The old man’s hand trembled as he put pen to paper. Palsy had afflicted him before he reached middle age, and he was used to working around it, but nervousness always worsened it. He managed to scratch out “Quincy January 1st 1812” and then paused to gain control of the shivering pen for the next line: “DEAR SIR.”

He paused again. Perhaps a little joke would help break the ice. “As you are a Friend of American Manufactures under proper restrictions,” he began, a playful way to announce that he was sending a package “containing two Pieces of Homespun” for the recipient’s inspection.

The letter was brief and, at most, an exploratory opening. It ended with a short paragraph with family news. He concluded with wishes for a happy New Year. The old man put down the pen and shakily folded the sheet into a rectangle to seal with wax. He scrawled the address:

Thomas Jefferson

Monticello Virginia

When John Adams’s letter arrived in Virginia some three weeks later, it didn’t come as a surprise. A mutual friend had told Jefferson that Adams was planning to write, and Jefferson might have thought the letter was a bit overdue. Some people reckoned it was twelve years overdue. The two were hopelessly estranged. At least one friend thought it was time to do something about it. Adams had steadied his hand to try.

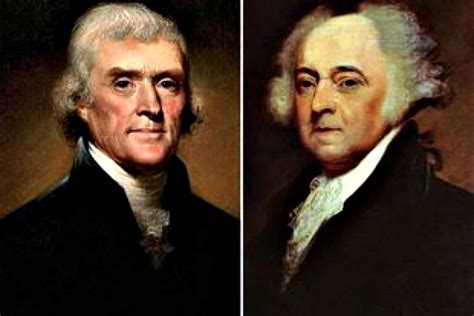

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams had once been friends, which made the rift between them all the more bitter. In fact, it was seemingly irreparable. Almost forty years earlier, they met as members of the First Continental Congress, Tom a young 32 and Adams an old 40. In 1775, the colonies were beginning to organize a vaguely united protest against British imperial policy, but there was never anything vague about the voice of John Adams. To his delight, the peppery man from Massachusetts discovered that there was nothing vague about the pen of Tom Jefferson. It was seemingly foreordained then that the following year they would lead the way for American independence. On the committee appointed to make a case for breaking with Britain, Adams was the sounding board for Jefferson as he labored over the paper that would become the most famous document in American history.

When the Continental Congress began editing Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence, he squirmed, but Adams stood to fight for Tom’s every word. Congress made changes anyway, in part because almost everybody found Adams pompous and tedious. Jefferson, too bashful to speak, watched in wonder as the little round man bellowed in protest over every alteration, his trembling hand clenched behind his back and the other jabbing at the air to punctuate his clipped Yankee accent. Watching him that way, Tom thought John Adams was mighty fine. He would later tell James Madison that anyone who took the trouble to know Adams would love him.

Abigail Adams, who certainly loved her husband, certainly agreed. Thomas Jefferson’s friendship for her mostly friendless husband endeared the tall, shy Virginian to her. They all found themselves in Europe after the Revolutionary War when Adams and Jefferson represented their new country to Britain and France. They talked of being “neighbors” and acted like family because Abigail realized Tom was bashful rather than aloof. She also knew that her seemingly pompous and tedious husband was actually affable and outgoing, genuinely funny, and often tried to find humor in everything, even himself.

With a clear eye about the strengths and weaknesses of her husband and his friend, she let an easy friendship mature in its own time and was soothing rather than cloying in helping Jefferson mend from his wife’s death, which had nearly killed him. In time, his smile reminded her of sunshine. He liked the way she laughed and even more how she thought and spoke her mind. She was kind to his daughters as if she were their mother, and her judgment about their father was characteristically blunt: Tom Jefferson, she said, was “one of the choice ones on earth.”

