Ironies for Napoleon Bonaparte began to multiply in the second half of 1815. In the first part of the year, he had fled Elba to reassert his authority in France, raise yet another army, and mount yet another military campaign. The measure of that time was to become famous as “The Hundred Days.” Less well known is that almost another 100 days of a very different sort were to pass from the moment he fled France to the moment he landed at the place of his final exile, the “dreadful place” called St. Helena.

With good reason, Napoleon Bonaparte grew weary of the voyage on HMS Northumberland. It lasted more than two months, and as the Northumberland pounded south farther and farther from Europe, the trip for Napoleon and his companions became dispiriting. They had all thought they would be settled pleasantly in England, and when they were told otherwise, Bonaparte had gone ashen. One woman in his entourage had to be restrained as she tried to throw herself off the ship.

He had not thought it would be this way, even as he ran from the Prussians who would have killed him or the French who would have jailed him. He knew that only the British would spare his life, and for the time being, that was all that mattered. He rushed to their protection with dreams of living somewhere in the English countryside.

Yet, by the autumn of 1815, any residence anywhere near Europe was out of the question for Napoleon. Not just Europe but the world demanded that the British avoid the errors of Elba. That mild Mediterranean banishment had been too close, encouraging intrigues and plots, and finally, Bonaparte had escaped it to resume his imperial title and reassert his imperial presumptions. After the bloodbath at Waterloo, the British had learned their lesson: Napoleon Bonaparte, said the First Lord of Admiralty, would never again disturb the peace of Europe and renew “the calamities of war.”

Napoleon did not know this was settled British policy when he came to them in his customary costume, the uniform of the Chasseurs of the Guard: a green coat with scarlet cuffs, his breast adorned with the Legion of Honor’s star, a cross, and an iron medal in the shape of a crown. He wore a white waistcoat with white breeches and long boots, all topped by the cocked hat he had made into his emblem. His companions were still calling him the emperor.

True enough, proper dress, faultless decorum, and an empty title were small matters in the balance of life and death, but as his world and wield shrunk, such things became greatly important to him. He was being rowed to the British man of war when he suddenly conceded a weakness. Napoleon was color blind. He nervously pointed to his coat and asked a lady of his party, “Is it blue or green?” For the first time, she noticed how fat he had become; worse for both of them, she noticed how small he had always been.

He quickly regained his composure once safely aboard a British ship. Feeling safe again, he became cocksure and was occasionally but deliberately rude. It was the way he had always gotten his way. Nevertheless, his hosts were cordial and respectful, and British sailors suppressed their curiosity, thoughtfully averting their eyes during his evening walks on deck. Officers dined with him and his companions. The French sipped their wine in silence and pretended not to notice the snuffling and slurping little man they called their emperor as he gulped and gobbled everything but vegetables. The British officers traded uncomfortable glances as Napoleon never touched a knife or fork but ate with his hands.

The news that they were to sail for St. Helena was a setback for him. Being placed in such a remote location more than complicated his chances of escape. Although Bonaparte seemed beaten down by recent misfortunes, he was hardly permanently beaten in his own mind. Still, as the Northumberland approached St. Helena 200 years ago this month, his prospects appeared bleak, and therein lay another irony. Though it was autumn in Europe, St. Helena’s southern latitude reversed the seasons, just like life had reversed Bonaparte’s fortunes. It was fall for the fallen emperor, but October signaled the onset of the island’s spring.

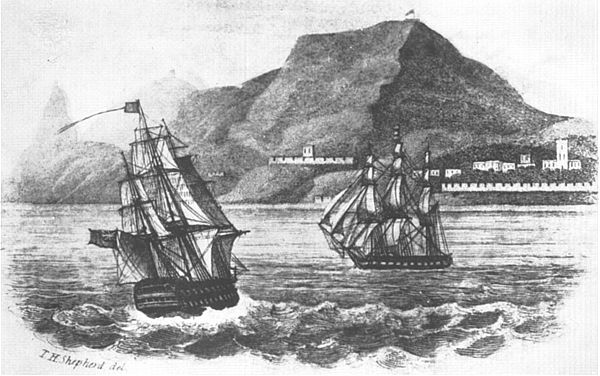

On October 15, 1815, the Northumberland dropped anchor off Jamestown, and Napoleon had the unsettling feeling that he was looking at the last place on earth. A thousand miles from Africa and more than two thousand miles from Brazil, it was an enormous rock, seemingly barren, with a sheer face towering above the water. Cliffs from 600 to 1200 feet high suggested an impregnable fortress.

