The folksy backwoods character Americans know as “Davy Crockett” was born on August 17, two hundred thirty-four years ago. For much of the two centuries since then he has been a staple of the entertainment industry, making the Crockett franchise one of the longest-running shows in American history. Even as the real person named David Crockett lived, publishers were producing adventure tales disguised as bona fide biographies, and almanacs filled with Crockett’s common sense and comical sayings became annual bestsellers. His death at the Alamo in March 1836 only increased his celebrity and, accordingly, his marketability. In the years leading up to the Civil War and in the decades after it, biographies continued to appear. And though some were a bit more discerning than the press-agent puffery of those Crockett had a hand in, they were still mainly laudatory with Crockett a manly hero full of frontier sass and vinegar, a superb marksman and a witty raconteur.

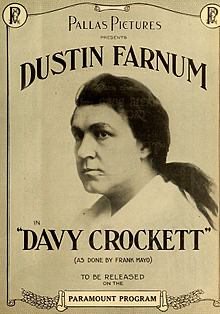

In the first decade of the 20th century when motion pictures were in their infancy, Crockett hit the silver screen in four silent features in which he was portrayed by famous stage actors such as Charles French and the delightfully named Hobart Bosworth, a matinée idol who could trace his lineage to the Mayflower. In 1916, a movie star of the first order named Dustin Farnum played him, and when talkies came on the scene, they were soon adding more adventure stories to the Crockett oeuvre. In the late 1930s, composer Kurt Weill even toyed with the idea of putting Crockett’s story to music in the style of his Three-Penny Opera. “Mac the Knife” could have been joined by “Davy the Gun.”

It was in the mid-1950s, though, that something unexpected happened to the well-worn Crockett warrant. It only took three measly one-hour television episodes to prove the power of the new medium over its rival radio while burning “Davy Crockett” into the annals of American entertainment as a cultural phenomenon. Twenty-nine-year-old Fess Parker was the eleventh actor to portray Crockett, making him rather late to the party, but there was something — the timing or the stories or some other intangible thing — that produced a storm of popularity that caught everyone by surprise, including the founder of the feast, Walt Disney. Mr. Disney, as Parker always called him, had only wanted a rousing but unassuming adventure tale to help promote the new theme park he was building called Disneyland. Mr. Disney instead stumbled on a gold mine.

People everywhere whistled the show’s theme song, a catchy tune that opened with the lyrics:

Born on a mountain top in Tennessee,

Greenest state in the land of the free.

Raised in the woods so’s he knew every tree,

Killed him a bear when he was only three.

Followed by the kicker of a chorus — Davy, Davy Crockett King of the Wild Frontier — a phrase adapted to the subject of succeeding stanzas about fighting Indians (the man who don’t know fear), going to Congress and patching up the crack in the Liberty Bell (seein’ his duty clear), or heading off to Texas (leadin’ the pioneer).

Factories couldn’t churn out the toys fast enough, and boys all over the world were soon on waiting lists for little long rifles and metal models of the Alamo with plastic Mexican soldiers and plucky Texans in various fighting poses. But it was Davy Crockett’s signature coonskin cap that became the item of choice, the merchandiser’s brass ring, the emblem that was instantly recognizable and served as the ubiquitous advertisement for everything else about the Crockett franchise. Every kid wanted a coonskin cap, and millions got what they wanted. In A Christmas Story, Ralphie’s nemesis Scut Farkus wears a coonskin cap.

Fess Parker always liked the role and never complained that it more or less typecast him for the rest of his career. Unlike many nice looking lads plucked from the obscurity of B-pictures, he never resented the source of his success, and in that he was rather like the man he portrayed. In the 1820s, David Crockett was a nice looking lad plucked from the obscurity of the frontier, and far from objecting to the image that more or less defined his public personna, he eagerly participated in its formation and maintenance.

Because of that, the real David Crockett wasn’t a victim of the mid-20th century marketing frenzy that seemingly lost him in the shuffle of colorful trading cards. The real David Crockett was just as hard to define while he was alive and, thus, even more so in retrospect. It is, in the end, the old story of separating fact from fiction, of distinguishing folklore from reality. In that quest, historians have analyzed and assessed Crockett from almost every angle to conclude that the man the public knew was a caricature at best, a fraud most likely. Those who embrace this interpretation scoff at him as a failure at everything but self-promotion. They recall Alexis de Tocqueville’s marveling over the ignorant and impoverished Crockett’s unlikely rise to a seat in Congress by his defeating “a man of wealth and talent.”

Crockett had no talent, conclude these assessments, but was shaped by “promoters” into an idealized backwoodsman for marketing purposes only slightly different from Walt Disney’s. In this interpretation, heavily larded “biographies” painted him as self-made and confident to mirror fictional romantic characters made popular by James Fenimore Cooper’s novels. If this is true, Crockett’s acclaim stemmed exclusively from a deliberate design to manufacture a man around a name. Opponents of Andrew Jackson ginned up the scheme to use a frontiersman in Jackson’s own image as the anti-Jackson. The fact that he was from Tennessee was a bonus.

To be sure, people who want to make Crockett into anything their interpretation requires have some rich material to work with. He wasn’t born on a mountaintop in Tennessee but on Limestone Creek off the Nolichucky River on August 17, 1786, to a life worse than humble. The Crocketts were hardscrabble pioneers stalked by want and deprivation. His mother was nondescript, and his father was a ne’er-do-well and angry about it, indenturing his children to more prosperous neighbors for the extra cash they could bring in. He disowned his oldest child, a daughter who was molested by her master and who died giving birth to the baby. David, who was never “Davy” except in the romantic literature, muddled through, himself indentured for a time, before knocking about the country while learning about life everywhere but in a school.

