Lucy was a Scot. Her birthplace was on the River Clyde whose “bonnie banks” Sir Harry Lauder romanticized when he warbled about “Roamin’ In The Gloamin’.” In his song, Sir Harry is thrilled to have his lassie by his side in the gloamin’, meaning in the soft shades of twilight. However fetching she may have been, though, she could not have held a candle to Lucy. As lassies go, Lucy was a heartbreaker. She was built for speed but was an elegant girl in every way and from every perspective. Sailors who loved her lines were the ones who nicknamed her “Lucy.” Years later, when she was killed, the entire world would first be stunned by disbelief and then would seethe in anger. Sailors would never forgive the men who did it.

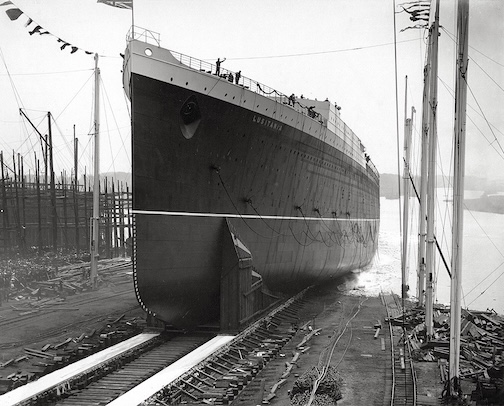

Her formal name was RMS Lusitania, so christened on June 7, 1906, by Lady Inverclyde in the traditional method of smashing a champagne bottle across her prow. A month shy of nine years later she suffered an act of violence so breathtaking that it ended an era. The First World War had begun the previous fall adorned with Old World badges of duty, honor, and gallantry. And though the trench warfare in Europe would quickly destroy such notions, what happened at 2:10 on the afternoon of May 7 instantly revealed old, cherished ideals of chivalry to be rotting relics, not just of a simpler time but of a completely different world.

Exactly 110 years ago, Lucy was off the coast of Ireland when a torpedo from a German submarine ripped open her starboard hull near her bow. A second, catastrophic explosion occurred internally, and she sank in less than 20 minutes. More than a half of her nearly two thousand passengers shared her fate. Those who escaped it endured a harrowing ordeal from which many never fully recovered emotionally and psychologically. It did not help that what many suspected at the time turned out to be true — that the British government had turned this lovely ocean liner into a gunrunner, and that the German navy had disregarded innocent passengers who, in effect, were being used as human shields.

For the ship, it was the most awful way imaginable to end a career that had been stellar at its start. If the description in the opening paragraph makes her sound like a breathtaking babe, blame the talented naval architect Leonard Peskett, who designed her for the Cunard steamship line with the sort of loving attention Pygmalion brought to sculpting Galatea. She was decked out for opulence, comfort, and speed, and the result was a luxurious miracle of elevators, electric lighting, climate control, palm trees, damask draperies, marble tiles, mahogany panels, elegant furniture, grandly appointed staterooms, ceilings formed with friezes, walls adorned by art, and spaces filled with artifacts that any museum in the world would have coveted. She had all the amenities of a small town, the industrial capacity of an enormous factory, and restaurants fine enough to compete in any cosmopolitan city. Her cabins were spacious in all classes, exceeding her nearest rivals’ square footage by giving every passenger nearly half again as much.

Lucy’s complex and varied interior was a seamless mixture of brute mechanical energy and soft loveliness. Similarly, her exterior melded grace, enormity, and power. She rode in the water like a swan, but she was meant to cover vast ocean distances like a sprinter, and that combination of beauty and purpose was so effortlessly attained that she could seem supernatural. The future novelist George Blake was a boy when he saw her passing down the Clyde. Lucy was not more than hours old and headed for the open sea. He couldn’t take his eyes off of her. He had never seen anything so wonderful, so perfect.

For all her beauty, Lusitania did not feature many design innovations. With her keel laid almost two years to the day prior to her launch, she had been altered and modified as circumstances required, but those changes were more on the order of variations in established forms. Her blueprints were drawn roughly at the same time as the other two members of Cunard’s grand trio, Mauretania and Aquitania, and none of these ships featured a radical break from customary naval designs. Yet their variations reached a pinnacle by achieving iconic elegance. The result would fasten in the 20th century mind the concept of how an ocean liner should look.