They basked in one another’s company abroad. However, stark philosophical differences between Abigail’s “dearest friend” and “the choice one on earth” were waiting to divide them politically and smash their affection. It began slowly when they returned to the United States to serve in the new constitutional government. The insignificance of the vice presidency chafed the already prickly Adams, and arguments with Alexander Hamilton turned the ordinarily cheerful Jefferson into a brooding alarmist. Amid the venomous and shifting tides of politics, Jefferson’s anxiety that the government was becoming too powerful clashed with Adams’s belief that it wasn’t powerful enough. At first, they wanted to believe that they misunderstood each other, but in the end, they were convinced they understood each other perfectly. Neither realized that the failed presidency of John Adams had left him cynical and sour and that Jefferson’s presidential victory in 1801 had completed his evolution from a dispassionate philosopher into an artful political partisan.

And so, a quarter-century after the two had turned politics into poetry with the soaring declaration of 1776, they managed to turn personal relations into poison. The breach was so complete that Abigail would not tolerate the sound of Jefferson’s name, and her husband dismissed Jefferson’s talents as superficial and sordid. For his part, Jefferson thought Adams had become a treacherous acquaintance when unmasked as a monarchist.

The animosity ran so deep that it thwarted even the most promising chances for reconciliation. In 1804, when Jefferson’s younger daughter Polly died, the news took Abigail’s breath away. She wrote a letter of condolence to the father of the little girl she had tickled and cosseted in London so many years before. Jefferson ruined the gesture with a needlessly sharp note that caused Abigail to end the correspondence.

Five years later, Benjamin Rush tried to cajole both Adams and Jefferson to renew their acquaintance, if not their friendship. Jefferson told Rush it was useless dealing with those people. Adams answered Rush with a sarcastic letter that denounced Jefferson as a hypocrite.

Benjamin Rush persisted, though, and time wore away the anger. If Adams wrote, would Jefferson read? Rush asked the man now retired at Monticello. Perhaps, said the Virginian. Armed with that thin encouragement, John Adams began the new year of 1812 by offering to send Thomas Jefferson “two Pieces of Homespun lately produced in this quarter.”

At the end of January, Jefferson did more than open the letter. He tore off its seal and devoured its contents. And he read so quickly and rushed to reply so briskly that he clearly misunderstood John Adams’s little joke. Eager to seize the opening about “homespun,” Jefferson wrote a discourse on domestic manufacturing in Virginia. He was clearly clearing his throat, though, and the balance of his letter was nostalgic in tone and filled with pleasant reminiscences.

Then Adams’s package arrived containing the “homespun.” It was a 2-volume book that his son John Quincy Adams had written while on the faculty at Harvard. Jefferson had to smile. Just as Abigail had hugged his Polly in London, he had counseled the teenaged Johnny (as John Quincy Adams was called) in the way of a kindly uncle. Jefferson immediately wrote another letter to Adams, sheepishly admitting his mistake and complimenting the boy he had known in happier times.

In a way, it was the best way of all to start happier times again, and once started, there was no stopping them. Beginning in 1812 and for the next fourteen years, Adams wrote Jefferson quite often, sometimes putting letters in the post several days in a row as new ideas occurred to him. Jefferson wrote lengthily in response, but his frequency couldn’t match that of Adams. He was humbled that he wrote only 39 letters to the 109 Adams deluged him with. Adams understood because he had never forgotten the habits of the shambling Virginian who was busy with his farms, busy remodeling his house, busy tinkering in his workshop, busy founding a university, and busy answering scores of letters from other correspondents, many of them strangers. In 1820, Jefferson counted more than a thousand letters arriving at Monticello, an average of 25 a week. He answered them all, often at length, a chore that had him writing letters from dawn to early afternoon and again for a couple of hours in the evening, every day of every week. “Never mind it, my dear sir,” Adams assured him, “if I write four letters to your one; your one is worth more than my four.”

