In August 1780, Benedict Arnold became the post commander at West Point for reasons nobody could quite understand, even the man who recommended the appointment. Though strategically crucial in itself, West Point was a remote and tranquil place that seemed ill-suited to someone accustomed to impetuous exploits and dangerous deeds. Arnold’s reasons would be revealed soon enough.

George Washington first met him at army headquarters outside Boston in 1775. Arnold was then thirty-four, short and stocky but striking. He had an audacious proposal, and Washington was receptive to it. Arnold wanted to lead a small force through the Maine wilderness to cooperate with the American campaign against Quebec that was already underway. The Maine country, then part of Massachusetts, was a mysterious place never adequately mapped and likely to have unimagined obstacles, but Arnold was confident.

His first conversation with Washington set a pattern. Arnold was in Boston because Congress had passed him over for the command of the Canadian invasion, despite its having been Arnold’s idea. A tincture of self-interest colored Arnold’s desire to advance the American cause in this instance, and looking back, many would see more than tinctures of self-interest in everything Benedict Arnold did. However, Washington believed that Arnold could help the campaign against Canada, partly because Arnold had visited Quebec before the war but mainly because the man was persuasive.

Benedict Arnold was descended from a founder of Rhode Island, an early governor of the colony, but his family fell on hard times during Benedict’s childhood. His father drank excessively even when things were going well, but the death of four of his six children caused him to crawl into a bottle. Plummeting family fortunes required Benedict to work as an apprentice in his cousins’ apothecary, where he learned the medicine-mixing trade, but he always thought it beneath him. Worse was to come. His father began passing out in public and landing in jail for disorderly conduct. His mother, whom Benedict adored, died in 1759, possibly because she couldn’t stand life any longer, and his father finally took his last drink two years later. Benedict and Hannah, his only surviving sister, mourned their mother. As for his father, it was good riddance to bad rubbish as far as Benedict Arnold was concerned.

Arnold’s cousins staked him to his own establishment, and as soon as he could, he moved to New Haven to escape the family’s disgrace. There he worked as if goaded and spurred, something he would do for the rest of his life. His drugstore and bookshop blossomed into a merchant house. Arnold became a seafaring captain aboard the establishment’s ships, working the rich Caribbean and Canadian traffic, having adventures, and making a name for himself as a shrewd bargainer and bad enemy. Wealth won him a wife from a prominent family, the twenty-two-year-old daughter of New Haven’s high sheriff, and they seemed happy as three boys came in quick succession. But Arnold’s constant travel and rumors about him and low women in the West Indies clouded the marriage.

The outbreak of war with Britain fed Arnold’s love of action and adventure. He responded to Lexington and Concord by helping to capture lightly defended Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. The exploit won him applause and recognition, but it also revealed a fundamental flaw in Benedict Arnold. He saw praise of others as detracting from his own. In these instances, he could be thin-skinned, and a quarrel over command at Fort Ticonderoga caused him to resign his commission.

It was then that he proposed invading Canada, and as it turned out, it was a terrible idea. Arnold reached the outskirts of Quebec, but only after a trek so arduous that it cost him more than half his men, with the rest reduced to eating their dogs and then chewing shoe leather to stay alive. The American siege that followed ended during a blizzard, when a disastrous American attack left Arnold wounded. Nevertheless, Arnold’s audacity against long odds inspired admiration and acclaim. As the ill-fated Canadian campaign concluded with a general American retreat, he managed to extricate the army and even mount a defense of Lake Champlain in October 1776. Though the defense ultimately failed, many correctly judged Arnold’s exploits to have delayed British operations in the region for months. He seemed an American hero when they were scarce on the ground, and he won promotion to brigadier general. Congress, however, placed other officers in command of the army Arnold had saved.

Such treatment could provoke resentment, and Arnold’s anger over it seemed justified. Yet, there was something troubling in his character. Here was a potentially great man who committed petty and sometimes pointless misdeeds. He engaged in small grafts for puny profits, behavior that made him enemies and jarred his admirers. Anyone who had to work with him almost always regretted the association, for Benedict Arnold was a bundle of contradictions. Americans would later portray him as a coward and invent stories about his youth in which he killed baby birds and spread broken glass on paths to cut the bare feet of schoolmates. But he was much more complex than an operatic villain. He was courageous when the challenge was most daunting, and his exploits made him easy to admire. It was his ugly temper, constant complaints, and little corruptions that made him hard to like.