In that regard, the British had improved upon nature. The heights above the coast bristled with powerful batteries. No ship foolish enough to venture within their range could have withstood them, and they would have been ready for any vessel’s arrival. Elaborate signaling systems could instantly alert the entire island about anything on the sea within 60 miles of St. Helena. The large garrison of nearly 8,000 soldiers guarding the few access points on the northern and southern coasts would have a leisurely day or two to deploy against an invasion.

Rumors told of interventionist expeditions from the day of Napoleon’s arrival. Purported plots in America and Europe to rescue and return him to France kept the British on edge even though any attempt to free Napoleon seemed most unlikely. It would have required a powerful squadron able to fight through patrolling British warships, overmatch the intimidating artillery installations, and land thousands of soldiers prepared to challenge veterans hardened by 20 years of fighting the man they were now watching over.

Yet in the shadow of the Elba disaster, the British took no chances, and their measures after a while seemed excessive. That and St. Helena’s forbidding appearance gave rise to stories about Napoleon’s cruel and unjust treatment there. These tales were published in the British press while Napoleon lived, and helped by Bonaparte’s own special pleading in letters and memoirs, they have been regrettably accepted as accurate. Yet all stories of cruelty are groundless. The place was hardly a jail, and the British running it went out of their way to ensure it never looked like one.

St. Helena appears stark and forbidding from the sea, but its interior has green fields, forested hills, and lush valleys. It was remote and insignificant, but as a place convenient for ships on the way to somewhere else, it had value for commercial powers with interests in the Indies: it passed from the Portuguese to the Dutch and then to the British, whose East India Company used it as a waypoint and an experimental agricultural station.

Its only village — Jamestown, named for the Duke of York — remained unshakably quaint. The island with its temperate climate, refreshing breezes, and spectacular views became a sort of South Atlantic Brigadoon that seemed to appear only when ships came and vanished when they left, leaving its pretty and tranquil inhabitants in the form of ageless and carefree shadows.

Such was certainly whimsy, but, unfortunately, the focus has always been on what St. Helena did to Napoleon Bonaparte rather than what his presence did to the people who lived there. After October 1815, they were hardly tranquil and fairly full of woe. British policies to guard waters made life difficult for fishermen, restrictions on ships coming to St. Helena made the most basic goods scarce, and Napoleon’s arrival and the multitude of soldiers to guard him made everything expensive.

Only Napoleon and his traveling court avoided want under these conditions, for the British made sure his larder was well stocked. And even though they had allowed Bonaparte to squirrel away considerable sums in safe British banks, they generously paid for part of his expenses. The gesture freed up his money to bribe guards at hand and fund intrigues in faraway places.

Despite his reputation for fearlessness, Napoleon was scared of dying, especially at an assassin’s hand. It caused him to have heavy locks installed on his bedroom doors and to instruct valets to stand nightly vigils as bodyguards. He routinely thought his coffee tasted peculiar or a wine’s bitterness betrayed its poison, and his first night ashore at Jamestown so unnerved him that he insisted on a secluded residence while his permanent one was renovated. That was how he came to live briefly in a small pavilion at “The Briars,” the home of a British merchant whose daughter Betsy Balcombe years later wrote a highly romanticized account of his stay that became part of the legend of Napoleon’s final exile.

Betsy was a child when Napoleon arrived at St. Helena and was around him for only a few weeks. But her book depicts an innocent and idyllic relationship developing between a sprightly girl coming-of-age and the jovial, unassuming man who had recently been the Master of Europe. It is surprising how many people through the years have believed this preposterous story of Napoleon as a mischievous trickster full of fun, firing off good-natured quips, and delighting in the childish antics of Betsy and her siblings.

Actually Napoleon hated them all. He privately sneered that Betsy’s father was a corrupt storekeeper and thought her a brat. In any case, he was miserable at “The Briars” because it was his first taste of captivity on St. Helena. He loathed everything about the island as he would a prison. For Napoleon’s permanent residence, the British remodeled Longwood, the island’s lieutenant governor’s expansive former home. They were careful to conceal any iron bars meant for Bonaparte’s protection more than his imprisonment, and guards were instructed to keep their distance and even remain out of sight when possible. Even Napoleon’s maitre d’ later admitted that “it was not St Helena that was so much at fault.” Rather, “it was the being there.”

