his death. He presided over the state’s ratification convention in 1788, which approved the Constitution by a narrow margin, largely because of Hancock’s support. But also along the way, he alienated former political allies, such as the cousins John and Samuel Adams, whose opposition stemmed from a mixture of jealousy (John) and suspicion (Sam). Hancock also made nationalists, like Alexander Hamilton, mistrustful because they thought his popularity could stoke New England localism and harm the federal union.

Whether they were right or wrong about this, they had George Washington’s ear, and that was one of the reasons John Hancock found himself in the middle of a controversy with Washington, the one that was supposed to have taught the governor of Massachusetts a thing or two about who he was and, more importantly, how he should treat the President of the United States. It happened in the fall of 1789 during Washington’s first journey as president. The incident set the protocol that made the President of the United States superior to state governors. That outcome is universally applauded as fortunate and appropriate.

George Washington did not usually meditate on political philosophy, but he knew that status and pride were inescapable parts of political life. It was the reason that when he became the first president under the constitutional system in 1789, he confronted a set of thorny problems. Everything about the government and the federal union was new and untested. There were questions about the loyalty of those who had opposed the new Constitution as it was being written and ratified. Navigating this uncharted ground, Washington had to find the exact path between the two poles of liberty and authority. It was the age-old question of ensuring that liberty did not become license while making government effective but limited.

A complication in striking that balance was the dilemma of the Constitution itself. It had created the federal government in part to transcend local interests that could be divisive and contrary. But the Constitution’s success depended on the cooperation of states touchy about their sovereignty and jealous of their power. Framed that way, the issue was practical rather than philosophical, and Washington understood it perfectly in those terms. It was the reason that, as president, he traveled.

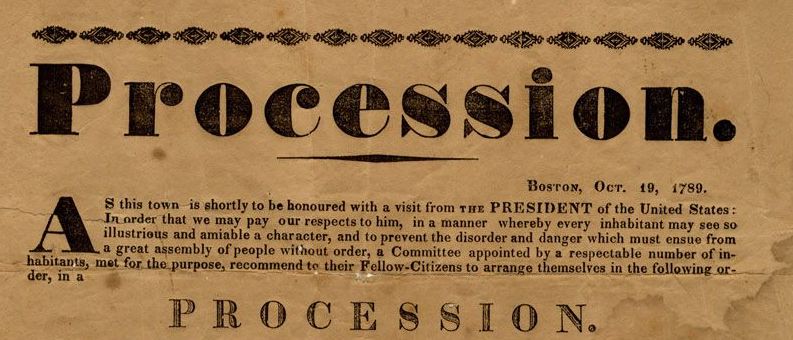

His trip to New England in the fall of 1789 was ostensibly to visit scenes of the revolution and enjoy the company of fellow patriots in hearty reminiscences. But the journey was actually meant to test the strength of the new federal union in the seedbed of the revolution that had made it possible. The warmth, or chilliness, of New Englanders would reveal how effectively Washington’s reputation could encourage support for the federal experiment and blunt touchy regionalism.

On the morning of October 15, 1789, President George Washington and a small entourage left the capital in New York City and headed for Boston for a week’s stay. The journey was heartening as crowds in towns along the way cheered themselves hoarse. Vice President John Adams ventured ahead to Boston to make sure everything was prepared for the president’s arrival, and the people of the city were near bursting with excitement by the time he arrived. Throngs shoved and necks craned to catch a glimpse of him. Daily festivities promised to be tiring, but they were also propitious, and friends of the president judged the visit a success before it had even begun.

Nobody should have been surprised by these events. Washington was spectacularly popular in 1789, universally regarded as impeccably honorable, selfless and self-effacing, towering in personal majesty but refreshing in his lack of worldly ambition. He had defeated the greatest empire on earth with a ragtag army and an iron will and then had put down his sword and retired to his home. He answered the call of his country to serve in the presidency, but he was acceptable to the country precisely because of his reluctance to take the office.

But for all that, there were citizens troubled by the veneration of Washington the president as much as they were enthusiastic about the celebration of Washington the man. There is nothing to indicate John Hancock was among them, but he became both a symbol of their misgivings and a warning about the potential consequences of voicing them.

Here is how that happened. Governor Hancock had invited the presidential party to attend a celebratory dinner at his home as a welcome to the city, and Washington had gladly accepted. However, when the president arrived on Boston Neck, the governor was not there. The day was cold and drizzly, and Washington curtly asked if there was another way into Boston. Told there was not, he nearly canceled his visit on the spot but relented when made to realize that the city fathers and a large gathering were waiting for him. His entrance was triumphal as always, but at the Statehouse, the set of his jaw showed he was still upset. He expected Hancock to visit his lodgings, but the governor did not come, and for Washington, the omission became impossible to overlook.

Why? Well, it’s usually explained that President Washington meant to outrank Governor Hancock, not out of personal vanity, but because of the precedent it would set. Establishing that protocol required Hancock’s symbolic submission, not as John Hancock, but as the governor of Massachusetts. In that role, he was expected to visit the Chief Executive first.