At the time, Lusitania was most famous for changing everybody’s expectations of how an ocean liner should behave. Her real departure from established forms was technological. She was the first completely electrical ship with incandescent light bulbs, a wireless telegraph, and air conditioning. As amazing as that gadgetry was, her truly striking features were cutting-edge applications of electricity for her steering mechanisms, for closing watertight bulkheads, and for fire detection. Most impressive, though, was how she harnessed and implemented steam power in radically new ways. She boasted 25 boilers generating steam to rotate 4 Parson’s turbines. Those massive devices had a total of 3 million individual blades and could sustain an average motive force of 70,000 horsepower. The turbines were directly connected to 4 triple-bladed props, perfectly trimmed and set in balance to have some rotate clockwise and others counter-clockwise and thereby achieve the most effective propulsion. Preparing this powerful lady for her maiden voyage from Liverpool became a spectacle in itself, for Lucy had a big appetite for coal. No fewer than 22 trains were required to freight the more than 6,500 tons of the stuff to fill her enormous bunkers. Her Scotch boilers powered her steam turbines, and afterwards high-volume pumps condensed the steam with cold seawater piped in at the rate of 65,000 gallons per minute.

All of this meant that she was quite fast. In fact, she was jaw-droppingly fast. At the time she was the fastest manmade thing on the ocean, able to glide along at 25 knots (almost 30 mph) without breaking a sweat and on occasion even push 29 knots when feeling frisky. Passengers on liners touted as “speedy” would see a shadow appear on the aft horizon and over the course of the day watch it take form as a ship. They would see it overtake and glide past their ship and then gradually vanish over the forward horizon. They would be awed, but the crew on the bridge would grumble that it was “only Lucy, showing off.”

Indeed. But among British crews the grumbling was husky with admiration. Lucy was the first vessel in the history of ocean navigation to make the Atlantic passage in four days. She earned the “Blue Riband” in the first four years of her westbound voyages, the informal honor given to the liner with the fastest average crossing speeds. But it was only fitting that she should do this because speed was the principal reason she was created. German ocean liners had pioneered the concept of the floating palace to sweep passengers across the Atlantic in the midst of period decor. German primacy during the first years of the 20th century embarrassed Britons accustomed to dominion in all things nautical. German preeminence in both style and speed also gave their liners a competitive commercial edge at a time when roughly 50,000 seagoing passengers were on the Atlantic Ocean each week of every year. Cunard’s bold answer was to build not only the biggest and most opulent ship but the most nimble. Wary of doing anything by halves, Cunard built three. The Lusitania was the first launched.

With four enormous funnels, she was 878 feet long, had a beam of 87 feet, and measured 60 feet from her boat deck to waterline. Those statistics made her for a time the largest ocean liner in existence. But as you might have noticed, “for a time” and “at the time” are phrases that sadly define the life of Lusitania. Her two younger sisters themselves became her first rivals, and the one coming soon after her, Mauretania, was a bit larger at launch, immediately overtaking Lucy on that score. And like a kid sister whose eyes are set just a bit differently — for example, Mauretania’s deck vents were curved rather than flat like Lusitania’s — the differences caused some people to think the Mauretania a bit prettier. And after a few years of adjustments, Mauretania was a bit faster. And by then, she was a bit more famous and a bit more loved. Nobody was able to explain why this happened, but it did. Supplanted by her sister, Lucy was then overshadowed by the larger class of fast luxury ships, such as Titanic, whose tragic maiden voyage secured for her an especially romantic place in maritime history. Put bluntly, the rapid pace of architectural development and technological advancement made Lusitania just another ship in rather short order. If not for what happened to her that May afternoon in 1915, she would be no more memorable than scores of other ships that had plied the Atlantic passenger trade.

But in the summer of 1907 just before her maiden voyage, she was bright, shiny, and pretty. And very, very fast. As she sliced through the water almost soundlessly, George Blake couldn’t take his eyes off of her. Blake would later write novels and a chronicle of the River Clyde, books filled with gritty realism. But when he first saw Lucy, he was 12 years old and in a tender frame of mind. He was thunderstruck by her. He felt his throat tightening and his eyes welling. She was all beauty and perfection. Her wake gently lapped the bonnie banks of Clyde as she made way in the gloamin’, a lovely lassie, showing off.