Which wasn’t true, but was kind, even though Adams, even in this last phase of their lives, could be peppery. When Adams could not help himself, Jefferson routinely refused to take the bait and deflected efforts that would have easily picked a fight in an earlier time. It reflected their consistently different personalities accentuated by old age but made strangely complementary by the wisdom of their many years. Adams remained pessimistic to the end of his life, believing that “people and nations are forged in the fires of adversity.” Jefferson would not have disagreed with that, but he strongly departed from Adams’s belief that most people would choose wrongly when given the chance to do good or ill. When the reaction to Napoleon’s antics returned much of Europe to a disturbing level of autocracy, Adams felt vindicated in his view that people were always inclined to suppression and submission. Jefferson, however, spoke of July 4, 1776, as a kindled flame that had “spread over too much of the globe to be extinguished by the feeble engines of despotism.”

Adams might have shaken his head over the eternal optimist, the man he took to calling “the sage of Monticello.” Jefferson, in turn, hailed Adams as a fellow “Argonaut” in the voyage to liberty. He spoke of their renewed friendship as “sweetening to the evening of our lives.” Adams must have smiled over the strange effusiveness of his reserved friend.

Though nostalgia tinted every letter and retrospection informed their remarks about the great events they had seen and had often shaped, especially the American Revolution, they did not live in the past, or even in the moment. The sage and the argonaut used the past as a vantage from which to chart the future while discussing planting peas, patching fences, and the toll of age. Adams’s palsy made it almost impossible for him to write legibly, and for him, the pen became “as terrible as a sword to a coward.” Jefferson’s right wrist that he had broken in Paris thirty-five years earlier grew stiff and more painful each year, and his enlarged prostate had him resorting to a self-administered catheter. When he slipped on a terrace at Monticello and broke his left arm, the maneuver was more difficult.

Yet, they both rode their favorite horses, and when Adams could no longer swing into a saddle, he walked the hills around Quincy. Jefferson freely admitted that “the hand of age” was heavily on him, and finally, the two talked of mending souls, for eventually, they got around to discussing God. Both believed.

In February 1825, Adams was in a winsome frame of mind: “We shall meet again,” he wrote to Jefferson, “so wishes and so believes your friend.” But both knew it unlikely as the hand of age weighed on them both more resolutely. The following spring, Jefferson’s favorite grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph (always called Jeff) traveled to Boston and carried a letter from his grandfather to Adams. Delivering it was an excuse for Jeff to meet, Jefferson explained in the note, “a hero” of the founding. Adams was flattered by the gesture, charmed by the visit, and delighted by Jefferson’s letter. “My health is but indifferent,” Jefferson had written, “but not so my friendship and respect for you.” Adams wrote back immediately: “Your letter is one of the most beautiful and delightful I have ever received.”

The two had no reason to think that these would be their last words to each other, but the weeks leading into the summer of 1826 saw them faltering. Neighbors in Quincy invited Adams to attend Fourth of July celebrations as an especially honored guest since it was the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Growing more feeble as the day approached, he stayed in, and by the Fourth, he was slipping in and out of consciousness. He slept through the day’s hot and humid morning hours, but in the early afternoon, his eyes opened, and he spoke. Those around the bed would remember the exact words differently, but they never differed on what they meant: “Jefferson lives!” By 6:00 that evening, John Adams was dead.

And by all appearances, he had been wrong. Jefferson also had fallen gravely ill on July 3 and was fitful in his bed, repeatedly mumbling the question “Is it the Fourth yet?” until one of his relatives lied and said it was. Jeff Randolph was there, anxiously watching the clock, and when it passed midnight and then came the dawn, he was relieved that his grandfather had made the 50th anniversary. Possibly Jefferson realized this, but probably not, for he never spoke again. When John Adams in Quincy proclaimed Thomas Jefferson alive, the Sage of Monticello was already dead. Jeff had marked the time of his grandfather’s passing as almost precisely fifty years to the hour that the Declaration of Independence had been presented to the Continental Congress.

“We shall meet again,” John Adams had promised Thomas Jefferson, and in the end, they did not keep each other waiting. And just as Jefferson had been mistaken about Adams’s “homespun” jest years earlier, we might all be mistaken about the real meaning of Adams’s proclamation on the day of America’s jubilee. Perhaps he was talking about something else. Adams knew that as long as there is liberty, sages and argonauts cannot die.