For many Americans in the 1820s, Washington DC had become as alien as the mountains of the moon. It was a predictable situation. Concerns about establishing a federal district solely to host the capital were older than the government itself. During the debates over drafting and ratifying the Constitution, Virginia skeptic George Mason had predicted that such a locus of power would “become the sanctuary of the blackest crimes.”

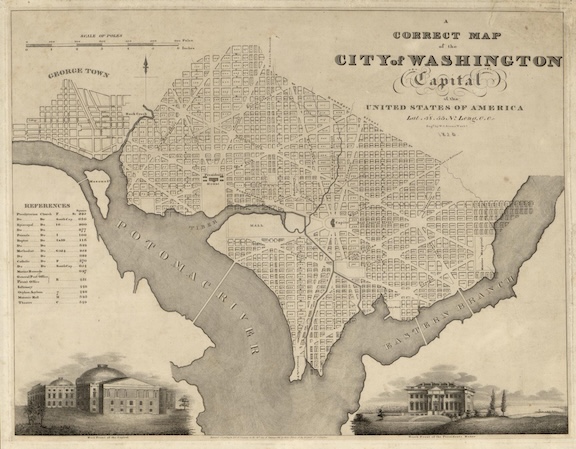

Foreigners found the place baffling, a village “only kept alive by Congress.” And for every admiring description—a Portuguese minister marveled over “the city of magnificent distances”—there was an unflattering one about wallowing pigs, wandering dogs, and distances more peculiar than impressive. “The houses are here, there, and no where,” said a British actress, who noticed how the streets were only “roads, crooked or straight, where buildings are intended to be.” There was a considerable amount of open space so that “in the midst of town, you can’t help fancying you are in the country.”

Ordinary Americans, however, had begun to doubt that a rustic setting promoted healthy government. Washington’s problem wasn’t being half-finished. It was the “congregation of government offices . . . where political characters, secretaries, clerks, placeholders, and place-seekers . . . congregate.” Men on the make jostled at the public trough, some to dispense favors, others to receive them, in a dizzying whirl of intrigue and disregard for the public trust. For every quid, there was a winking quo. For every itching back, there was one hand to scratch it and another opening its palm for the grease of this piece of legislation or that bit of government largesse.

In addition to corruption, social frivolity gave the impression that Washington’s politicians were only competent in assembling a fashionable guest list. The capital’s denizens “lead a hard and troublesome life,” an observer said with tongue in cheek. After all, President Monroe and his cabinet “entertain strangers . . . in a very laborious way.” Here was a place where “society is the business of life” and where “people have nothing but one another to amuse themselves with; and as it is thus obviously for every man’s interest to be agreeable, you may be sure very few fail.” Americans could not see how this differed from a European court with powdered ladies and mincing men.

“So much bowing—so much simpering—so much smiling—so much grinning,” muttered Attorney General William Wirt. “Such fawning, flattering, duplicity, hypocrisy.” It made Wirt’s head spin and his stomach turn. People in Washington took all the wrong things seriously, and even those who had no stomach for simpering smiles seemed to avoid them out of snobbery rather than refinement. “There will be a drawing room [reception] this evening, for the first time this season,” Massachusetts congressman Jonathan Russell sniffed, “but as it is vulgar to go [to] the first I shall of course stay at home.” Russell’s arch “of course” said it all.

Americans neither knew nor cared that attending a party at the wrong time was unsophisticated. They suspected, however, that people who did care about such things did not care about anything else. A visitor watched Congress only briefly before concluding that Washington was full “of jackasses who are searching after immortal glory.” Elaborate procedures, endless and digressive debates, points of order, and yielding the floor to “my friend” (who was often a bitter enemy) made it all appear shallow and mindless. The government seemed intent on avoiding important business. “Such things cannot fail to make us very ridiculous abroad,” an informed citizen reported, more in sadness than in anger. “They weaken the attachments that ought to prevail at home,” he sighed. “The people at large are getting heartily tired of this abuse of the representative systems.”

Understanding “the people at large” is key to appreciating the vigorous reaction against Washington DC as a remote, defective machine, indifferent, unresponsive, and corrupt. It was those Americans who yearned for a return of civic virtue and selfless public service who saw Andrew Jackson as an American Hercules. He alone had the resolve and vision for the formidable task of cleaning Washington’s Augean Stables. True, others were more prominent politically, but that was to Jackson’s advantage because voters were disgusted by celebrated politicians who talked incessantly and then made things worse. Jackson’s military triumphs, however, were shining deeds. The Pennsylvania cowherd pulling udders a couple of hours before sunrise, the Alabama yeoman harnessing his plow by the pink light of dawn, the Louisiana boatman hauling his lines, the mechanic in Charleston, the laborer in New York—men like these all across the country did not know it was uncouth to go to the first party of the season, but they did know something about paying bills and keeping promises. Their eyes lit up at the sound of Andrew Jackson’s name.

At the same time, these ordinary Americans were gaining the means to become an irresistible electoral force. The American Revolution had planted the seeds for surging democracy, but the politics of deference had stifled them until the early 1820s, when citizens’ demands for more political participation became impossible to ignore and difficult to suppress. As states gradually extended voting rights, the politics of deference became a shabby artifact. Ordinary people would no longer cede governance to their social betters supposedly blessed with superior wisdom. Americans dismissed the idea that the only men qualified to run the government were those with the mysterious “talents” implied by membership in the ruling class. Whether occupying county, state, congressional, or even a presidential office, the high-born were judged as nothing more than highfalutin.

It became the foundation for a new political movement that was as simple as it was irresistible. In time, the movement would acquire important-sounding labels and be described as defining an era. At its outset, though, the people in it were ordinary Americans with a straightforward goal. They were certain that Andrew Jackson would go to a party if invited, no matter when it was held. They intended to throw him one.