This year, to celebrate George Washington’s birthday, we travel back to his youth when Virginia’s colonial governor Robert Dinwiddie sent him into the trackless Ohio Country. Washington was a mature but untested 21-year-old who found himself on an impossible mission.

He was to deliver an eviction notice to French interlopers who were trailing down from Canada to build forts and court Indian allies. Nobody knew it in 1753, but these activities set the stage for a vast global war between the superpowers of that day, Great Britain and France. The contest for imperial supremacy that stretched from the Indian subcontinent to the threshold of Québec and southwestward to the Ohio wilderness would be called the French and Indian War by Americans and the Seven Years’ War by Europeans. Historian Lawrence Henry Gipson more accurately labeled it “The Great War for Empire.”

The prelude to this epic clash had George Washington assembling a small party of seven men, mostly “servitors,” as Washington referred to them, to manage horses and equipment. Washington could not speak or understand French, so he enlisted an interpreter. But his most fortunate addition was a guide named Christopher Gist. He would be at Washington’s side for the entire roundtrip journey of some 500 miles.

The first part took them nearly to Lake Erie’s shores. The second returned them home, but only barely. In all, the expedition consumed ten weeks, the most grueling portion of it the trek back to Virginia as Washington and Gist tried to claw their way through awful winter weather and nearly lethal misadventures. Gist was a grizzled character in buck-skins straight out of central casting who, like the best of guides, knew something about finding one’s way in an abstract as well as a material sense. His lessons were about more than woods lore and Indian relations. They were about the essentials of life and death, and the value of promises.

With curly black hair, a full beard, a thin face, and prominent eyebrows, Christopher Gist looked every bit the weathered pioneer, the kind of man who licked his thumb to clean gun sights for improved accuracy. Gist occasionally worked as a scout for the Ohio Company, a group of Virginians who planned to survey and sell the western wilderness that the French were co-opting, so he knew the land where they were going better than any white man in the world.

He was in his mid-forties when Washington met him and had already done enough living for several men. Indeed, he was a bundle of quiet fortitude and subtle surprises, such as his habit of keeping a journal of laconic entries that always balanced bad news with good cheer. It was the part of Gist’s manner that made him easy to like, but it was his sense of virtue that made him easy to trust. He was indispensable for daily necessities, such as bagging game for a night’s rations, but he was more than a skilled hunter with a good sense of direction. In a crisis, Gist was steady. Stoic and seemingly passive, he had a matchless knowledge of how to stay alive in a place where almost everything was trying to kill you, but he rarely gave unsolicited advice. If a man wanted to pick up a cat by its tail, Gist let him. The experience was a better teacher than an argument. He treated Washington this way, which suited the young man who liked to work things out for himself. At the same time, Gist taught Washington by example how to survive in an unforgiving world and how to get along with the people living in it.

This last was crucial to their mission. The Indians always trusted Gist because he had never lied to them and always treated them fairly. He kept his broad mouth shut about how they lived and kept it free of sneers when he accepted their hospitality. He resigned himself to their occasionally ferocious customs — he once wordlessly watched a captive Indian woman tortured to death — but he often found them more personable than some of the unruly whites who wandered the frontier.

Gist probably understood better than Washington that visiting the French was an excuse for the real purpose of the journey, which was to renew contact with Indians. They were the key to everything in a place with no European armies but only small garrisons of a few dozen men with muskets and, if they were lucky, a few field pieces. The Indians were the populace of this wilderness, able to instantly melt into the woods and silently reassemble just as quickly to decide battles and win wars. Gist tried to teach Washington this reality as he was leading the way to Fort Le Boeuf, and some of it took, some of it didn’t.

Washington had known Indians all his life, but those of his childhood were only the shadows of their frontier counterparts. He first saw Indians as creatures of the forest during a 1748 surveying trip in western Virginia, and it had been an eye-opening experience. Five years later, persuading these people that the British were still a presence in the region was imperative, and Gist could help him do this too. Without the aid of the Indians, everything else would be in jeopardy. As Washington’s expedition trekked northward, Gist arranged a meeting with the most consequential Indian he knew.

He was an Oneida/Seneca named Tanacharison, whom the British called the Half-King, the leader of the Mingoes, fierce Iroquoian people who could cover miles in deep snow and fight to the death afterward. The Half-King was in his early fifties, at the height of his influence, and one of the few friends the British still had as the French came with lavish gifts and tempting promises. The Half-King was a shrewd judge of men, and he had no illusions about Europeans. He knew that British friendship was opportunistic rather than affectionate, but he sincerely hated the French because they had kidnapped him and killed his father. That the French had also eaten his father, as the Half-King claimed, was undoubtedly an exaggeration, but his encounter with swaggering, contemptuous French officers remained a gnawing memory. This proud man deeply resented insults.