So it didn’t matter that at Longwood he could enjoy hot baths lasting for hours, eat grand meals prepared to his exact specifications, and gaze out at splendid vistas of the ever-changing sky and sea. Napoleon complained about everything and persisted in demands that his captors recognize his title as emperor. He demanded an end to all scrutiny of his movements, and he refused to ride St. Helena’s paths or walk beyond his garden while English officers were anywhere near. While he insisted his captors trust him, he schemed to sidestep rules governing his correspondence and was vicious toward unoffending soldiers sworn to protect him, denouncing them as would-be assassins.

He was no better with the forlorn people who had accompanied him into exile. All of them were there by circumstance rather than choice, having faced the likelihood of poverty or, worse, prison, had they remained in France. Napoleon was aware of their frail loyalty tinged with opportunism and necessity, and he made them pay for it by insisting on high formality and ostentatious ceremonies in silly ways. For example, nobody could speak to him unless he opened a conversation, a practice that made dinners painfully silent affairs.

He didn’t like to waste time eating, so he gobbled his food, gulped his wine, and was up from the table in less than twenty minutes expecting everyone to rise and leave as he did, though that meant another hour or two listening to him read aloud from books they had heard dozens of times. He often paused to explain the author’s intent in repetitive detail, a habit he carried over to walks in Longwood’s garden, which made for tedious exercise as Napoleon slowly strolled and expounded on the same topics day after day. Sometimes somebody would hang back to escape, and Napoleon would notice — he always noticed — and sneer, “Look! Running away . . . “

His selfishness and egocentrism foiled all attempts at diversion and ruined the simplest amusements. He cheated at cards because he could not bear to lose at anything. He was correct in his confidence that nobody would call him out for it. When he was bored, he pretended to sympathize with the men who had left wives in Paris by lamenting their fates as cuckolds, and he observed to the wives who had made the trip how much it had aged them. He was openly caustic with the one who had tried to jump ship.

He reserved his craftiest behavior for his British captors, deploying manipulative techniques that he had mastered over a lifetime. He first tried to extract concessions with pleasantries, and when that didn’t work, he became in predictable turns pouty, then indifferent, then rude, and finally enraged. In letters for immediate consumption and writings meant for posterity, he smeared his victims with false descriptions and outright lies about their behavior and lack of character. His treatment of St. Helena’s governor Sir Hudson Lowe was a textbook example of the method. Lowe’s reputation has suffered horribly for merely doing his duty while trying to be kind to his prisoner.

Sir Hudson Lowe was an impeccable soldier and a diligent administrator whom the British government chose as Napoleon’s jailer because he was the least likely man to act like one. He spoke fluent Italian and French, had commanded Corsican regiments during the Napoleonic Wars, and was accustomed to the company of kings and princes from every corner of Europe. A superior officer once commented on Lowe’s steely nerves and peerless resolve by declaring that knowing Lowe was in the field always meant everyone else got a good night’s sleep.

It was precisely that unshakable calm and unfailing consideration that drove Napoleon to violent rages, for his most provocative actions could not provoke Hudson Lowe. In their last meeting, Napoleon resorted to a spittle-flecked tantrum over a contrived complaint while Lowe stood expressionless for a quarter-hour. When Napoleon paused to catch his breath, Lowe calmly said, “Quite so.” Bonaparte didn’t know how to deal with such a man.

At least right away. As it happened, he finally dealt with Hudson Lowe in the same imposing way he had dealt with Europe for almost two decades. Much of the controversy over Napoleon’s allegedly bad treatment at St. Helena stemmed from his malice toward Lowe and people’s willingness to believe it was merited. When Bonaparte was done, Hudson Lowe was to be remembered as the one who lost his temper and violently shouted at his patient prisoner, not the man who was flawlessly polite in the face of incredible abuse.

In that respect, historians have incorrectly judged “The Hundred Days” after Elba and the events that ended at Waterloo as Napoleon Bonaparte’s last campaign. However, it was really only a prelude to the last campaign, the one he mounted at St. Helena to reclaim his reputation by reshaping his image as a prisoner, making it into that of a Byronic hero greatly wronged and sorely tried. His last army for this last campaign was irresistible, numbering in the millions, its rank and file a gullible public eager for heroes and willing to worship them. His officers were thousands of Betsy Balcombes scribbling away to recall a titanic figure, not a small, fat man who, when deprived of his whip, found wheedling worked just as well. Napoleon’s last campaign was to reverse reality, the way St Helena did the seasons, to make autumn into spring, to transform disaster into triumph.

In the most consequential of all contests, he conquered with his shadow the very nature of time, the most formidable of all man’s foes. In this, his final campaign, Napoleon won.