Luther Baldwin was an ordinary man, but nine words he uttered in jest one July afternoon in a New Jersey tavern made him famous. Baldwin and a couple of friends were sipping on pints as a cheering crowd lined Trenton’s streets to watch John and Abigail Adams pass through town. Bells rang, and a cannon loaded with powder and wadding fired some harmless reports while the President’s carriage rattled down Broad Street. Inspired by the noise, one of Baldwin’s companions blurted out, “There goes the President, and they are firing at his arse!” Baldwin exclaimed, “I don’t care if they fired through his arse!”

Those nine words were likely the funniest thing Luther Baldwin ever said. It was not quite Falstaff, but it was typical talk for taverns in late eighteenth-century America. All in good fun, as they say. At least until someone gets arrested. For this was the summer of 1798, and Luther Baldwin was about to find himself in a great deal of trouble. So were the two unlucky barflies with him, one of whom had apparently said nothing and thus had done nothing wrong, apart from being in the company of someone who had violated federal law by opening his mouth.

It didn’t matter to a vigilant government whose cabinet secretaries spent their nights combing newspapers for potential prosecutions. In a few weeks, a grand jury indicted Baldwin and friends for uttering “seditious words to defame the President of the United States.”

Baldwin stood trial before Supreme Court Justice Bushrod Washington (George Washington’s nephew) the following spring. Baldwin was convicted and fined $150, a fortune for a fellow who made his living at the helm of a Passaic River garbage scow. Baldwin didn’t have the money and was thrown in jail until he could come up with it, which is to say he was thrown in jail, period.

The law that landed Luther Baldwin in a New Jersey prison was the Sedition Act of 1798. We might pause here to note that it was a mere fifteen years after the American Revolution that the United States Congress passed legislation to lock up citizens for speaking their minds. As incredible as that seems, more incredible was the President who signed it and committed the executive branch to its enforcement. Federal courts likewise agreed to hear cases and pass judgment on people for exercising a right protected explicitly by the Constitution. More than two dozen Americans had their freedom of speech quashed in the two years that followed. It was for brazenly political purposes.

Despite the emergency that purportedly justified the law, it was meant to silence dissent. Luther Baldwin was not a criminal. He was an example, a cautionary tale in the flesh, a man in lockup for making a joke, or more accurately, the wrong kind of joke.

The Constitution was supposed to protect free speech, but men who should have known better cynically nullified its protections. During the American Revolution, John Adams as Patriot embraced the right of free speech, and many who sat in Congress had taken extraordinary risks to secure it. In 1798, Congress seemingly forgot the reason for the risks, and John Adams as President lost his appreciation for the right to criticize the government.

Nobody gives up his freedom for a bad cause, which is how a presumed national emergency can rationalize foul policies. In 1798, Americans were told they faced a crisis. The United States was clashing with France on the high seas, a direct result of the war between revolutionary France and Great Britain. When the French demanded bribes as a condition for negotiation, Congress prepared for war. Exercising control over presumably “disloyal” citizens at home was one of the first orders of business.

In the summer of 1798, Congress passed, and President Adams signed into law a measure to prevent domestic subversion, which they defined as opposing the policies of the majority Federalist Party. The Sedition Act was odious in every way. Under it, anyone who dared to “write, print, utter, or publish . . . any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress . . . or the President of the United States” was committing a high misdemeanor punishable by fine, imprisonment, or both. Under this broad construction, the law altered the essential tradition of American (and English) jurisprudence by giving its enforcers the power to make what they found distasteful illegal.

Thomas Jefferson called what followed “the reign of witches” with good reason. After targeting the boozy Baldwin, the government went after bigger game. William Duane, the editor of the Philadelphia Aurora, was charged for supporting Republicans in the election of 1800. When the Northumberland Gazette in Pennsylvania said that John Adams was an enemy of liberty, its editor Thomas Cooper received a six-month sentence and a $400 fine. In New York, William Durrell fared slightly better (four months and $50) because he had merely reprinted an “offensive” article in his Mount Pleasant Register.

Newspaper editors were not the only prey. David Brown and friends raised a liberty pole in Dedham, Massachusetts, with messages such as wishing for the defeat of tyrants, the peaceful retirement of Adams, and that “moral virtue be the basis of civil government.” Hauling David Brown into court was disgraceful enough because his actions only emulated America’s revolutionary patriots in word and deed. Still, the severity of his sentence was shocking—a whopping $400 fine and almost two years in jail. Worse, Brown refused to name the people who had helped him put up the liberty pole, and for that bit of cheeky resistance, John Adams refused to let Brown out of prison even after the presumed threat to “national security” had long passed.

Persecuting newspaper scribblers and latter-day Sons of Liberty was bad enough, but the victimization of Matthew Lyon exposed the law’s real and darkest purpose. During debates over the sedition bill, Lyon, the Republican representative for Vermont’s 1st District, predicted that it could be used to punish members of Congress who disagreed with the President. Federalists scoffed at the claim. They pledged that as long as the President’s opponents did not lie, no magistrate could molest them, and no court would convict them.