When a note arrived from Hancock explaining that his health would not permit him to go to Washington’s rooms in advance of the planned dinner, the president perceived a ploy to establish a state governor as the president’s equal. Why he thought this is anyone’s guess, but it’s worth remembering that he was primed to the purpose of the journey, which was to test New England loyalty. In that, his advisors had likely warned him to be vigilant about slights to his office as symbolizing slights to the federal union.

Perhaps that is why he responded to Hancock with a note of his own, decidedly chilly in temper: if the governor was too ill to visit the president, he must be too ill to entertain him. Washington remained at the inn and had a quiet supper with John Adams.

Alexander Hamilton would have rejoiced over this insistence of subordinating a state to federal authority, and, as we mentioned, Washington’s behavior is usually lauded as appropriate. Yet, we might also surmise that the matter was more complicated than that, and to his credit, George Washington eventually realized this.

In the first place, Hancock was telling the truth about being sick. Severe gout had plagued him for years, and chronic illness had worn down both body and spirit, making the once-striking man a shadow of his former self. Dinner guests pitied his appearance and looked away from the wheelchair that forced him to eat at a small separate table.

On the day Washington arrived in Boston, the weather was abysmal, and the damp cold caused Hancock to suffer more than usual. He likely did not appear at Boston Neck because he could not, and he probably thought nothing about staying in and waiting for Washington to come to dinner. The president would have been accorded every respect due his office. He would have sat at the main table with all the important guests while a servant pushed Hancock to the makeshift one, apart.

Yet, something else was happening here, and the two principals found themselves unwittingly caught up in it. The eagerness to make the federal government supreme, even to the point of eliminating state sovereignty, had motivated some instigators of the Constitutional Convention. It was a position that Alexander Hamilton surprisingly shared with James Madison at the time, though Madison would gradually change his mind. Yet in 1789, with the Constitution and the government it had created only months old, nationalists believed that the point about federal supremacy should be made, and where better to make it than in the New England state that had shown itself reluctant to ratify the Constitution? And who better to make the foil for Washington’s deserved majesty, imparted to the presidency, than a man assiduously depicted as vain, ambitious, and jealous — a man who happened to be the governor?

Alexander Hamilton was among those who believed European veneration of monarchs was a healthy expression of political and spiritual unity, something that could be adapted to the American setting. Old World celebrations that hailed royal births, coronations, and kings’ birthdays were soon being mimicked in regard to George Washington. His birthday would resemble a national holiday with balls and concerts in his honor. Devotees of republican government wondered about the wholesomeness of these practices. Veneration held dangers that transcended constitutional limitations on presidential power, and real worries arose that not Washington, but his closest associates, were nudging the nation toward monarchy.

In that setting, those who condemned John Hancock’s behavior as disrespectful to the president could exploit a curious confusion. Did the people of Boston grumble about Hancock’s behavior because George Washington was the president or because he was George Washington? The answer to that question vindicated a considerable number of people in the shadows who were concerned about the future of the republic. For them, the President of the United States should be treated as a fellow citizen who had been given temporary (and limited) powers to administer the republic’s laws. Just months after the adoption the Constitution, though, and with the office of president less than a year old, it seemed to be taking on the trappings of something troubling and even potentially hideous. It was a fearful prospect, especially if hidden by the glow of a great man.

Washington finally seems to have realized that he and Hancock were victims of a misunderstanding caused by these hopes and fears. His chilly note sent a spear of pain through Hancock worse than the gout’s, and the next day, the governor asked if he could call on the president. Washington coldly advised that he had about an hour free in the early afternoon, but he would be engaged after that. Hancock was at Washington’s door in thirty minutes. When servants carried Hancock inside, Washington was stunned by his wretched appearance. He had not seen John Hancock since the Revolution. The handsome patriot with the flourishing signature who George Washington remembered from the glory days of the Declaration was no more. He had become a gnarled shell with bloated limbs wrapped in red flannel.

George Washington seems to have instantly stopped thinking of himself as the president. He dropped his curt manner. It was as if a great revelation flashed through his mind and touched his heart. Was John Hancock’s behavior simply a lamentable result of sickness and frailty? For whatever reason, Washington seems to have suddenly looked beyond the shrunken old man who had been brought to his rooms and again gazed on the “noble” and “generous” fellow patriot from those days when it was dangerous to be one. Hancock had called George Washington “a good man” and had named his son after him. There are reasons for a man to say such things, to do such things, and vanity and ambition are not among them.

John Hancock died almost exactly four years to the day after that fateful week. He was only 56, firm proof of his declining health. It is sad that he is defined by an episode whose meaning was possibly bent to a purpose and consequently could have been misunderstood. The story always describes Hancock snubbing Washington out of a mixture of jealousy and pride, but it deserves a deeper meditation, just as Hancock himself deserved the benefit of the doubt when Washington saw him that morning. Hancock’s fellow patriot, who happened to be the president, relented. History should be willing to do at least as much.