George Washington did not sign the Declaration of Independence because he was not in Philadelphia during the summer of 1776. As commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, he was in New York trying to prepare that army, such as it was, for the British attack on the city.

He knew informally about the move for independence, one he quietly supported, but he was mindful that a proper sense of his place precluded his commenting on political questions. Nevertheless, he was heartened to hear from friends about the decisive measures taken on July 2 and 4 in the Continental Congress.

But not until July 9 did Washington receive John Hancock’s letter of three days earlier, a message officially informing him about the proclamation ending American allegiance to King George III. “Congress,” wrote Hancock in his opening sentence, “for some Time past have had their Attention occupied by one of the most interesting and important Subjects that could possibly come before them or any other Assembly of Men.”

Had the interesting and important subject been less sobering, the understatement might have been amusing. As it was, it was deadly serious. Hancock’s letter came with a thick bundle of printed versions of the Declaration of Independence. Washington was to use these to inform the army what the fight was now about.

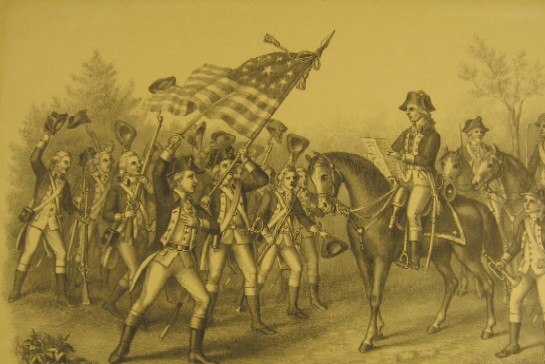

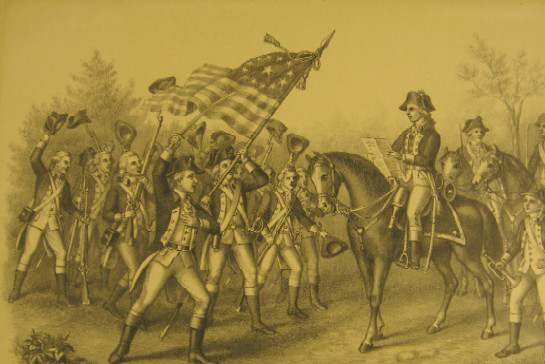

The general immediately instructed his Adjutant General to insert an announcement into the General Orders for July 9, 1776. The army was to hear the entire document read and thus understand the “duty, policy and necessity” that had moved Congress to adopt this grave measure. The brigades of the army were to form at 6:00 that evening at their respective encampments and hear the reading of the Declaration “with an audible voice.”

Junior officers spent the rest of the day seeing that soldiers were neatly attired for the ceremony. Before the appointed hour with muskets shouldered and bayonets fixed, brigades marched in ranks to their parade grounds. As the men stood in silent assembly, they watched the westering July sun cast lengthening shadows. Other than the birds chirping in trees, there were only the sounds of the soft clink of metal and the squeak of leather, always the background noise of armed soldiers trying to stay quiet. Then in the front of each brigade, the words were bellowed: “When in the course of human events. . . .”

As the words rolled on, some remembered trying to swallow but finding themselves dry. Others felt their hair move on their arms and scalps. The farm boys, the mechanics, the bank clerks, the shop keepers strained to hear the words. It was to be, after all, their fight — their fight for their country.

George Washington knew the manner of doing a thing could be just as important as the purpose for doing it. The men styling themselves the Continental Army were more an army in name than reality, but he had insisted they act like an army when it came to discipline, order, and ceremony. He had learned that these were not just trappings but were indispensable for an effective fighting force. His instructors in this matter had been the best on earth, professional British officers, whom he served under during the French and Indian War. They had been stern teachers, but he had not been the best pupil.

Washington might have thought of all that, for he was introspective by nature but extremely private about the process. Guilt over the past was impractical and wasteful for a practical man, pragmatic but also rigidly principled. The words of the Declaration might have dried his swallows and raised his hair too, especially when recalling the strange coincidence that his hardest military lesson had happened twenty-one years earlier on the very date, July 9, that he was announcing Independence to his army. And in a strange way that a George Washington could never have imagined, the events of July 9, 1755, were deeply intertwined with July 9, 1776, and what lay ahead for him and his country.

It happened when George Washington was only a half-baked lad. In the 1750s, French interlopers out of Canada began encroaching on the western parts of the British colonies. The Ohio Country of western Pennsylvania and Virginia was largely unsettled and thus open to adventurers. Before long, French soldiers were traipsing around this Ohio Country, building forts, and putting out markers of ownership. Virginia’s colonial militia tried to discourage the French, but they proved stubborn. The militia then tried to dislodge them. Colonel George Washington, a brash 20-something with more dash than sense, led this effort in a disastrous campaign that ended with his defeat. It also started a world war. Europe called it The Seven Years War. In America, it was the French and Indian War. Young Colonel Washington nearly sat it out.

At the outset of hostilities, Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie had to cope with not only George Washington’s disaster but with George Washington. The young colonel was touchy about criticisms of his botched campaign, and he cheekily complained about the inferior status of colonial militia officers, like himself, to their counterparts in the British army. When pouting won him no points, he huffily resigned his commission. It should have been the end of his military career.

Meanwhile, Dinwiddie bluntly informed London that only British regulars under professional officers could oust the French from their principal Ohio outpost, Fort Duquesne (at the site of present Pittsburgh). Accordingly, Britain sent a general officer to command Redcoats drawn from posts in New York and South Carolina, confident that this team would quickly teach the pesky French a thing or two.