Federalists, however, despised Matthew Lyon for his sharp criticisms of the Adams administration. In February 1798, Federalist Roger Griswold disparaged Lyon’s Revolutionary War service, causing Lyon to spit on him, and a violent confrontation ensued. Lyon’s friends dubbed him “the Spitting Lyon,” but Federalists exacted revenge as soon as they could wield the Sedition Act.

In the off-year election for Lyon’s congressional seat, Federalists in and beyond Vermont condemned him in newspapers for endangering the republic. The provocative charge that Lyon was a disloyal subversive was a cynical tactic to bait a touchy man. And it worked. He responded that he could not support Adams because “every consideration of the public welfare [is] swallowed up in a continual grasp for power, in an unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, or selfish avarice.”

Those words have an eerie pertinence today, so take heed. In 1798, they became the first count in Lyon’s indictment, handed down just weeks before the election, charging him with defaming the President to incite sedition.

Ensuing events were worthy of a Franz Kafka novel. Lyon lived on the Vermont frontier, a place happily devoid of lawyers, which was cheerful until you needed one. Incredibly, Lyon had to hire his political opponent to represent him. At his trial, Lyon insisted that a man’s opinion was beyond the reach of any law. He declared that any law that said otherwise was unconstitutional. The judge told Lyon to shut up and instructed the jury to ignore what he had said. The jury obeyed the order and took one hour to find Lyon guilty. The judge promptly sentenced him to four months in jail. He also had to pay court costs and $1000 in fines. The government then tossed Matthew Lyon into an unheated cell during the freezing Vermont winter.

They could lock up Matthew Lyon, but they could not shut him up. He continued his campaign for Congress from jail and won reelection with a more significant majority than two years earlier. His constituents petitioned President Adams for a pardon, but Adams sniffed that Lyon had not personally asked for it nor expressed remorse for his actions. The government kept him in prison for his entire sentence. After it ended, and when Vermont journalist Anthony Haswell celebrated Lyon’s release, he too was thrown in jail for sedition, the latest victim of a country made wretched by the reign of witches.

Historians who defend Adams, Congress, and the courts point to the low number of prosecutions as proof that no actual harm happened. Yet, was the persecution of twenty-five men under a disgusting law evidence of tolerable restraint? The government made certain men criminals to make others compliant.

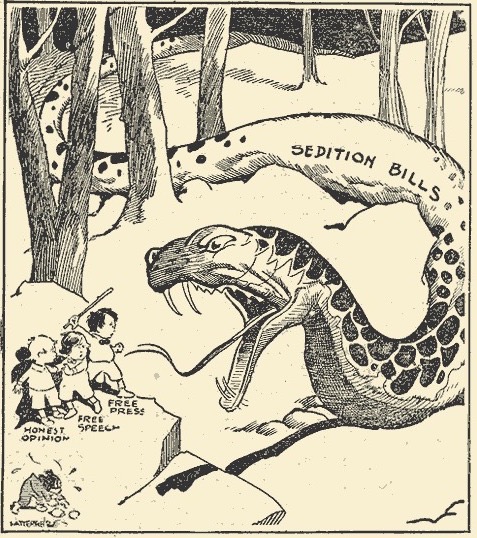

The quest for political supremacy always becomes vicious when a government outlaws speech. A century after the Adams administration locked up people for saying disagreeable things, Woodrow Wilson used the “national emergency” caused by World War I to throw dissenters into jail. He, Congress, and the courts teamed up in 1918 to use their own Sedition Act to prosecute Americans for criticizing the government with “abusive language.” The method was vile, the standard subjective, and the purpose political.

And now, we have this: a former president calls for curbs on speech that supposedly “misleads” or “misinforms;” American universities establish speech codes to muzzle debate and quash expression under the guise of barring “hate speech;” outlets outlaw words that are deemed “offensive.” And the current administration sets up a bureau in the Department of Homeland Security to ferret out “disinformation.”

Despite insistence that nothing sinister is afoot, in reality, financial ruin and dungeons are ultimately the tools for the ugly business of policing how people talk. Algorithms that monitor the internet for “unacceptable” speech serve dark masters, and a government bureau to suppress dissent while pretending to promote “national security” and “protect our democracy” is hideous.

Americans should be outraged, but they should also be fearful of complacency. In 1798, too many people who had lived through the American Revolution did not find sedition trials repellant. Will Americans be more vigilant about their liberties now? After all, the government these days keeps people in jail without bothering to try them at all, which is hardly an improvement over 1798 and promises worse to come. Nobody seems to care.

As our current authoritarians enforce their opinions, they employ the justification used by all autocrats over the ages: “We are doing this because we must.” But what they’re doing draws on the creed of witches stirring cauldrons, whether in ancient or modern times: “Because we can, we will.”

And something wicked this way comes.