Perhaps because there was no “family” for little David Crockett in the traditional sense, he was fiercely determined to have one of his own when he grew up. At 20, he married and started a family while trying to start a farm, but the family grew as the farm failed, and he turned to hunting — elk and mostly bear — for food and the money that skins would bring. He was on the face of it no different, no worse, nor any better than any other frontier folk who subsisted in the hard world of smoked meat, rude cabins, and children dressed in pelts. When Thomas Hobbes talked about life as “nasty, brutish, and short,” he defined these people perfectly.

Yet the evidence indicates that David Crockett was different. People always liked him, even before there was any hint of image building by outside managers. He was blunt and honest and could be fun as well as funny, willing to sling a jug into the crook of his arm and pull on it with the most hollow-legged companions. There isn’t a single instance on record of his picking a fight or running away from one. He never flaunted his courage, but it was frequently on quiet display. He served in the Creek War of 1814 and afterward in the closing months of War of 1812, both times under Andrew Jackson, and rose to the rank of sergeant.

He later was elected a colonel in a militia company and wore the honorary title for the rest of his life, a custom of the time. Crockett’s colonelcy is vital in proving his popularity. It landed him in other offices as well: he served two terms in the Tennessee legislature, and after a failed bid in 1825, he won a seat in the United States House of Representatives in 1827. He supported Andrew Jackson, but that would change when Crockett disregarded all counsel for caution and broke ranks to denounce Jackson’s plans for Indian removal as “wicked and unjust.”

All of it, including his opposition to Jackson, tells us even more. David Crockett was not just popular. He was trusted, and in his world, trust was the highest compliment a neighbor could bestow. No manager could purchase it, and no manufactured image could secure it. Not a soul could recall his telling a lie at another man’s expense, and his exaggerations about himself were the stuff of frontier slang and parodies of the folk tale boast.

“I am,” he would announce to a tavern of astonished tipplers, “that David Crockett, fresh from the backwoods, half horse, half alligator, a little touched with the snapping turtle.”

Their laughter encouraged him. “I can wade the Mississippi, leap the Ohio, ride upon a streak of lightning, and slip without a scratch down a honey locust.”

Their cheers egged him on. “I can whip my weight in wildcats, and if any gentleman pleases, for a ten-dollar bill he can throw in a panther.”

A man who could riff like that on the frontier didn’t need to buy whiskey to win elections. Crockett won them despite his poverty in everything but talk — and honesty, when it counted. He was a jovial fellow with a ready smile and laughing eyes who would take a heap of joshing, which meant his friends were numerous and loyal. “I reckon nobody in this world loves a friend better than me,” he chuckled, “or remembers a kindness longer.” That said, it was also clear that Crockett drew a line over a snide insult. A man foolish enough to cross that line would wipe away the smile and put the eyes into a dark squint, the prelude to Colonel Crockett beating the hell out of him and any of his friends, six ways from Sunday.

He became a curiosity in the staid salons of the East, and inevitably hyperbole stitched the seams of his biographies. He didn’t mind. It was part of the fun when stories circulated that the government had hired him to snatch off a comet’s tail or he had fled a tornado by jumping on a bolt of lighting. That was how he took rank with other folk characters of the tall story, a staple of American lore that included swaggering boatman Mike Fink, steel-driving John Henry, and tarnation-invoking Pecos Bill.

“Davy Crockett” symbolized the America of the fantastic boast. But Colonel David Crockett was another creature entirely. He skewered Congress while sitting in it. Congressional investigations reminded him of a stupid bear hunter who always looked for his quarry where he had been, rather than where he would go. And he ruined his political career by denouncing Andrew Jackson as a petty tyrant, a show of courage that was more than show. It revealed a deep and resolute virtue. “I’d rather be politically damned,” Crockett muttered, “than hypocritically immortalized.”

Even given all this, it would be easy to dismiss all the good and sound words about virtue, friendship, honesty, and integrity as simply part of a manufactured mix considerably alloyed by the boastful and deceitful stories of grabbing comets’ tails and vaulting over major waterways. The mix might very well muddy the truth by obscuring the real Crockett, who was nothing more than a celebrity fraud, a con man, a huckster with a marginally entertaining line of patter.

It would be easier to conclude this — if it weren’t for Texas. Every critic, every scoffer, every cynic draws up short when it comes to Colonel Crockett at the end, because leopards don’t change spots and cowards don’t suddenly sprout courage. When the Jacksonians were able to defeat Crockett at the ballot box, he famously told his constituents that they could go to hell, but he was going to Texas. That was how he came to the little mission at San Antonio de Bexar where he would die. Not only did he not have to go to the Alamo but once there he didn’t have to stay. But he did go, and he did stay in the face of certain death, and explaining that within the claim that David Crockett was a manufactured man is a pretty hard trick.

Walt Disney’s third episode was about Crockett at the Alamo. In it, he does not die. Out of ammunition, Fess Parker is being attacked on all sides by an overwhelming surge of Mexican soldiers, and the final scene fades out with him still standing, swinging the long rifle he called “old Betsey.”

Possibly it happened that way, but even if it didn’t, Colonel Crockett would like that way of telling it. He once visited a Philadelphia zoo and saw a monkey that he said would resemble a political opponent “if the keeper of the varmint would place a pair of spectacles” on it. When he was called out for the offensive comparison, David Crockett apologized. To the monkey.

A man like that lives forever. He is after all the star of the longest running show in American history.