His private life was untidy and suggested deep flaws. His wife died in 1775, and he wasted no time looking for a replacement. He found just the girl in a pretty Bostonian named Elizabeth Deblois, but she wasn’t much interested at first, and Arnold’s clumsy courtship with inappropriately expensive gifts put her off completely. The otherwise unremarkable event of an older man pursuing a fresh-faced girl revealed Arnold at a core level. It did not trouble him that Betsy Deblois, like her family, was unshakably loyal to the king and opposed the cause Arnold was serving. Plenty of families had divided on this question, but they existed as families before it became an issue. Betsy’s loyalty to a cause entirely at odds with his was of little consequence to him. He was willing to marry an enemy.

When Congress passed Arnold over for major general in early 1777, Washington could barely talk him out of resigning. He had to appeal to Arnold’s vanity as much as his loyalty. Arnold finally received his promotion, but he immediately complained that he was junior to people unfairly promoted before him, continuing his turbulent relations with brother officers. Still, his battlefield exploits were impressive, and his courage hid his crippling insecurities. Both worked to stifle accusations that he was a chronic grifter.

Sent back to New York to help oppose John Burgoyne’s invasion in 1777, Arnold exhibited his personality’s good and bad sides. He argued with his commanding officer beyond the point of insubordination and was relieved of command. He ignored that order and led the decisive charge that sealed Burgoyne’s fate at Saratoga, an American victory that forever crippled the British war effort. It also forever crippled Benedict Arnold: he again suffered a severe wound, and the surgeon ineptly set his shattered left leg to make it a couple of inches shorter than the other. He had a halting limp for the rest of his life.

Washington thought the military governor’s post at Philadelphia would be a peaceful assignment for a semi-invalid. He appointed Arnold to it, but it was a grave mistake. Arnold plotted petty grafts and lavished money he didn’t have on women he should have avoided. A court-martial reprimanded him in 1779, but Washington took pains to soften the reproach. Arnold repaid that kindness by making secret investments with British firms and then using his authority to boost their profits. He lived ostentatiously, socialized with Loyalists, and married the daughter of a Tory family with connections to British headquarters in New York City. His bride was Margaret Shippen, half his age as her diminutive nickname “Peggy” suggested, and for many years pitied as another of Benedict Arnold’s victims. Yet rather than he being a predator and she his prey, they found each other. Peggy was complicit in everything he planned. They married on April 8, 1779, with Arnold barely able to stand at the altar because of his bad leg. As they said their vows, the happy couple was already well into a scheme to betray George Washington and smash the American Revolution.