The general was Edward Braddock, who landed in Virginia and inspired great confidence among the locals. It’s hard to see why. Braddock at sixty had become the nursery rhyme teapot — short and stout, with jowls thrown in for good measure. He also turned out to be surprisingly dull-witted, even for a minor major-general. The only flash of humor ever credited to him was when he spoke to a black servant girl named Penny. “You are only a penny now,” Braddock told her as he was departing for the campaign in the Ohio wilderness, “but I hope on my return you will be tuppence ” It was later marked as Braddock’s “only saying that is remembered.” Sadly, this was not altogether true.

Edward Braddock spent his life in the army, as his father had, but he never distinguished himself, which was how he wound up in a colonial backwater to shoo away a small French garrison in the middle of nowhere. Even by the measure of that lowly task, Braddock was an odd man for the job. He spent forty-five years in uniform but never saw much combat. Peaceful garrison postings slowed his rise, stalling him at lieutenant colonel as his contemporaries advanced in rank. Only recently promoted to colonel, he vaulted to his major generalcy not long before he sat down with colonial governors in Alexandria, Virginia, to plan his march into the American wilderness. Braddock knew absolutely nothing about the American wilderness.

Braddock at least knew how to act like a general. He barked brusque commands at subordinates for topographical information and logistical plans, but much of this turned out to be an empty act. Both Braddock and his subordinates were casual about their task, convinced that bumbling colonials had not been up to a job that professionals would complete without breaking a sweat.

That attitude could only take the army so far, though, and as the start of the campaign loomed, Braddock’s cocky staff began to exasperate him. He began noticing George Washington, a lanky young Virginian who seemed to know something about the place where Braddock was taking his army. He would never admit it, but the country was much bigger than he had imagined, and the enormous distance of a march across forbidding terrain troubled him, so he offered Washington a place on his staff. Washington accepted, but only as a volunteer, a peevish gesture because he was still smarting over his status. Braddock’s officers understandably resented Washington as an upstart.

The enterprise was ill-starred by these discontents and more. As the column prepared to trudge into the wilderness, its plans looked fine on a map, but they worried Washington.

Even its impressive precision crossing of the Monongahela River could not disguise that this professional army had many things wrong with it. As it wandered into the canopied forests of the Ohio River Valley, Braddock was unfocused and lazy. The army’s discipline frayed, and its hygiene lapsed. Dysentery soon culled the ranks and even put Washington out of commission until Braddock recommended a remedy called “Dr. James’s Powder,” which Washington proclaimed as the finest medicine in the world when it partially restored him.

Washington restored to a margin of good health was a mixed blessing, however. His fears that Braddock’s sluggish pace would allow the French to reinforce Fort Duquesne caused a faster march, but it exposed advanced parties to ambush. Soon after the Monongahela crossing, about nine miles from Duquesne, the French and their Indian allies pounced.

The fight called the Battle of the Monongahela is more widely known as “Braddock’s Defeat,” a disaster from its start. It began as a shock assault with a hidden but noisy attack that panicked the forward British units. The Indians’ ferocity decided the event in its first few minutes, but the ordeal that followed was lengthy and lethal, lasting for hours as the slaughter played out in slow motion. Officers fell dead or wounded, clusters of frightened soldiers endured repeated assaults and sniping, and many understandably ran for their lives. Braddock came riding quickly to the fight and was for once admirably decisive and sure. Washington was with him, and Braddock immediately sent him to bring reinforcements.

Washington was still weak from his illness and barely able to stay in the saddle, but he pounded through the woods, a big target for Indian snipers who shot two horses out from under him and sent at least four other bullets harmlessly through his clothes.

At the battle, Braddock was trying to restore order when a bullet pierced his chest. He crumpled to the ground but continued to command. He remained conscious long enough to direct a retreat to relative safety. The French and the Indians did not pursue.

Edward Braddock died on the night of July 13, 1755. His last words, ones remembered by the young Virginian, were a poignant observation: “We shall better know how to deal with them another time.”

Everybody in authority was either dead or down, and it fell to George Washington to command the retreat after Braddock’s death. First, he buried Braddock in an unmarked grave in the road that still bears his name. When dazed British officers objected to Washington deliberately marching their retreat over the grave, he tersely explained doing so would hide it. The officers looked down when the colonial told them: His body will be desecrated if found.

In the aftermath, the lessons of Braddock’s campaign were forever etched in Washington’s mind. He was the best provincial officer Braddock had ever met, but Washington had never commanded more than a gaggle of hunters and backwoodsmen armed with squirrel guns and fowling pieces. His only combat had ended with his surrender. Yet over the months of contemplation after the debacle on the Monongahela, Washington realized that Braddock had faced three enemies more formidable and unforgiving than the French and their Indian allies.

Ignorance, not the French soldier, was Braddock’s most indomitable foe. He knew nothing about fighting in the backwoods of colonial America. Second to ignorance was stubbornness, more lethal than the most ferocious Indian. Braddock remained convinced that his way of waging war, the one developed in Europe over the centuries and honed in recent decades by experience, was flawless and would be successful in any setting.

And finally, the last of Braddock’s enemies was indolence. Reconnaissance was slipshod when it occurred, and vigilance waned in the face of overconfidence. Here were Braddock’s greatest lessons for young Washington: learn, listen, watch. By his example of neglecting them, Braddock could not have been a better teacher in driving home those watchwords. He evidently sensed this himself at the end, summing them up in his final pronouncement: “We shall better know another time.”

Edward Braddock never had the second chance of another time.

Twenty-one years later, on the anniversary of Braddock’s Defeat, George Washington listened to the booming voices reading the reasons for this new war, his new country’s war. He knew the Royal Navy was bringing a British army, and he could only hope that this time, another time, his time, he would know better how to deal with them.