His meeting with Washington went well. The tall Virginian made the obligatory speeches voicing the proper sentiments while cutting a striking figure. Gist knew this would work. They lingered at the Half-King’s village longer than Washington wanted, but Gist likely told him that a hasty departure would be rude. Washington thus learned much more than a brief acquaintance would have shown him. The Half-King was a good friend. Later, Washington would see that he could be a horrifying enemy.

The Half-King went part of the way with Washington as he continued his trek north and even provided a small escort to accompany him to Fort Le Boeuf. However, the young Virginian marked these gestures as a mixed blessing, for his small group was anything but impressive, and he rightly feared that the French would seem more imposing to wavering Indians. In any case, at Le Boeuf, he discovered they were on a fool’s errand.

The French commander was pleasant but blunt in his response to Governor Robert Dinwiddie’s demand that the French leave British territory. It was as everyone should have expected, and the Englishmen spent their three days at Le Boeuf taking stock of the garrison and its firepower. The French did not mind. There was no British army to fear, certainly not the Virginia militia, and odds were that Washington and his companions would not survive their journey home. As it happened, this last prediction was very nearly correct.

The trip back, begun in mid-December, became a nightmare as icy rain pelted and drenched the men. They marveled over creeks that first fell fast then froze over. It snowed heavily to make gloomy forests doubly dark while blocking meadows with impenetrable drifts. Men and horses flagged, and Gist for once broke his rule about advice and pleaded with Washington not to abandon either of them. But Washington was acutely worried that the French were rapidly solidifying their hold on the Indians and their claim on the region. Every hour he let pass without letting his superiors in Virginia know about this situation was a gross and costly dereliction.

He therefore hatched a plan. He and Gist would leave the rest of the party in shelters where they and the spent horses could wait for better weather and improved health before resuming travel. Gist flatly observed that they would sorely miss the horses in only a few hours, but he also saw in the set of young Washington’s jaw a man reaching for a cat’s tail. The old frontiersman pulled down his hat, put up his collar, and said nothing more.

Within hours, Washington discovered that Gist had been correct and was likely grateful that the old fellow was kind enough not to mention it as they both suffered increasing agony plodding across uneven terrain. Perseverance and sheer grit saw them reaching a small outpost where a bit of nourishment and a crackling fire renewed Washington’s resolve to press on. Gist did not object, and he even consented when Washington enlisted an Indian guide to help them find a shorter route to an Allegheny River crossing.

The Indian claimed to know Gist, but he was lying, and following him was a grave mistake. He became surly as he traced a route that made Gist increasingly suspicious, a feeling confirmed when the Indian tried to kill them. His bad aim saved them, but Washington’s mercy saved the Indian. Gist wanted to execute him on the spot, but Washington decided that they should get away from him. Gist consented, even though it meant the extra burden of time-consuming tricks to cover their tracks.

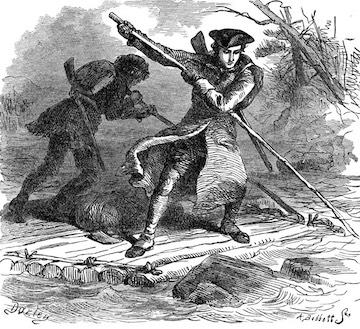

When they reached the Allegheny River, they were dismayed that it was the only watercourse in the region that was not frozen. Instead, they found it running so hard that they had to cobble together a log raft and try to pole themselves across the frothing water. The turbulence and racing floes tossed Washington from the raft into the icy torrent, where he almost drowned before Gist helped him scramble back to safety. They barely made it to an island in the middle of the river, where they spent a night so cold that the Allegheny had frozen over by morning. Gist suffered frostbite, but Washington was miraculously unharmed, a bit of luck that continued when they found they could walk on the ice to the opposite bank and continue their journey.

The worst was over, except for the tedium of distance and the exhaustion of covering it on foot. When they reached the Maryland frontier, Gist stopped, for it was where he had begun, and his farewell to Washington, who was continuing to Williamsburg, was likely casual, as if they had been on a picnic. Gist always balanced bad memories with good cheer, the way he made entries in his journal.

Washington survived this impossible expedition because of several fortunate instances, such as surviving a treacherous Indian’s attempt at murder. But he was more than lucky to have Christopher Gist as a guide. His association with this admirable man would continue over the next five years while they fought the French and their Indian allies for the Ohio Country. Gist joined the fray as a captain in the Virginia militia and remained one throughout. Distinguished among the officers for likely saving Washington’s life, he never talked about it. Instead, he served in a lowly rank with meager pay under demanding conditions without complaint. He always stood quietly by, and when needed, he stood fast.

When Washington had started the trip into the Ohio Country in that autumn of 1753, a messenger had brought word that Gist’s son was very ill and needed him. He naturally wanted to go back, but he had promised that he would take Washington to Fort Le Boeuf. Gist hastily put together a bundle of herbal medicine and sent the Indian back with it. He would not leave the young Virginian’s side either at the outset of the journey or its grueling conclusion. In a place where almost everything was trying to kill you, promises had to mean something.

By example, it was Christopher Gist’s best lesson of all. That one took completely.