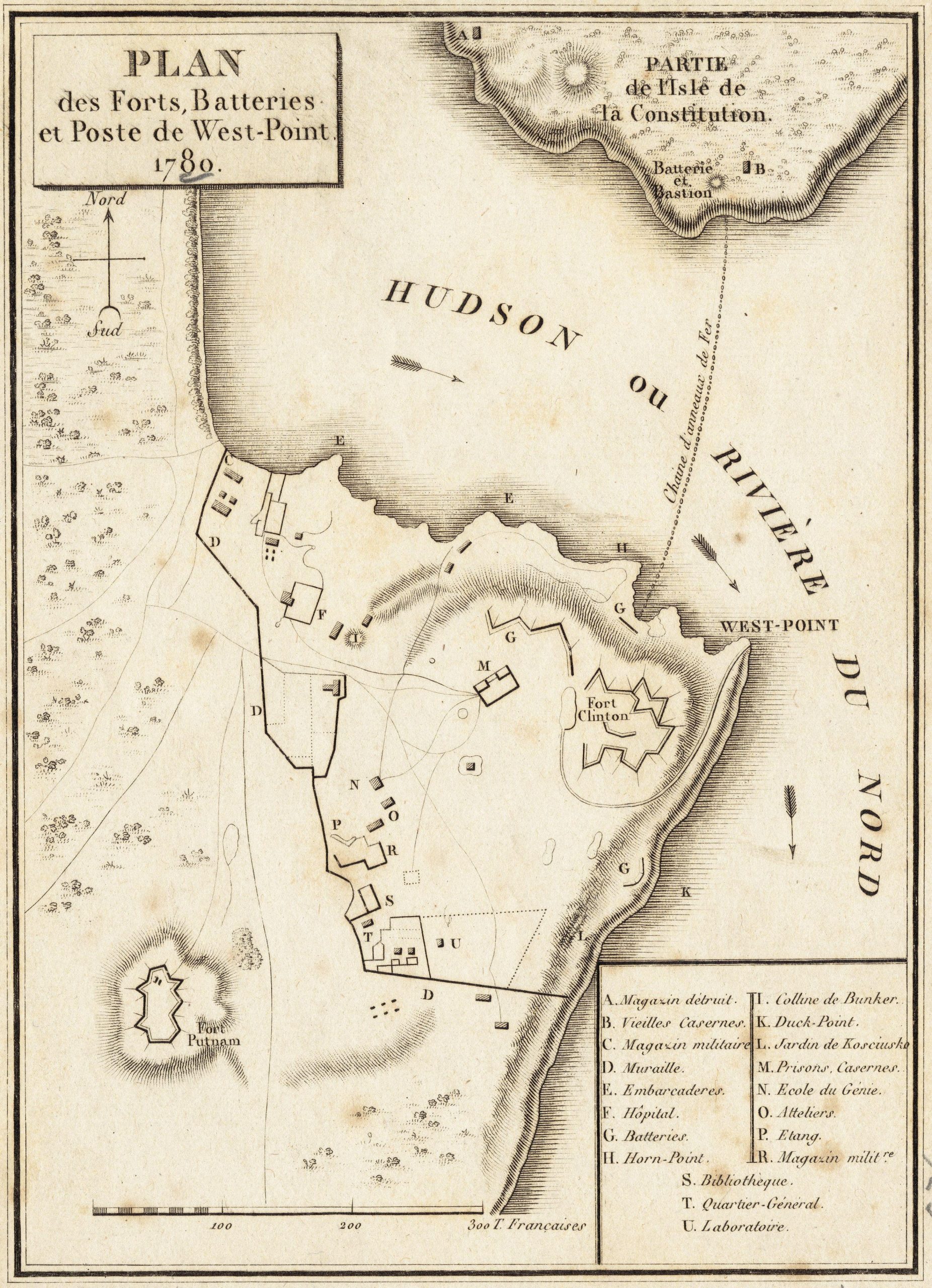

Arnold had been negotiating with British commander Sir Henry Clinton, and he continued those secret talks into 1780. He showed his “good faith” to the British with small betrayals of Americans that could never be traced back to him. When it turned up, the prospect of commanding at West Point offered a breathtaking opportunity. The place was the key to the entire region because the Hudson River’s sharp turn below brought British ships trying to negotiate it under devastating fire. If Clinton had West Point, the Royal Navy would control the Hudson, and he could isolate New England, open up interior lines of supply, and divide the American rebellion to conquer it.

For that reason, Arnold actively sought the post’s command, which bewildered George Washington. But Arnold invoked his pathetic leg, and Washington relented. Arnold received the appointment on August 3, 1780. He intended to turn over the Hudson River citadel to the British at his earliest opportunity.

Once in place, he wasted no time putting everything in motion. He stripped West Point of defenses and scattered its garrison on pointless errands to make its surrender an accomplished fact. Everything he had planned very nearly happened just as he wanted. But his British contact was arrested, and an unexpected inspection visit by Washington and his staff threw all into disarray. Arnold escaped just hours before Washington arrived, leaving Peggy and their infant son behind. While Washington and his aides sorted out the particulars of the treason that day, Peggy Arnold feigned madness so convincingly that Washington sent her home to her family. Peggy escaped by guile, her husband by flight.

Among Americans who fought for independence, Benedict Arnold profited the most, and that was by trying to sell it out. He was unfathomable to Americans, and none more so than his fellow officers. Nathanael Greene muttered that “never since the fall of Lucifer has a fall equaled this.” But Arnold had not so much fallen as he had settled, like flowing water, to his natural level. Everything for him was expendable, including people, not just at the end but from the start. When the pursuit of Betsy Deblois did not work out, he did not even pause before moving on. He had made copies of his love letters to her, using them to court Margaret Shippen.

Whether it was Betsy Deblois or Peggy Shippen or George Washington, Benedict Arnold saw everyone as an opportunity to be used or cast off as convenience dictated. Recycled love letters were as meaningful as recycled causes, especially for a calculating man who counted time as money. Moreover, he was a great and courageous soldier, which made him a peerless hero in the crucial hours of the American Revolutionary War. But at his core, he was a despicable combination of opportunism and avarice. Those would have been footling flaws in a lesser man, but Arnold raised them to grotesque perfection. That was what made him a peerless traitor.