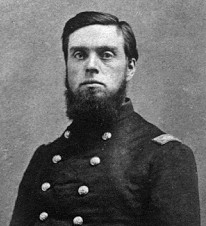

Colonel John T. Wilder had reason to be uneasy, but not, as has often been reported, because he didn’t know what he was doing. True, he had been a mere private at the start of the Civil War when he impulsively left his Indiana foundry at the age of 31 to enlist in an artillery battery. His almost instant promotion to captain was through election by his fellows rather than any military experience. Similarly, the governor of Indiana had prematurely made him a lieutenant colonel in the 17th Indiana Infantry only weeks after that. Wilder’s was the sort of spectacular rise that happened all too often in the early months of the war when political influence often had more weight than military achievement. Wilder, however, soon “saw the elephant” in sharp little actions in western Virginia, and at the end of 1861, he became part of Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. That meant he was at Shiloh on the second day. At that battle, he received a military education in hours that had the value of years.

So, John Wilder wasn’t a chocolate soldier. Instead, he was courageous and resourceful. When given command of a mounted brigade in 1862, he worked the system like a veteran to equip it with Spencer repeating rifles. And when he landed at Munfordville, Kentucky, with the job of protecting a vital railroad bridge on the Green River, his men admired his judgment and liked his fairness. For a time, all seemed well, even though Confederate forces unexpectedly marched into Kentucky. The development, however, prompted Wilder’s superiors to send a more experienced man to assume command. Wilder wasn’t vexed. Indeed, he was relieved when Col. Cyrus Dunham showed up with a higher rank and more experience. The 4000-man Union force had a strong position and good leaders in Dunham and Wilder, and when Confederate advance units of Braxton Bragg’s army began poking about, they easily repulsed them.

Then everything abruptly changed. Bragg had not planned to fight at Munfordville, but the thing having started there, he resolved to finish it by bringing his army of 25,000 men to the little town and crushing its defenders. Sensing the different situation, Col. Dunham told his superiors he would surrender if not reinforced. They responded by replacing him with Wilder.

Amid these rapidly unfolding and troubling developments, Wilder had hints that Dunham was on to something about needing reinforcements. A massive Confederate host was surrounding Munfordville. Messages from that army began arriving, demanding his surrender to prevent needless bloodshed. “If you wish to avoid further bloodshed,” Wilder pluckily replied, “keep out of the way of my guns.”

Wilder was whistling his way past the graveyard, but privately he was profoundly worried about the fate of his 4,000 officers and men. More than six times their number surrounded them at a place they were ordered to protect. John Wilder read and re-read the Confederate ultimatum to surrender that night or fight on the morrow. He was ready to die, but then it occurred to him to take an extraordinary step.

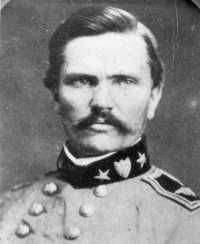

He asked the regular soldiers in his command if they knew any of the people over there, the ones they were fighting, the ones who would be killing them the next day. Several knew the commander of a division in William J. Hardee’s corps. He was all soldier, they said, West Point Class of 1844, who had left the army in the 1850s. When the war broke out, he had refused to resume his service in it, choosing instead to fight for the South. Despite that, people who knew him insisted the man was incapable of deceit or dishonor. Wilder decided to ask this man a question.

An exchange of notes made arrangements for General Simon Bolivar Buckner of the Confederate army to receive Colonel John T. Wilder under a flag of truce after midnight. After a stiff but cordial exchange of ordinary pleasantries, Wilder candidly admitted his inexperience to Buckner, but the admission has been misinterpreted. Wilder wasn’t talking about being callow in command, and to represent it as such maligns a capable soldier and unfairly makes him out to be a dullard. Wilder knew that fighting overwhelming odds meant inevitable defeat and likely annihilation, but he didn’t know if he could avoid that fate with honor. He wanted Buckner to tell him what a West Point man, Class of ’44, would do.

“Well, Colonel,” Buckner said, “I can’t advise you about that. You are in command of your troops, and you must decide for yourself what you ought to do.”

This was no help at all, and Wilder sat in silence. He looked more forlorn than when he arrived. Buckner suggested they take a walk. They strolled along the Confederate positions, and Buckner carefully pointed out the artillery placements. Wilder saw numerous cannons trained on Munfordville. Buckner told him that they would open fire at dawn. “It is for you to judge,” said Buckner, “how long your command would live under that fire.” His tone was matter-of-fact rather than menacing. Wilder began counting the guns. When he reached the mid-40s, he stopped. “I believe I will surrender,” he said.

The terms were generous: Wilder’s men were paroled on their honor not to take up arms again until notified that they had been exchanged for a comparable number of Confederate prisoners. They were then free to go. It was early enough in the war for that sort of thing to happen.

John T. Wilder was forever grateful for his treatment at the hands of Simon Bolivar Buckner. There had been no condescension, nor had Buckner’s manner been embarrassingly sympathetic. They had spoken as two reasonable men dealing with a disagreeable situation, and Buckner had been careful not to advise Wilder to surrender. In fact, at one point, he had told Wilder that it was his duty to fight to his last man if he thought it would benefit Buell’s army somewhere else. Wilder thought for a moment but decided there was no advantage to be gained for anyone by the slaughter of his command.

They did not part as friends, but for the space of an hour, they had not been enemies. The professional soldier in Buckner was relieved that fellow soldier John Wilder would not needlessly die at Munfordville. But another reason made Buckner grateful for the silent September dawn that followed their meeting. Confederate artillery would have started the destruction of the little town, and the ensuing fight would have completed its obliteration. Munfordville was Simon Buckner’s hometown.